The anti-smoking campaigns of Europe

Published on

Translation by:

Melisa Laura DíazIn 2015 it is forbidden to smoke in public places in almost every European country and campaigns against smoking are being heavily promoted, yet their implementations and prohibitions vary in strictness and effectiveness, even from a communicative point of view.

In Italy, the Government has just approved new legislation on the subject. Among other things, smoking is now off limits even in your own car if you are carrying children or pregnant women, and dissuasive images displaying the damage caused by smoking will be introduced on cigarette packaging, (to be printed on at least 65% of the pack).

French advertisement by the director Yvan Attal (2010): the board—in suits and ties—asks how to get rid of toxic waste. The solution? To make people “swallow” it. “Arsenic, acetone, ammonia, DDT, polonium 210. Smoking is like ingesting the worst toxic products.”

But photos of clogged arteries and lungs are already a reality in France and in Spain. Beyond the simple “smoking kills” (“fumar mata” in Spanish, “fumer tue” in French), there are more subtle phrases like “Fumer peut entraîner une mort lente et douloureuse”(Smoking can cause a slow and painful death) and “Fumar provoca malformaciones en el feto” (Smoking causes deformations to a fetus in the womb). These rather shocking realities appear alongside other more conciliatory messages like “Votre médecin ou votre pharmacien peuvent vous aider à arrêter de fumer” (your doctor or pharmacist can help you stop smoking). Is this the “carrot and stick” strategy in action?

A more suggestive logic

Ironically, we find more suggestive phrases and seemingly more relaxed local government measures in Germany, a country with traditionally stricter regulation. The message “Rauchen kann tödlich sein” which is printed on the German tobacco is statistically correct, but conveys more of a sense that “smoking can be deadly”. Of course, it's true that you never know what will happen, but our Polish editor tells us, amazed, that only last year she saw a large billboard advertising Marlboro posted on the streets of Cologne.

German advertisement: to the question “What's wrong, baby?” The girl replies: “I see dead people”.

But even in Germany things should soon change due to an alignment with European standards. “Shock pictures” and stronger messages carrying emotional impact will soon be on every tobacco product sold in the European Union. An example in German: “Höre auf zu rauchen. Bleibe am Leben für Deine Angehörigen” (Stop smoking, stay alive for your loved ones).

Think of the children!

Poland is not far behind, here messages have a similar tone, shifting the focus from oneself to others: “Rzuć palenie, masz dla kogo żyć. Zadzwoń pod nr telefonu 0 801 108 108” (Stop smoking, you have people to live for. Call 0 801 108 108) and “Dzieci palaczy często idą w ślady rodziców” (Smokers' children often follow the example of their parents). Poland will also introduce dissuasive images in 2016.

English advertisement: “If you could see the damage, you'd stop” (Telegraph).

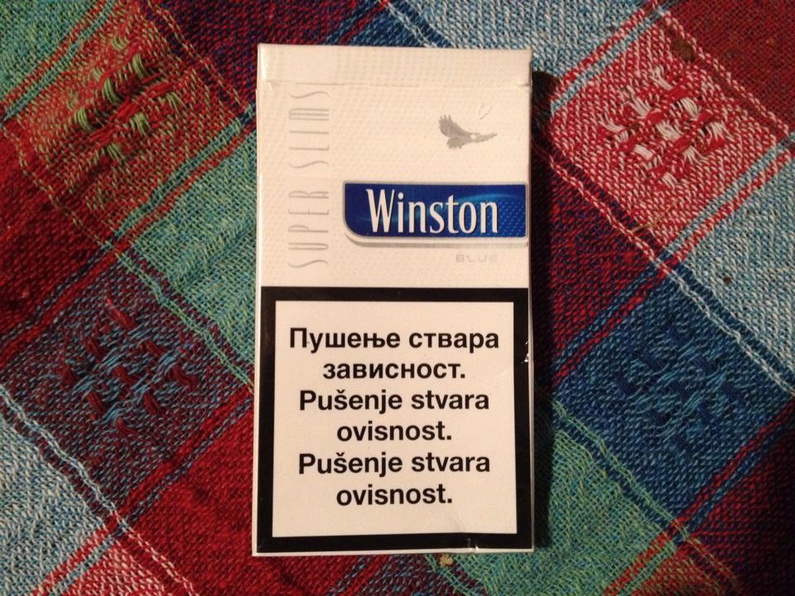

Outside of our EU comfort zone, we find a country that certainly doesn't skimp on ink to print these warnings on cigarette packs. In Bosnia and Herzegovina, the messages regarding tobacco mirror the political-administrative divisions present within the country. There are three official languages in the country, event though reference is made to their common roots, the language once called Serbo-Croatian. The message, "smoking is addictive," is featured in three languages. In Bosnian it says “Pušenje stvara ovisnost”, in Croatian “Pušenje stvara ovisnost”, and in Serbian it is written with a different script (although it is read in the same way) “пушење ствара зависност”. This triple cautionary tale may seem to be as superfluous as it is ineffective.

How effective is the anti-smoking communication?

Measuring the effectiveness of certain dissuasion campaigns is a difficult task. Sure, as the semiologist Giovanna Cosenza writes, “it is better to tell a young man that smoking could make him impotent today, than threaten him with cancer or other diseases tomorrow—inevitably people feel like this is something that will affect others, never themselves.”

Italian advertisement (2015): the last campaign of the Ministry of Health compared those not wearing helmets with those who smoke: They are both “dumb”, says the slogan. There is perplexity in the testimony of a person who, with a red circus jacket, is designed reach a young and often distant audience.

The problems of efficacy arise with the sterilised nature of the warnings (“they are only anonymous testimonies”) or their repetitive nature (“they are always the same messages”). In this case, it is possible that no language or verbal communication is worthwhile. “Honestly, when I was a kid, I paid absolutely no attention to the messages," says our French editor, Matthieu, "we almost laughed at it.”

In France and in other countries the “neutral packaging approach” has also been discussed: It would bind companies to produce tobacco and cigarette packages without logo or brand. As of yet it hasn't amounted to anything (possibly due to the protests from manufacturers and retailers).

One thing is certain: “I have started to find the printed images perhaps a little distasteful: they may be dissuasive, but to me they're especially disturbing photos, extreme, to the limits of belief, and perhaps because of this they are perceived as too distant," Matthieu continues, "in order to stop seeing them, it's not the case that I stopped smoking. I just bought a nice leather tobacco holder.”

---

This article is part of our Tower of Babel series, looking at the vagaries of European languages.

Translated from Le campagne contro il fumo in Europa