The 1, 000 Euros a month club

Published on

Europe’s youth follow the cog: university, a first job, building a future. But Seville’s brood of ‘1000-Euro-a-month-ers’ are finding even that hard

Are you aged between 22 to 40, highly qualified, university-educated, have a masters degree and speak other languages? Wanna earn 1000 Euros (£650) a month? You can in the hot southern Spanish city of Seville.

Take Elena García, 28. Armed with a History degree, masters and three languages, she can only find a temporary contract in a call centre paying around 800 Euros (£500) per month. Similarly, newlywed Juan Salvador, 32, is a TV editor who earn 1300 (£850) gross per month on a temporary contract. Both are part of the ‘mileurista’ generation who struggle to find permanent jobs worthy of their qualifications and paying more than 1000 Euros, despite the Spanish government’s recent reform to subsidise companies and change temporary contracts into permanent.

A life less costly

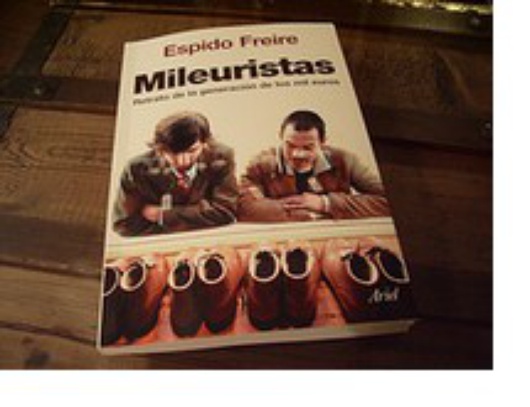

The term ‘mileuristas’ (literally ‘1000-Euro-a-month-ers or Euro-ists') was coined and entered current argot after a letter entitled Soy mileurista ('I'm a mileurista'), was written to social democrat daily El País at the end of 2005. Its author was Carolina Alguacil, a graduate working in advertising in Barcelona, disgruntled that she still couldn't earn more than 1000 Euros at 27. Two years on the discussion has spawned various articles and even a book by Espido Freire, entitled 'Mileuristas.'

The term ‘mileuristas’ (literally ‘1000-Euro-a-month-ers or Euro-ists') was coined and entered current argot after a letter entitled Soy mileurista ('I'm a mileurista'), was written to social democrat daily El País at the end of 2005. Its author was Carolina Alguacil, a graduate working in advertising in Barcelona, disgruntled that she still couldn't earn more than 1000 Euros at 27. Two years on the discussion has spawned various articles and even a book by Espido Freire, entitled 'Mileuristas.'

'My 1,500 Euros (£1, 000) gross salary isn’t the issue,’ says Manuel Guerrero, a 27-year-old journalist. ‘Accommodation prices are daylight robbery.' No surprise - a two-bedroom flat in Seville costs around 600-700 Euros a month, whilst 'mileuristas' only just make the minimum wage of around 600 Euros. They can’t refuse jobs for the pay, ‘as there are hundreds of others who are willing to do it for even less.’ Add to this the immense immigration to Spain (4.5 - 5 million in less than 10 years), where people often highly qualified themselves are willing to work for much less.

Rising house prices also mean young people are forced to stay at home longer, many until their mid-thirties - or marriage. ‘We are going back to the 15th century, with marriages of convenience being the only way to afford leaving home,’ says Guerrero. ‘The state is breaking a basic right of the Spanish Constitution – the right to decent housing.’

The phenomenon hasn't done anything to slow down Spain's ageing population, with over 41% of the population over 65 and one of the lowest fertility rates in Europe, with 1.34 in 2005. Those who do leave home don't have enough to fend for themselves, and they can't do everything they want to. ‘If I go on holiday it's to our families or the beach as it is cheaper,' says David Garrido, 28.

A degree for all widens the gap

Spain simply has too many well-trained young people in ratio to the number of well-paid jobs around. As in the whole of Europe, the post-war period saw a baby boom in Spain, which, however, lasted a decade longer than the other countries, until the end of the seventies. As the population increased, it became increasingly clear that Spain had one of the lowest literacy rates in Europe, with 8.5% of the population illiterate in 1970.

Spain simply has too many well-trained young people in ratio to the number of well-paid jobs around. As in the whole of Europe, the post-war period saw a baby boom in Spain, which, however, lasted a decade longer than the other countries, until the end of the seventies. As the population increased, it became increasingly clear that Spain had one of the lowest literacy rates in Europe, with 8.5% of the population illiterate in 1970.

It became about quantity, not quality when the government injected huge amounts into the education system to counter this. The number of people at university in Spain is the same as in Germany (around 1.4 million), but with only half of the population (Spain: 45 million, Germany ca. 82 million.). ‘In the eighties and late nineties, high unemployment meant university provided a sort of parking slot for families to leave their children,’ recalls professor Juan J. Dolado, from the Universidad Carlos III de Madrid Economics department.

Work shy

Meanwhile, as more unmotivated and perhaps not very academically-minded young people went to university, the vocational training system became ‘weak in comparison to countries like Germany. These people might have been wonderful mechanics or so, but now we have a Catch-22 situation.’ Things are changing a little, says Augustín Fleta González, another lecturer at the University of Seville. ‘The government would like to limit the number of people at university to achieve excellence, but I don't agree. I'd prefer to have a well-educated population who are more critical and mature. The key is to provide more vocational training.’

Added to low wages, it's easier to fire people on temporary contracts. Plus, severance payments are much lower; out of every 100 contracts signed each day, only 12-13 are permanent. All of this is demotivating, and people don't see any why they should work hard. Dolado points out Spain’s low productivity problem as a result. Salvador is bitter: ‘the policy of businesses is to earn as much money as possible through the workers, rather than having a faithful workforce who could contribute to the company in the future.’ ‘The business world is very closed and exclusive,’ adds Fleta González. ‘If things are changing, it is very slowly.’

Deflooding the market

The consensus seems to be that in a way, the 'mileuristas' are expecting too much, albeit through no real fault of their own. ‘Many subjects have a huge excess of students, such as law and many of the arts. The market has been flooded,’ says Dolado. People need to have more or different qualifications to those they already have. ‘The best things to retrain in are IT, communication and improving foreign languages. Spain is one of the European countries with the lowest knowledge of languages.’

On the other hand, youth unemployment is much lower than it used to be (in the mid-nineties almost 40%, and now 14% in total). ‘We need to have different politics, different awareness tactics towards work, salaries and sacrifices made,’ says David Garrido. ‘We need to do something to change the situation. We are all guilty in our own way.’

Two years on from the birth of the 'mileuristas', Salvador remains positive and wants to start a business in the near future. And though Guerrero has friends abroad in a better situation, he doesn’t want to leave. 'You have to solve the problem, not avoid it.’

In-text photos: Espido Freire's book was published in 2006 (Pgreta y doraimon/ Flickr), 'Mileuristas' demonstrate for higher salaries (vitojph/ Flickr)