"Thanato-technologies": messages from the afterlife

Published on

Translation by:

Maria-Christina DoulamiLaura is 56 years old. Until 2011, she ran a bar. She did not use a computer and did not have a Facebook account. Today, she doesn’t own the bar anymore; she sold it. She has learned to use the computer and the first thing she does in the morning is turn on her laptop, place it on the kitchen table and enter her login and password. Laura is a mother. Giulia, her daughter, died five years ago.

The conquest of immortality is the ultimate goal of entrepreneur Dmitry Itskov who presented last June, during the Global Future 2045 International Congress of New York, his project “Avatar”, a sci-fi plan that aims to liberate humanity from the ultimate limits of death, through an integration of biology, technology and human consciousness.

A bold border that reflects the inherent human need to investigate life beyond one’s own final experience or, at least, the unavoidable and painful confrontation with it.

Italians may vaguely recall the reflections of poet Ugo Foscolo on man's destiny after death in Dei Sepolcri. According to most of these poems, the tomb was the site of memory, the size of the greeting, the portion of the stone before which one kneeled. Today, these exact geographical coordinates are replaced by a new form of grief, a different mourning whose rapid evolution creates fears and raises questions that are difficult to answer.

The socialisation of mourning

Analysed from every possible perspective, the internet is the social context in which we move. The generation of digital natives will tomorrow give way to that of the ultra-digital natives who in turn will become super-digital, who will then become hyper, arch and so on, in an ascending climax at the end of which the relationship with the other will appear deformed in every aspect. Through these channels we carry out meetings, affections and practices, but the part that we start exploring today for the first time is that relating to the use of these spaces as forms of participation that interlink with the experience of loss.

Pages that come alive

Laura opened a Facebook account a few days after the funeral. A friend told her that through this channel she could see her daughter’s photos, read her posts and comments, her final status updates: she may paradoxically feel closer to her. Meanwhile, one of Giulia’s classmates created a private group, where, under the name of “Always and forever in the same side we will be”, friends, relatives, colleagues and classmates all connected. Laura feels less alone now, there are many who are close to her. Slowly, as time passed, however, she started to feel unable to do without this. It turned into a dangerous addiction, which became an impediment if she had to dedicate every possible minute to it and to running the bar at the same time as many other activities.

These two pages, together with Giulia’s personal and private accounts, are the spaces where Laura works every day, where she writes addressing her daughter, where she fights back the awareness related to this loss. It is a form of de-socialisation of mourning; it is the virtual cemetery where “thanatology” becomes “thanatotechnology”.

It has been a year and on 9 May 2011, Laura found on her account an unexpected notification. Facebook – always punctual – reminds her that it is the birthday of her daughter, “Write on Giulia’s wall!” That message can not be disabled. Giulia is gone but her account is alive and growing, and is being updated. Her presence is felt. Like the tingling at the end of an amputated limb, like the schizophrenic movements of the severed tail of a lizard. It is an extension of Giulia; it is the interface where “the live connected” associate with the “dead connected”.

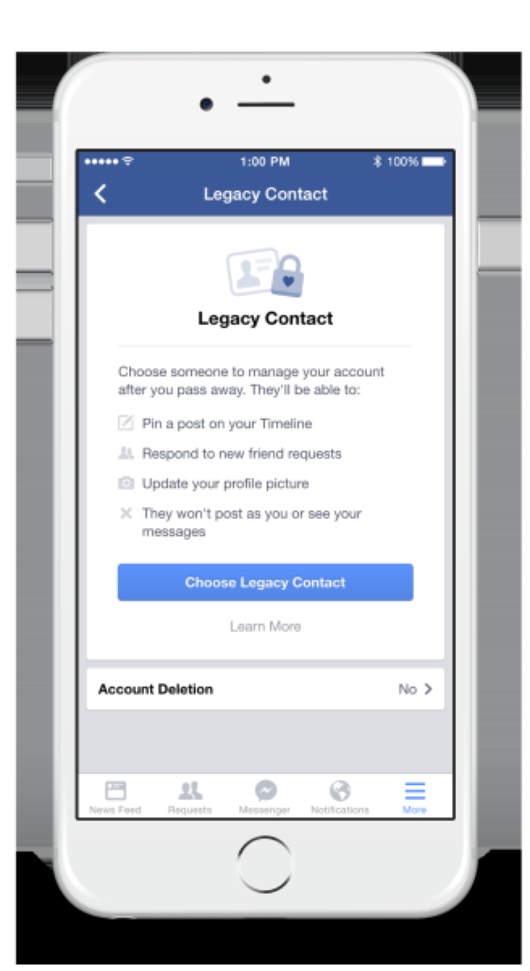

The regulatory gap and the right to be forgotten

On Facebook there are about 3 million accounts of missing persons. Finally, on 12 April 2015, Zuckerberg’s company introduced a new feature that allows users to select a contact, a family member or friend who can legally manage their account when they pass on to the after-life. “Once someone reports the death of a person – the website says – a “commemorative account” will be activated and the designated contact can write a farewell message to be displayed at the top of the board, respond to friend requests, update the profile picture or hide any photos. The contact will, however, not be able to log-in or read private messages.” One area still lagging behind from a regulatory point of view is that concerning digital heritage, defined as the set of data that the user has uploaded online, his/her intellectual property. Who should take charge of this information? The problem becomes crucial when conflicts are created between members of the same family. If the widow wanted to delete the account of the husband and the mother-in-law did not want to part with it, they might consider solving the issue by applying the criteria governing the transfer of inheritance, as required under Italian law. But what if the platform on which the data of the deceased is uploaded was in California?

On Facebook there are about 3 million accounts of missing persons. Finally, on 12 April 2015, Zuckerberg’s company introduced a new feature that allows users to select a contact, a family member or friend who can legally manage their account when they pass on to the after-life. “Once someone reports the death of a person – the website says – a “commemorative account” will be activated and the designated contact can write a farewell message to be displayed at the top of the board, respond to friend requests, update the profile picture or hide any photos. The contact will, however, not be able to log-in or read private messages.” One area still lagging behind from a regulatory point of view is that concerning digital heritage, defined as the set of data that the user has uploaded online, his/her intellectual property. Who should take charge of this information? The problem becomes crucial when conflicts are created between members of the same family. If the widow wanted to delete the account of the husband and the mother-in-law did not want to part with it, they might consider solving the issue by applying the criteria governing the transfer of inheritance, as required under Italian law. But what if the platform on which the data of the deceased is uploaded was in California?

Or in Ireland? Or in Switzerland? To what laws would one have to appeal? There are those who try to advance solutions, such as the localisation of Internet laws or the choice of a post-mortem representative for digital issues. However, for this series of questions there is still no clear answer.

How other social platforms are reacting

The problem does not only concern Facebook: each platform is adopting specific measures. Twitter automatically disables the account after six months of inactivity, LinkedIn only does this if someone reports the death of the user. Google has created the "inactive account management" function that allows users to share parts of their account data or to alert someone if they are not active for a certain period of time.

The problem does not only concern Facebook: each platform is adopting specific measures. Twitter automatically disables the account after six months of inactivity, LinkedIn only does this if someone reports the death of the user. Google has created the "inactive account management" function that allows users to share parts of their account data or to alert someone if they are not active for a certain period of time.

If the user dies, the person designated by him/her will receive an email like this:

Mario Rossi (mario.rossi@gmail.com) has asked Google to automatically send this message following discontinuation of the use of the account by Mario. Mario Rossi authorizes you to access the following account information:

+1

Blogger Gmail Picasa Web Album YouTube Download Mario’s data here. Best regards, Google.

Translated from "Tanato-tecnologie": messaggi dall'aldilà