Telejato: family-run, mini-CNN in Partinico, Sicily

Published on

Translation by:

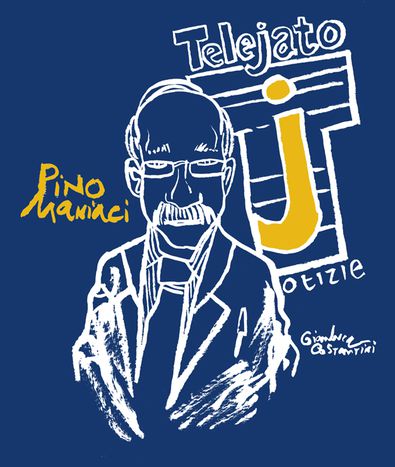

Annika ThorntonPino Maniaci has created a family business through his miniature version of CNN. The ‘longest news programme in the world’, with its 150, 000 viewers, is a mini-broadcaster fighting against the local mafia, the Cosa Nostra

‘Being truly anti-mafia is not about behaving like a victim of endless threats (the mafia don’t threaten, they shoot and then hide the evidence), but about being completely normal. You must live and write and have confidence in the state.’ That’s what art critic-cum-mayor Vittorio Sgarbi wrote in local Sicilian paper Giornale all’Indomani (‘The Day After’) of the recent mafia threats against Neapolitan writer Roberto Saviano, 29.

This is a state that for decades has abandoned the ‘journalists on the front line’. Those who have risked their own lives through their investigations, and what’s more, lost them to the mafia. This is a state that doesn’t allow justice even after death: such as in the case of the murder of Palermo-born journalist Mauro de Mauro, 49, who disappeared in 1970 after his investigation into a mafia-related death. The culprits who kidnapped him remain unknown today.

That the mafia should restrain themselves from killing is a fantasy from another time, because above all else they seek to escape the media clamour, and silence irritating and threatening voices. Since the seven journalists killed at mafia hands between the seventies and the eighties, there has only since been one case; that of the murder of Beppe Alfano, 48, in 1993. And if Roberto Saviano decides finally to leave his home country, the Camorra (the Neapolitan mafia) will have achieved its goal without firing a single shot. This does not mean that you should diminish the police force, but rather than it is really the job of the media to save the skin of certain troublesome journalists. Pino Maniaci is also no stranger to mafia threats, as a journalist and owner of local Sicilian TV network Telejato. He was the victim of an attack by the youngest son of a mafia boss, an agonizing fire in one of the station’s vehicles.

That the mafia should restrain themselves from killing is a fantasy from another time, because above all else they seek to escape the media clamour, and silence irritating and threatening voices. Since the seven journalists killed at mafia hands between the seventies and the eighties, there has only since been one case; that of the murder of Beppe Alfano, 48, in 1993. And if Roberto Saviano decides finally to leave his home country, the Camorra (the Neapolitan mafia) will have achieved its goal without firing a single shot. This does not mean that you should diminish the police force, but rather than it is really the job of the media to save the skin of certain troublesome journalists. Pino Maniaci is also no stranger to mafia threats, as a journalist and owner of local Sicilian TV network Telejato. He was the victim of an attack by the youngest son of a mafia boss, an agonizing fire in one of the station’s vehicles.

‘Microtv’ and ‘the big boss’

Telejato is a small network with its headquarters in Partinico, Sicily. Initially it was owned by the communist refoundation party (Partito Rifondazione Comunista, PRC). It was then taken over in 1999 – as a result of impending financial collapse – by the entrepreneur (who was by his own admission hardly successful), Pino Maniaci. Maniaci has encountered significant problems: firstly the hereditary debts from the previous management and the imposition of the classification of ‘community television’. Secondly, he was then being forced to produce the station himself with an advertising limit of three minutes per hour. But all of this did nothing to discourage him. Over time the idea came to turn Telejato into a kind of miniature, amateur CNN; journalism and judgment on his own nation. And so the ‘world’s longest TV news programme’ was born, with two hours of service from 2:30pm until 4:30pm, watched by nearly all of it target viewership; the 150, 000 people in twenty-five provinces of Palermo who are brought together by a single television signal from Partinico.

Among these people there are undoubtedly members of the mafia. Thanks to the coverage of the Maniaci family (his children Letizia, 24, and Giovanni support him, along with several collaborators spread around the region), they are kept up-to-date with the events of rival clans. Clan boss Bernardo Provenzano, known as the ‘the big boss’ – he was arrested in 2006 after more than forty years in hiding – was amongst the most regular of viewers of the Telejato news programme. The 75-year-old followed it from his safe house a few kilometers from the small town of Corleone. Pino Maniaci, interviewed over the phone, told us of how they would put out an annual call to the mafia: ‘In January we gave them our wishes for a happy new year and told them not to be a piece of s*** and to hand him over.’

Like in Iraq: in Italy, they shoot

It wasn’t only the mafia threats that put an end to the journalistic career of Pino Maniaci. You can also add legal action and allegations from politicians and businessmen alike to the mafia threats and attacks. More than 200 lawsuits have been launched from the Bertolino distillery alone, one of the largest in Europe, whose owners were annoyed by the investigation carried out by Telejato into pollution by its factory.

‘Italian journalism - from guard dog of democracy to chihuahua’

But all of this did not guarantee a financial return. ‘We were able to pay the television fees and buy a few paninis at the bar,’ explains Maniaci, but moreover because ‘journalism should be the guard dog of democracy, but has been reduced to a chihuahua.’

The only way of restoring this role is to talk about sensational topics without reticence. This makes the conspiracy of silence of the local and national press all the more embarrassing. Until not so long ago they were printing just a portion of the truth (for example, giving just the initials of mafia members). They were ‘discussing unimportant matters,’ Maniaci goes on to explain. ‘Today whilst we are forced to hide, even they talk now about the mafia.’

As it was for Leopold Dominique, the 63-year-old Haitian journalist fighting for his country’s freedom, his fight forever immortalised in the documentary he starred in himself, The Agronomist (2003) by Oscar-winning director Jonathan Demme. Thus follows the release of the documentary Telejato – the best TV in the world by the Franco-Italian 'Mon Amour Film' production society. Pino Maniaci cannot help but be cheered by this. ‘Its exposure is life-saving, here on the front line. In the town of Partinico in the space of one year, there have been seven killings, it’s like we’re in Iraq: they shoot you.’

Illustrations courtesy of Gianluca Costantini

Translated from Telejato: una televisione antimafia