Teach Me Talent

Published on

When dealing with the fact that many film directors have never gone through any academic cinema school, the issue is not to turn the question to the filmmakers, but to the teaching of art in general. If no one disputes that specific, exact sciences can - and should - be taught (could anyone understand all mathematical and physical domains with no guidance at all?

), art seems to have less determined codes. This question is not new, and it takes us back to the ancient discussion: are arts a matter of talent or a matter of skill?

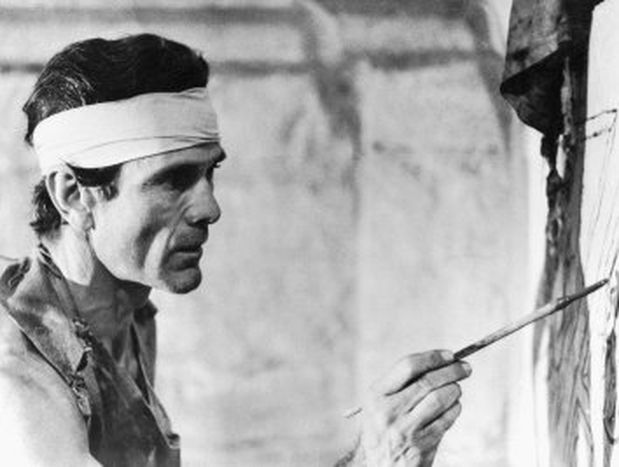

On one hand, we have powerful artistic figures such as self-taught genius Mozart. But then, the ideas of learning and creating are contradictory, the first coming from another individual, and the second coming from oneself. Painting illustrates this conflict the best, attributing value to the great masters and students of the XVII century, but according even more attention to those who seem to subvert the rules in their own. In art, reproduction has always been appreciated, but creation and invention carry a more powerful social status.

One of the reasons for this is the fact that humans highly appreciate what they cannot understand. Technique can be mapped out and summed up, but personal talent comes from a place we cannot identify. How are geniuses created? More importantly, how do we create those who can recognize them? The answer to the recognition of talent is highly complex and sociology still spends a lot of time trying to figure out how societies decide. For example, that Picasso is better than Braque, or Martin Scorsese is better than Brian de Palma.

The matter of talent in cinema gets more complicated when one thinks that it’s the art most connected to, and dependent on, technology. We can write books with only a pen and a piece of paper (or excrement and some walls, to think of Sade), but a movie can’t be made – for now, at least - with no machinery at all, whether it be a 35 mm camera or a cell phone.

In order to really separate those who operate machines from those who create for them, ancient critics used to separate “artisan” from “artist”, meaning, on one hand, the one who possesses a form of knowledge, and on the other hand, the one who possesses an inner talent. This dichotomy hasn’t changed much in contemporary art: film critics, especially the highly influential ones of the Cahiers du Cinéma in the 50s, separated “metteur en scène” from “auteur”, or author, the first term emphasizing the profession, and the other emphasizing the independent creation. Well-loved directors – let’s say, Hitchcock back then, or perhaps Gus Van Sant today – are given the precious label of authors, while others (Minnelli, Tornatore, Haneke, you pick) are called by terms related to the technical aspect of cinema: filmmakers, film directors, metteurs en scene. As usual, everything related to hands-on work is put on a lower level in comparison to the work of the mind – or the heart, the spirit or whatever we may call it.

For that reason, film schools seem able to teach only the less appreciated form of cinema: that of the work, of the technique and the history of art. It’s not surprising to see that icons directly out of cinema schools, such as Spielberg and Lucas, are directly related to the industry, the money, the technique (and therefore a lower form of art), while troubled selftaught geniuses like Pasolini and Kubrick are recognized as real inventors.

To sum up, what’s at stake here is an incompatibility between the romantic concept of cinema and the pragmatic, contemporary one. The question is not “can cinema be taught?”, but “can transmissible knowledge be recognized as art?” We are not close to an answer.

Article Bruno Carmelo, originally published in the September issue of Mas y Mas, NISI MASA's monthly newsletter