Swabian influx in Berlin ruffles regional feathers

Published on

Translation by:

Stuart WhittinghamIn recent years Berlin has seen a wave of migration from the affluent Schwabenland (Swabia) region in south-western Germany, but the welcome from native Berliners could hardly be described as warm. Does this raise doubts over the feasibility of free movement around Europe as a whole?

'Where on earth are you from?’ Inventing a watertight cover story is essential these days if you are going to use the Swabian vernacular in Berlin. Parochial language such as Fuddel, a Swabian term of endearment for a girlfriend, is certain to prompt some kind of cross-examination. Life in the German capital is tough right now for this small community. The Swabians, who are from a region west of Munich, are famous for their Spätzle, a type of soft egg noodle widely eaten in the region. They are commonly regarded as hard-working, clean and careful with their money. But some Berliners are less generous, accusing them of invading their city like a swarm of hungry locusts.

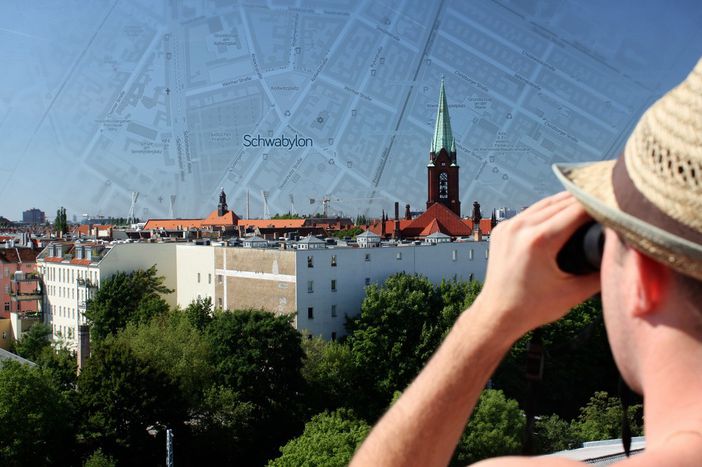

Swab-Berlin

The Swabians began to ‘arrive’ after reunification, drawn in by the allure of the wanton, thrilling, unconventional metropolis of Berlin. Most chose to take up residence in a run-down neighbourhood called Prenzlauer Berg, an area traditionally populated by pensioners, students, artists and blue collar workers. Houses and apartments were bought and renovated. Fashionable restaurants, boutiques, galleries and, more recently, frozen yoghurt bars sprung up to cater for the new arrivals. Before long, everyone was talking about the area’s trendy ‘scene’. The old residents quietly disappeared, along with their outdoor toilets and coal ovens. Well, OK, not all of them - there are still a few hardened souls who have stood firm against the onslaught of horrendous rents and babyccinos.

One of these few remaining Berliners in 'P-Berg' as the district is nicknamed is Wolfgang Thierse, the social-democratic vice-president of the bundestag (German parliament). Thierse has been vocal in his criticism of the influx of Swabians and the cultural changes they have brought. His most furious attack was aimed at the linguistic ‘Swabification’ of the area, citing bakeries who choose to market their bread rolls as Wecken, as in the south of the country, rather than using the traditional Berlin term Schrippen.

One of these few remaining Berliners in 'P-Berg' as the district is nicknamed is Wolfgang Thierse, the social-democratic vice-president of the bundestag (German parliament). Thierse has been vocal in his criticism of the influx of Swabians and the cultural changes they have brought. His most furious attack was aimed at the linguistic ‘Swabification’ of the area, citing bakeries who choose to market their bread rolls as Wecken, as in the south of the country, rather than using the traditional Berlin term Schrippen.

Thierse's comments initially prompted volleys of fierce criticism from the Schwabenland. Then Berlin’s Swabian community hit back with a mysterious nocturnal ‘Spätzle’ attack. Persons unknown threw a bowl of the Swabian national dish over the monument to Käthe Kollwitz, the sculptress who was hounded by the nazis and became an icon of the Berlin working classes. A group calling itself free Schwabylon claimed responsibility for the attack. In a statement, these noodle-armed urban guerrillas declared that they are fighting for the liberation of Prenzlauer Berg and for the establishment of a state called ‘Schwabylon’.

'Clash of identities'

The German press latched on to this absurd skirmish between Swabians and Berliners, quickly building it up into a clash of regional identities and hailing a new movement of local patriotism. There is nothing new in this meeting of different regional characteristics; Germany has always been a great federal melting pot. Sadly for the Swabians, however, they have now become synonymous with an ever-growing social divide in a city where rents are rising at a breathtaking rate, in stark contrast to earnings. This community is fast becoming the prime focus for the anger and resentment of everyone who fears being marginalised, despite their having a good education, being multilingual, having spent time abroad and being prepared to accept insecure employment conditions. Those are the ones who would take a pay cut and work reduced hours in order to help businesses through the financial crisis, or who no longer need to worry about inheritance and wealth taxes because they no longer have any inheritance or wealth. Perhaps unsurprisingly in such circumstances, visitors to Prenzlauer Berg find it hard to get excited about the area’s new image. The mood is similar to the fury seen during the German chancellor’s 2013 visits to Portugal and Greece. Of course, just like posters of Angela Merkel with a Hitler moustache and swastika, stickers proclaiming ‘Swabians Out!’ are disproportionate, irrational and deplorable.

This phenomenon highlights a far more widespread problem: the larger the social divide, whether in Berlin, Germany, Europe or globally, the more serious the threat to social cohesion. In such situations, people will cling more desperately to a particular identity. This may occur on a national level (southern Europeans uniting against the ‘nasty Germans’, or all Germans together against the ‘lazy Greeks’), regionally (Schwabylon, Flanders, Catalonia) or locally (a specific neighbourhood, locality, or even an individual tube stop).

Against this background, the idea of a common European identity seems to belong squarely in the realm of fantasy. It comes across as nothing more than the distant dream of a few enthusiastic students who emerged from an erasmus student exchange programme with some new friends in Rome, Krakow or Marseilles. For them, the idea of a common European identity is based on their own shared experiences. In principle, all Europeans can look back on shared experiences, on a common history that has often been somewhat less entertaining than an erasmus exchange semester or two.

'Berlin’s experience throws up tough questions about the future of the continent and about achieving a fairer society'

The eurozone crisis has made it yet more difficult to remember our common ground; in fact, it has driven an even greater wedge between the peoples of Europe and has re-opened old wounds. Berlin’s experience throws up tough questions about the future of the continent and about achieving a fairer society. A common European identity will only be able to take root in the hearts and minds of the people if it can provide a fairer society, improve mutual understanding and lead us to better appreciate the problems of others. It will come about if people can be passionate about a European society where they need have no fear of social deprivation and can live without jealousy and pre-conceptions. Then we will all be able to get along not only with our neighbours, but with their 'Fuddel' too.

Images: main (cc)flibflOb/ flickr; in-text © Free Schwabylon official facebook page

Translated from Schwabylon: Berliner Spätzle-Blues