Streetwork: Helping Kids in Krakow's Roughest Neighbourhood

Published on

Growing up is a complex matter in any part of the world. So what happens to those who come from troubled families, kids who cannot rely on their family and whose only guidance comes from the streets? In Krakow a team of professionally trained workers are showing young people that there is an alternative to life on the streets.

A tall, blonde teenage boy enters the room smiling shyly. He shakes hands with everyone, takes off his jacket, cap and backpack and drops them onto the couch. When asked about his school day he responds as many students would, ‘It was fine’.

We are nine miles from the centre of Krakow, in the offices of Streetwork located next to the Bienczycki market, in the Nowa Huta neighbourhood, acknowledged as the worst in the city. The name translates as ‘New Steel Mill’ and it was built in 1949 as a model city by the then communist government. However the huge tower blocks now house over 200, 000 people making it one of the most densely populated areas of Krakow. Outside the windows the trees are bare and ten-storey apartment blocks tower across the street. The door to the office is covered in posters of young people, residents of the area that the Streetwork project sets out to help. Inside it is bright and spacious, painted a warm green, an oasis of care and compassion in the middle of this difficult neighbourhood.

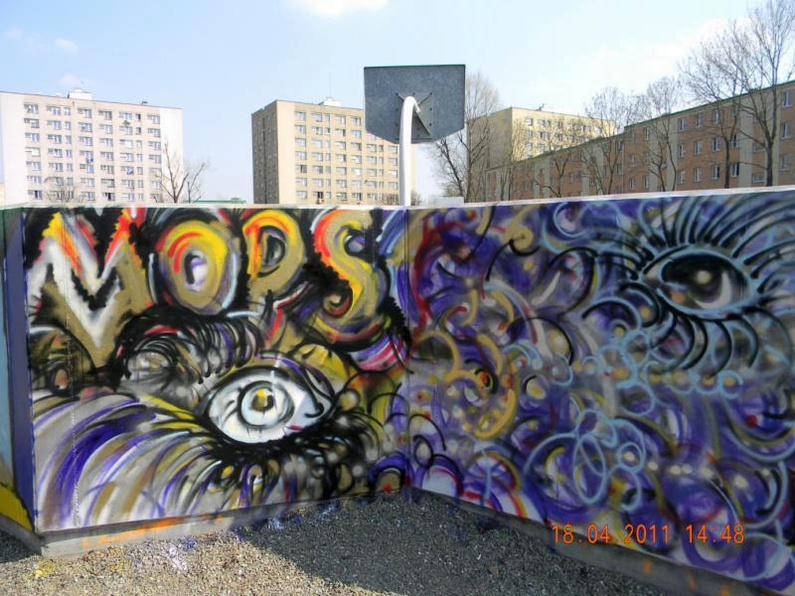

The project started in January 2012 and is open every weekday and some Saturdays to offer help and advice to young people aged 15-25 with the aim of motivating them to succeed at school, to graduate and to plan for their future. The project is divided into four units and this one, Team B, proudly display photographs of the many activities they offer the young people, including football matches, day trips and graffiti jams.

The project started in January 2012 and is open every weekday and some Saturdays to offer help and advice to young people aged 15-25 with the aim of motivating them to succeed at school, to graduate and to plan for their future. The project is divided into four units and this one, Team B, proudly display photographs of the many activities they offer the young people, including football matches, day trips and graffiti jams.

Shades of hope in the shadow of the blocks.

‘This is not a playroom’ explains Lukasz Kisiel, one of the streetworkers with the Nowa Huta project. ‘We have to go out onto the streets to find them. They can come here to do their homework, to learn, to get help writing their CV, drink tea or relax playing darts or table football’. There is also a psychologist available to listen to problems and give professional advice to the young people.

Three pairs of street workers each comprising a male and female member cover the area, concentrating on the most problematic spots – parks, playgrounds and the areas around grocery stores.

‘At the beginning nobody really knew where to look, so we had to do a survey of the district’ says Lukasz. ‘Our main target is not necessarily young people from poor families, because sometimes wealthier children have even bigger problems. They are not criminals yet, but they could eventually become so’, he adds.

Anyone can be an outsider.

The project started in 2001 with volunteers who would look for and help homeless people during the winter months. Five years later, after serious research on the problem and based on German experience they began to work with young people too. Lukasz Hobot was one of the first six street workers in Krakow and is now team co-ordinator for the project. He understands the problem in depth.

‘We had no exact data so we just started working in the neighbourhoods,’ he says, recalling the beginning of Streetwork. ‘Of course methods are changing, places are changing, and the people we are working with are changing too, but the main idea is the same’ he continues.

Krakow has a relatively young population with almost 13% aged 15-25, but this is not the main reason for the problems, as the project focuses on only 5 of the 18 districts of the city. During the years the project has been running it has received financial support from city funds, donations and NGOs but the most financial help has come from European Union funding, mainly from the European Social Fund.

‘The problem is to give these kids some kind of motivation, because they spend a lot of time on the streets,’ Hobot explains. ‘They have problems but this doesn’t mean they are bad. They create their own world and are afraid to get out. Streetworkers are the only people who can open their eyes. They need to find a balance. Everyone can be an outsider. You don’t have to be a member of an ethnic or cultural minority to be an outsider’.

‘The problem is to give these kids some kind of motivation, because they spend a lot of time on the streets,’ Hobot explains. ‘They have problems but this doesn’t mean they are bad. They create their own world and are afraid to get out. Streetworkers are the only people who can open their eyes. They need to find a balance. Everyone can be an outsider. You don’t have to be a member of an ethnic or cultural minority to be an outsider’.

Stimulating creativity and developing abilities

Streetworkers need exceptional social skills because making the first contact is difficult. Word of mouth is usually the best advert for the project. Even if young people are curious it is not easy to reach them and it is important for the workers to gain their trust. Most of the youngsters are stuck in their neighbourhood because they don’t know anything different or what else to do. Their daily life is difficult and they lose touch with life outside of it. To combat this they are encouraged to come up with ideas for group programs. The idea is to stimulate their creativity and develop abilities to show them that there is an alternative way of life to wasting time hanging around the local park.

One of the most recent activities was a climbing contest. The youngsters were challenged to organise into small teams instead of the ten to fifteen member groups more common on the streets. Streetwork also involves the parents in the project because supporting the whole family leads to better outcomes for the young people.

One of the most recent activities was a climbing contest. The youngsters were challenged to organise into small teams instead of the ten to fifteen member groups more common on the streets. Streetwork also involves the parents in the project because supporting the whole family leads to better outcomes for the young people.

Small victories against big problems

A survey by Streetwork amongst young people involved in the project shows that most of them face multiple problems in their daily life. 92.5% have behavioural problems; 85.7% have difficulties at school and almost the same percentage have problems in their family life too. Eight out of ten young people think they need to talk to a psychologist; seven out of ten have experienced problems with drugs, and more than half admitted having issues with group interaction.

Streetwork has already helped more than 600 young people improve their lives. They have shown these young people that there is an alternative to hanging round in the park all day getting drunk and becoming involved in anti- social behaviour and criminal activities. In fact it is hard to tell how many young Krakowians have seen their lives changed thanks to the advice of the staff at Streetwork. For this organisation every single positive change is a success to be proud of.

THIS ARTICLE IS PART OF A SPECIAL SERIES DEDICATED TO KRAKOW. IT'S PART OF "EUTOPIA: TIME TO VOTE", A PROJECT RUN BY CAFÉBABEL IN PARTNERSHIP WITH THE HIPPOCRÈNE FOUNDATION, THE EUROPEAN COMMISSION, THE MINISTRY OF FOREIGN AFFAIRS AND THE EVENS FOUNDATION.