Stefano Bartezzaghi: 'Europe is more like a crossword than a crossroads'

Published on

Translation by:

Fiona Herdman Smith

Fiona Herdman Smith

The Italian puzzle writer and word games expert, 45, explains his view of Europe as a crossword grid with myriad definitions

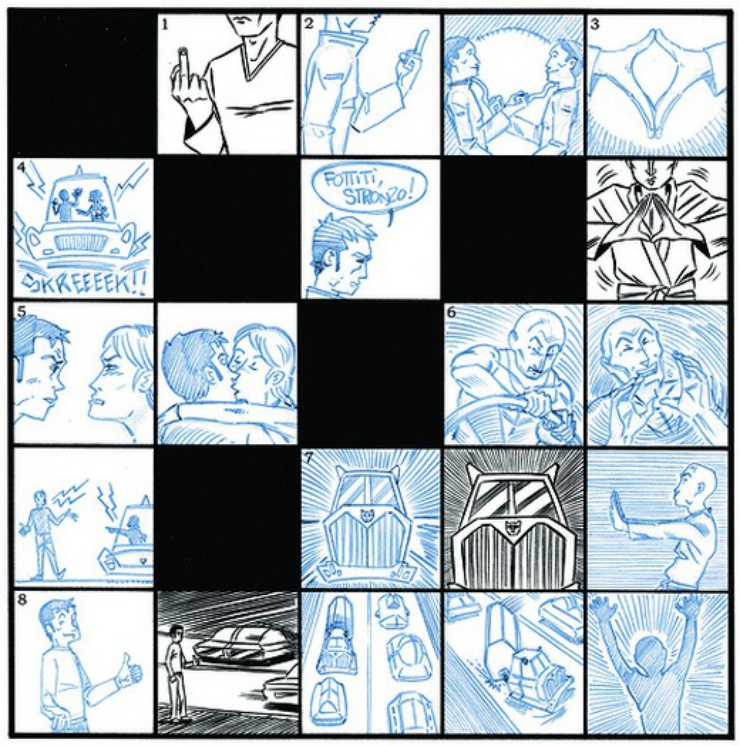

The metaphor is convincing and striking: Europe is a huge crossword, an immense grid of squares, complete with countless definitions. It contains the French Riviera and the Roma people, Scandinavian fjords and the great islands of the Mediterranean, the steppe and the ramblas, textbook Czech and Abruzzese dialects. 'Such a crossword should take all the major European schools into account, starting with the French school, but also Italian, English, Spanish, and so on,' begins Stefano Bartezzaghi.

'A History of Crosswords' is a splendid synthesis of a decade’s work in word games published in the Italian press

The Milanese graduated in 1962 with a degree in arts and entertainment, having written a thesis on the semiotic structure of games. He is now a big name in the Italian puzzle world and it’s no coincidence that he has just written A History of Crosswords, which is a splendid synthesis of a decade’s work in word games published throughout hundreds of pages of the Italian press, the most famous of which is Lessico e Nuvole ('Lexicon and Clouds'), which appears in Il Venerdì di Repubblic, the Italian newspaper's Friday magazine.

Puzzles? No, maps

Bartezzaghi’s view of Europe is unique, filtered as it is through that black and white grid which has become like a lens through which he sees the world. 'While I was studying the history of the crossword, I realised once again that enormous differences exist between European cultures. It’s not simply a question of language: there’s a huge gulf between the USA and the UK.' Bartezzaghi uses what other people would call a puzzle as a social map. 'You see, the crossword is successful because it can adapt. Of course there’s a linguistic component, but above all there is a cultural component – differences in sense of humour, different levels of literacy…all this is reflected in puzzles.' He denies that some languages are better adapted to puzzles than others in the absolute sense. Each language has its own idiosyncrasies: 'Italian and Spanish, for instance, are not great for homophones, but they are ideal for rebuses.'

Transpositions, please, not translations

The Oulipo (Ouvroir de Litérature Potentielle – Potential Literature Workshop) was founded by the French poet and novelist Raymond Queneau and is still active in Paris. They meet every first Thursday of the month at the Mitterand Library to find new outlets for their subtle games of homophony. Elsewhere, they have to make do as best they can. 'Italy has the Oplepo,' (Opificio di letteratura potenziale) but the mechanisms are completely different. 'By definition, a word game is something which cannot be translated: at most it can be transposed and what’s more, there are excellent examples of transposition. Italo Calvino and Umberto Eco’s work on Raymond Queneau, for example, is stylistically marvellous. And Vladimir Nabokov, who translated his own work, knew that the best foreign language versions of his work were beautiful but unfaithful.' Thus everyone must create their own games: 'Although speakers of word games have fun, there is no scale of values, no word game Olympics.'

Dialects, humour and ambitious definitions

Dialects would claim the same ontological dignity for themselves. 'Dialect is always linked to orality and it’s not a given that it will always be handed down through the generations. American slang, for example, uses a lot of rhymes. Puzzles, on the other hand, need written language: there are no crosswords in dialect, or at least none that have become successful,' continues my interlocutor, inscrutable behind his flamboyant glasses. Language and humour therefore remain inseparable, although it is difficult to say which came first: 'it’s like the chicken and egg: Tristan Bernard, who was originally a playwright, was the inventor of the witty definition, which is still part of the French crossword tradition today.' And yet everything goes back to an unlikely source: Gustave Flaubert. 'His Dictionary of Received Ideas paved the way for this style of definition.' It is no coincidence that, amongst the pages of the volume, we find the following definition: 'Only used to describe monuments.' What is it? ‘Erection’, of course.

'Only irony can define us'

As the conversation draws to a close, an opportunity arises which is too tempting to miss, at the risk of descending into banality. 'Mr Bartezzaghi, the clue for four across on my crossword is ‘Europe’. How would you define Europe?' The puzzle man suddenly looks very serious, deep in an almost religious silence of reflection, which I dare not interrupt with so much as a cough. Then, nervously putting pen to paper, with a faraway voice he hypothesises: 'My definition would play on the sense of union. De facto unions, some formal, others only in appearance…I would look for an ironic play on that. Because after all, only irony can define us, don’t you think?'

Translated from Stefano Bartezzaghi: l’Europa è un crocevia? «Piuttosto un cruciverba»