Société Réaliste: French-Hungarian duo on a ‘free’ European Green Card

Published on

Created in 2004, the anarchist artist duo are ‘part of a factory’ which only accepts Europe as an idea ‘if Japan is Europe, if Alaska is Europe.’ We learn how they deconstruct the constructed, introverted entity which they see as Europe in Paris

I’m fifteen minutes late, but my interviewees welcome me with a smile on their faces as I land on a chair in a café in the arty area of Paris. We first met a week ago when Ferenc Gróf, 36, and Jean-Baptiste Naudy, 26, participated in an art practices seminar at the Jeu de Paume museum of contemporary art in the Tuileries Gardens. Their work is constructed around the question of a sign in political structures, art production or economy. They perceive it on a non-national level, as ‘European cultural policy is nationalistic.’ They define themselves as French or Hungarian only when obliged. ‘In Austria it is easier to define ourselves as Hungarians,’ says Gróf with a twinkle in his eyes. A tall bald man with calm blue eyes, he represents the Magyar touch of the co-operative.

Art in a factory

The duo met when they planned to curate an exhibition examining if there was a correspondence between contemporary art and socialist realism, widely considered an error in the history of art. 'However, we came to the conclusion that by putting ideas to experimental practice - that is by doing art – we would be more capable of answering the question,’ elaborates Naudy, Gróf’s shorter, darker and compelling counterpart. Société Réaliste was born. The two artists are part of an artistic factory where the workers can be replaced. The term ‘co-operative’ is essential; the men appear as representatives of an entity, never as individual artists.

We don’t explain the past because it’s history. We don’t have our CVs on our website

But their international co-operative isn’t what you typically see in Parisian galleries. The art world of the capital is introverted; to have contacts you need to go through the art schools. With their background the reputation they have achieved is not self-evident. Naudy studied literature, art history, aesthetics and art production at Sorbonne university where he first met Grof, who studied medical and fine arts. The latter doesn’t want to elaborate though. ‘We don’t explain the past because it’s history.’ ‘We don’t have our CVs on our website,’ Naudy adds, ‘because biography is writing about one’s life and acts. A factory can’t have a life.’

European but nationalistic art world

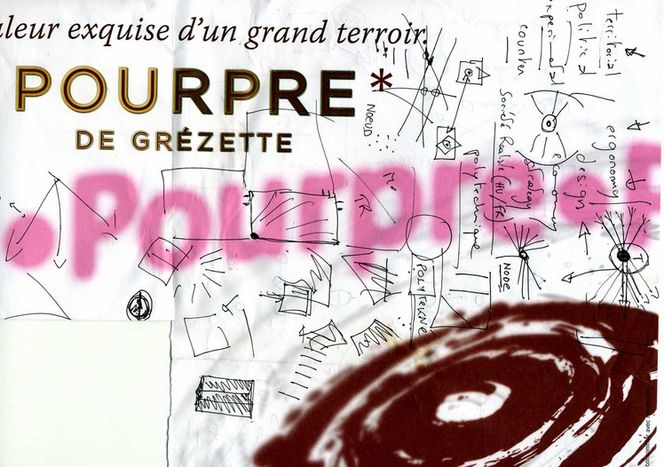

We stroll around the exhibition openings in the galleries of the Marais district, which seems to be the art centre of Paris, as I learn that Société Réaliste’s process of creating ideas is based on dialogue. ‘We produce signs and objects which can be used to fabricate representations,’ Naudy says, having doodled abstract figures on a paper already replete with his visual explanations. ‘We ask how to move from a thought to an image and vice versa.’

One of these objects is their website on which an immigrant can apply for a European green card. The ‘EU green card lottery project’ resembles the ‘parasite’ websites that try to mimic the American green card lottery system, in order to exploit migrant workers hoping to go to the USA. The website is so realistic that Société Réaliste received around 15, 000 replies. ‘We are interested in the way the European Union tries to construct itself, for instance through immigration; it doesn’t have an international immigration policy, it is still national. But how can countries like Finland, Italy, Slovakia or Ireland have a common policy to handle the question? Who or what is a foreigner in Europe?’ Naudy lists energetically.

Of the European art world, Naudy cites three artistic centres: commercial London with its English artists and big galleries, non-commercial Berlin with artists from all over Europe and ‘false’ Paris, which lives from its glorious past with the aid of French art school artists. ‘Even in Berlin everyone lives from their own national funding - Norwegians pays Norwegians artists, and so on.’

The only idea that has productive value is cosmopolitanism

So what could be the ideal Europe? ‘It is difficult to imagine Europe without all the other parts of the world,’ Gróf answers. ‘Why not construct a global entity?’ Naudy fills in. ‘For us, the only idea that has productive value is cosmopolitanism.’ The two evidently believe in a dialogue which shouldn't be restricted to any ideological or geographical area. ‘We both come from an anarchistic school that is against state, political and economical institutions,’ says Naudy. ‘I accept the idea of Europe if Japan is Europe and if Alaska is Europe,’ finishes Naudy.