Social entrepreneurs, social media: how to innovate in Istanbul

Published on

In Turkey, the third largest country on facebook, words like 'blonde' are banned in domain names, and after midnight, its twitter streams flow with 2.0 sonnets of love. The country is on the cusp of a paradigm shift. Young changemakers in Istanbul are using these limited online tools to offer fresh ideas for an offline society, which is flailing under limited freedom of speech

The aroma of fish market stalls in Karaköy leads to the waterfront, where the waiter regrets there is no Turkish coffee to optimise the sensational view of the Golden Horn. 'It's not visionary,' laughs advertising student Engin Önder, 20. He is a member of Istanbul's institute of creative minds ('Yaratici Fikirler Enstitusu', ICM), a group of twenty-somethings behind the network of creative professionals which ‘brought social media outdoors' two weeks prior. Their citizen journalism offshoot '140journos' beamed a live twitter debate, #notonuclearenergy versus #yestonuclearenergy, directly onto a famous monument, the Galata tower. It marked an indelible use of Istanbul's streets; the location for crushed protests under the country' broad terrorism laws became a renewed public forum for debate through social media on 30 June.

#Massacre media: test the limits

'Tahrir was a big wake up call for everyone,’ says journalist Ahu Ozyurt, who moderated the debate below Galata. We go over the news headlines from a roof terrace near the central Taksim square: the editor at Topkapi palace; child brides; a professor released from prison; the prime minister; no sign of the Kurdish protests. Turkish journalists openly exercise self-censorship to avoid being fired, fined or imprisoned. Ozyurt, a blogger at the independent news site Gazeteport.com, believes this is a generational phenomenon limited to mainstream media. The situation could change if citizens like social media’s entrepreneurs ‘test the limits a bit more’ - especially in Turkey, where 50% of the 75 million-strong population are under thirty.

In Karaköy, Önder expertly dodges the waves crashing against the banks which spill by our feet now and again. 'We have the power to generate real-time newsworthy content live. Let's do it in public spaces where voices are not heard, and lighten journalism,' says Engin. Launched in 2010, the experimental group are pushing their ideas forward away from the confines of the mushrooming university entrepeneur classes. Önder, Safa Soydan and Oğulcan Ekiz developed ICM whilst live blogging from conferences over the Arab Spring during university in the US. The media's mute approach to the massacre in the mainly Kurdish township of Uludere in December 2011 was in stark opposition to the twitter storm they followed from Washington.

Mainstream self-censorship can extend to social media too. ‘In Turkey social media went from being quite celebrity-oriented to quite political, but you still can’t really retweet Kurdish news,’ adds Ahu, who says not being able to report on the Uludere massacre a ‘watershed for Turkish media’. ‘We discovered the news on twitter at 4am; the official statement came at 8pm. 34 people had died. It was the turning point for twitter. The government started to pay attention. But social media also brings us back to the coffee shop debate. I don’t believe that the government wants to censor it (though in August 2012, rumours spread that the government is planning to block twitter and facebook ‘at certain times’ - ed). People look to twitter for light-hearted things.'

Mainstream self-censorship can extend to social media too. ‘In Turkey social media went from being quite celebrity-oriented to quite political, but you still can’t really retweet Kurdish news,’ adds Ahu, who says not being able to report on the Uludere massacre a ‘watershed for Turkish media’. ‘We discovered the news on twitter at 4am; the official statement came at 8pm. 34 people had died. It was the turning point for twitter. The government started to pay attention. But social media also brings us back to the coffee shop debate. I don’t believe that the government wants to censor it (though in August 2012, rumours spread that the government is planning to block twitter and facebook ‘at certain times’ - ed). People look to twitter for light-hearted things.'

#Earthquake and community

In Cihangir, a neighbourhood by Taksim housing the arty and famous, twitter activist Guray Gursel links the rise of sales of smart phones in the country to growing activism via social media. As ‘Burus Vilis’, the bar musician-turned-social media ‘phenomenon’ presents a weekly radio spot on trending topics. The top three right now include #happybirthdayspongebob, #bigbanggroup, and #lookafteryourfreedom about the weekend’s ‘One Love’ music festival. Sponsored by the country’s only beer brand Efes, it is subject to an alcohol ban for the first time. This is the perfect paradoxical example of ‘offline’ Turkey today, and young Turkey’s online voice in it. Vilis illustrates twitter’s importance for ‘community’ by describing rescue operations organised and retweeted on the microblogging service during the Van earthquake in 2010, the same year that the iPad was relesed.

Turkey’s 25 million users thrive on bringing social media back to real communities, as the start-up zumbara neatly illustrates. Aysegul Guzel, 29, left her job as a consultant and employee of a major retail chain to implement the timebanking site in October 2010, inspired by the ‘bancos del tiempo’ in Barcelona where she lived. There is no Silicon Roundabout in Istanbul, but tonight we are with a dozen others at a Netsquared event, ‘using social technology to increase social change’. Empty Turkish tea cups line the windows looking on to the Bosphorus. 'Timebanking is more flexible than the barter economy as the cost of the service is in how much time it has taken,’ says Guzel. ‘I saw it lacked a social technology aspect.' In the south of Turkey, her grandmother understands her granddaughter’s time-not-money initiative as a 2.0 adaptation of the Turkish local ritual of ‘imejhe’; 80% of all Turkish start-ups are linked to Turkish culture, but Guzel admits that because she is working in alternative economy, her mission can often be dismissed as a hippy movement.

Turkey’s 25 million users thrive on bringing social media back to real communities, as the start-up zumbara neatly illustrates. Aysegul Guzel, 29, left her job as a consultant and employee of a major retail chain to implement the timebanking site in October 2010, inspired by the ‘bancos del tiempo’ in Barcelona where she lived. There is no Silicon Roundabout in Istanbul, but tonight we are with a dozen others at a Netsquared event, ‘using social technology to increase social change’. Empty Turkish tea cups line the windows looking on to the Bosphorus. 'Timebanking is more flexible than the barter economy as the cost of the service is in how much time it has taken,’ says Guzel. ‘I saw it lacked a social technology aspect.' In the south of Turkey, her grandmother understands her granddaughter’s time-not-money initiative as a 2.0 adaptation of the Turkish local ritual of ‘imejhe’; 80% of all Turkish start-ups are linked to Turkish culture, but Guzel admits that because she is working in alternative economy, her mission can often be dismissed as a hippy movement.

‘There is a mistrust towards social volunteering. It is seen as revolutionary,’ agrees Matthias Scheffelmeier, 28, country coordinator for the global network of social entrepreneurs on Ashoka Turkey. Its changemakerxchange platform connects entrepreneurs including Guzel and helps them use social media and other tools to develop and spread solutions to problems they see in society.

‘There is a mistrust towards social volunteering; it is seen as revolutionary’

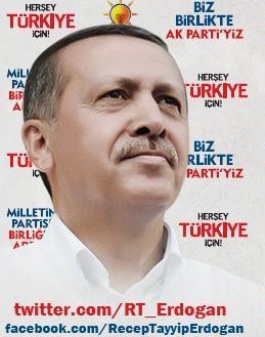

As ‘journos’, Önder and co. have spent 2012 instagramming or tweeting audio interviews from Hrant Dink's assassination anniversary, to the ongoing court case against Oda TV. Despite their efforts illuminating the bugbears of prime minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan - a man who, Ahu Ozyurt has reported, has accused Istanbul's festival-going youth of 'rampant immorality' - they will work with his office on a gastro-tourism application. 'People take photos of food the world over, but Turkish food is neglected,' says Önder, as we head to the boys' favourite street vendor for a chickpea, rice and kidney bean plate, washed down with Ayran. I'm invited along to Starbucks, so that the boys can recharge the various electrical appliances whose batteries died during our chat. Turkey's youth were largely apolitical after the military coup in the 1980s (and the third in the country’s short history). Today, they are the peers of the over 100 journalists and 700 (mostly Kurdish) students behind bars, armed with smartphones, tablets and ideas.

This article is part of the fifth edition of cafebabel.com’s flagship project of 2012, the sequel to ‘Orient Express Reporter’, sending Balkan journalists to EU cities and vice versa for a mutual pendulum of insight. A huge thanks to Burcu Baykurt and Derya Kaya

Images: main © courtesy of yaraticifikirlerenstitusu.com; in-text © NS