Smuggling cigarettes in Schengen Slovakia

Published on

Translation by:

louise bongiovanni

louise bongiovanni

Since December 21 2007, border controls have vanished inside the EU. The eastern border now seems like a fortress - what's 'big brother' in Slovak?

Jacky is the hero of the evening. The retriever from Slovak customs sniffed out a stash of cigarettes in a Ukrainian Opel. The car driver has to take his car apart under the eyes of the customs and border officials. Without a word he unscrews parts. Cigarettes everywhere, waiting to be found in every possible nook and cranny. More than 20 cartons. The driver could face up to three years in prison and a driving ban of five years.

Everyday life on the Vysne Nemecke Slovak-Ukraine border. But the cigarette smugglers are only 'small fish'. With massive help from the EU, Slovakia has made its eastern border impervious to unwanted migrants. The border crossing is the last control point between Ukraine and the Atlantic Ocean since the extension of the Schengen zone on December 21 2007.

Schengen miracle

Miroslav Uchnar, the chief of the brand new police headquarters in the otherwise sleepy town of Sobrance in eastern Slovakia, speaks of a 'small miracle'. A year before, the EU seemed to have decided to remove Slovakia from the Schengen-extension. The Czechs, who had the freedom of movement of their citizens right at the top of the agenda, threatened to close their borders with Slovakia. And this, even though the Czechs and Slovaks had lived together in the same state for nearly three quarters of a century and since their split in 1993 maintained a relaxed border regime.

Robert Kalinak, the Slovak Minister for the Interior, thinks back to this time with horror too, when the Slovaks with their inadequate preparations for Schengen caused frowns from Brussels to Prague. Now, the mid-thirty year old raises proud cheers, 'As my colleague from Luxembourg toured the border, he erected a border fence and told journalists, I'm now standing on the Luxembourg-Ukraine border. I can't praise him enough.' With visible amusement, he pushes the mouse on his desk. It controls a large monitor, which conjures up live images from the almost 100 kilometre border to Bratislava.

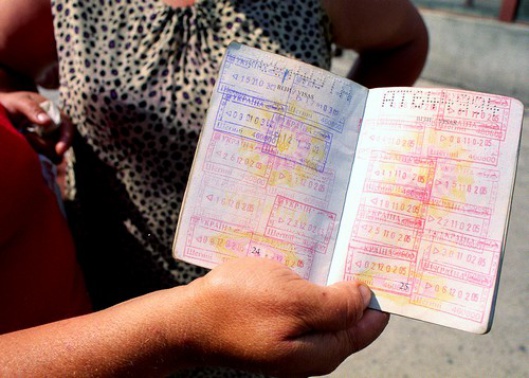

Poland-Ukraine border (Photo: Jan Zappner/ n-ost.de)

Poland-Ukraine border (Photo: Jan Zappner/ n-ost.de)

To show migrants and their smugglers, Kalinak has to revert to old video recordings. 'We don't have any current cases,' he says almost apologetically. 'The word has spread that we've put up a fortress here. Immigrants now try to get to the west through Hungary and Poland instead.'

Kalinak is thankful for the 'solidarity of the Europeans.' They raised a third of the 100 million euros to be invested in strengthening the border. 'In addition, specialists in car theft and passport forgeries came to train our people. You can now rightly call the border European.'

Cameras wherever you look

In the Sobrance command centre everything goes along calmly. Six operators sit in a small room, where all of the images from the border run at the same time. It's a border without barbed wire, spring guns or minefields. Cameras and mobile films make sure that no-one can easily get into the Schengen area. In the southern section of the border, which is flat and even, there are cameras with only a 186 metre gap between them. In the dark or in bad weather, they work automatically with infrared.

The geography of the craggily mountainous northern section is more difficult. There, special surveillance apparatus impede illegal immigration. The so-called thermo-vision apparatus can see up to 5 kilometres away. They are a Slovak invention and can differentiate between humans and animals. 'No-one would believe that it worked,' remembers chief of police Uchnar, 'until we demonstrated it with a police officer. He showed up on the camera, but his dog didn't.'

'Big brother' is at the lorry and train crossings too: lorries are scanned. Every person who hides in them becomes a prize for technology. There is no chance here either for people on the way to EU-paradise. If they manage to slip through, they still risk being caught in several zones up to 40 kilometres inside the country.

Last stop: Sobrance

In the police station refugees are not only questioned, but also cared for. 'We've had shocking cases,' says police chief Uchnar. 'For example, the completely exhausted and confused woman from Chechnya, who we found in a wood on the Polish-Ukrainian border zone. She left Chechnya with her four children but was found with one - the other three were died from cold and starvation and she had to leave them behind. They hadn't been able to survive the strain of the escape.' A doctor will soon open up a practice on-site.

Those who don't make an application for asylum to Slovakia, will be deported to the Ukraine. 'Co-operation with the other side runs without a hitch,' extols Uchnar. Certainly there are exceptions. Ukrainian customs officials repeatedly aid traffickers and smugglers. So that nothing happens on the Slovak side, customs officials there get their hard lives financially sweetened.

On average people earn 378 euros a month in eastern Slovakia. Customs officials, whose number has been boosted from 240 in 2004 to now 886, get the equivalent of 840 euros. 'That should take away the temptation to allow oneself to be bribed by immigrants or smugglers,' explains Uchnar. Of course the officials know 'big brother' the best. And they know that their colleagues would never pass something up.

The author is a member of the German writer correspondant network n-ost

In-text photo: (Jan Zappner/ n-ost.de)

Translated from 'Big Brother' auf Slowakisch