Slovenian journalist: death threats after arms trade trilogy

Published on

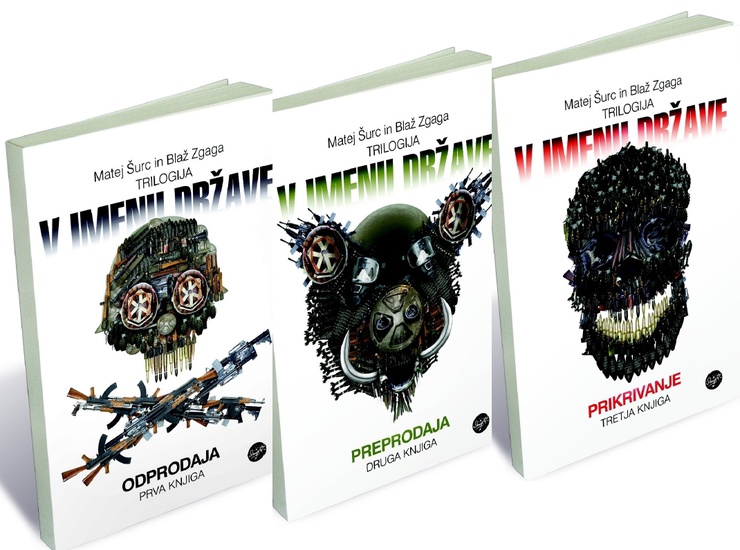

In Slovenia, a trilogy published between summer 2011 and spring 2012 has exposed the secrets of the arms trade during the Balkans war and the role of the country's politicians in it. It's been an ache in the sides of those in power and with money and interests whom the book denounces. Co-writer Blaz Zgaga, 38, may be in hiding but he won't stay down

The two reporters behind In The Name Of The State, a trilogy on arms dealers in Slovenia which sees its final book Cover-Up out in spring 2012, have their work cut out. Is there an audience willing to know about their country's deeper role during the Yugoslav war between 1991-1995? 'Arms smuggling,' says co-writer Blaz Zgaga, 'is the mother of all scandals. We have combined hard facts to show the violations during the UN embargo. The Yugoslav war was not carried out by a little group, but co-ordinated by European countries.' He is looking after his daughter whilst we speak over skype. As she gurgles in the background, he launches into an enthusiastic, passionate and down-to-earth analysis of a story which has consumed him for the last four years.

Did you hear the one about the Croatian officer

Zgaga agrees that Slovenia's reputation is slightly whiter than cream. 'Slovenia was a success story, the role model small transitional country that the US and EU needed. It’s also a small, boring country where it is really difficult to attract international media attention when things go wrong. We chose the right moment to create a petition against censorship and political pressure on journalists in 2007, right before Slovenia’s presidency of the European council.’ Blaz shortly embarked on what seemed like an ‘impossible’ crusade with one of the 571 signatories of the petition, Matej Surc, an ex-radio correspondent in Belgrade and Washington who had reported 'live from the Bosnian battlefields'.

Zgaga agrees that Slovenia's reputation is slightly whiter than cream. 'Slovenia was a success story, the role model small transitional country that the US and EU needed. It’s also a small, boring country where it is really difficult to attract international media attention when things go wrong. We chose the right moment to create a petition against censorship and political pressure on journalists in 2007, right before Slovenia’s presidency of the European council.’ Blaz shortly embarked on what seemed like an ‘impossible’ crusade with one of the 571 signatories of the petition, Matej Surc, an ex-radio correspondent in Belgrade and Washington who had reported 'live from the Bosnian battlefields'.

In 2009 they marked a huge success after a freedom of information request allowed them to create four databases out of 6, 000 declassified documents from the interior and defence ministries, providing answers to such questions as ‘How does a Croatian officer cross the border with 3 million DM and pay for military weapons'. Through a combination of 'encrypted emails and lots of car rides’ Zgaga and Surc worked in secret in the capital. Book one Sell, published in June 2011, focuses on the export of arms supplies of the former Yugoslav army confiscated during the war in Slovenia between 27 June and 7 July1991, the first conflict to affect them since the second world war. Book two Resell, released a couple of months later, had a more international angle, singling out arms export countries such as Bulgaria, Romania and Russia. The contents read like an espionage-fuelled action franchise: Vienna served as HQ whilst transactions were executed in Budapest to companies registered in Panama, with millions of dollars forwarded to Polish and Ukrainian (via its Odessa mafia) arms exporters.

Red bastards

Blaz admits he was demotivated at times. ‘It’s a tremendous project with many sleepless nights but my colleagues pushed me forward,’ he resumes. For someone who is forced to watch his back after receiving anonymous online death threats on 19 November, he sounds surprisingly jovial. 'There was a public call for our liquidation, that we should be choked in our blood,' he continues, before singling out his own sector as being first to attack. 'It was published on the propaganda media of a party. Even the editor-in-chief joked that we recognised ourselves as ‘red bastards’ with our pictures published by it. These are not journalists following the public interest; look at who owns the papers.' In the mid-noughties, his fellow journalists were replaced or censored because of political opposition reasons. ‘80% of editors were replaced; I had problems publishing my articles. I had a reputation as a problematic journalist because I am always asking questions,' he says of a 2000 house search during the Sava scandal, after revelations of a US intelligence operation in the Balkans. Zgaga's surname means heartburn - 'so troublemaker,’ adds Blaz.

Zgaga's troublemaking short career started when he was a 20-year-old sociology undergraduate who joined the left-liberal newspaper Delo before working his way up. ‘It was not my decision to go into investigative journalism: whenever I went deep enough, I always hit the same names. No-one is willing to confess that we did it. The activities of those corrupted elites which originated from those arms deals are still hidden. It’s one of the biggest obstacles of the region. Silence is the premium example of contempt.’ The hope in his mission lies in accountability and a chance for society to move forward. ‘At Kings College in London, war studies is offered as part of the humanities department, the arts!’ he offers by comparison. ‘Go to any bookstore in London or everywhere and you will find books on wars and revolutions under the ‘history’ section.'

Zgaga's troublemaking short career started when he was a 20-year-old sociology undergraduate who joined the left-liberal newspaper Delo before working his way up. ‘It was not my decision to go into investigative journalism: whenever I went deep enough, I always hit the same names. No-one is willing to confess that we did it. The activities of those corrupted elites which originated from those arms deals are still hidden. It’s one of the biggest obstacles of the region. Silence is the premium example of contempt.’ The hope in his mission lies in accountability and a chance for society to move forward. ‘At Kings College in London, war studies is offered as part of the humanities department, the arts!’ he offers by comparison. ‘Go to any bookstore in London or everywhere and you will find books on wars and revolutions under the ‘history’ section.'

In Slovenia it is the publishers Sanje (‘Dreams’) who have had the 'courage to publish such a book'. So can the trilogy have an impact on a country in the middle of changing hands, or on its youth? ‘Common sense is still alive in Slovenian people,’ says Zgaga, referring to the 4 December elections which saw Janez Jansa, an architect of the arms smuggling story, voted out of power in a surprise defeat for the right-wing. 'Usually young people aren’t interested in politics,' he adds, 'they’re too busy trying to survive. Though I am happiest when readers call me or I meet them and they say they understand. ' That's important seeing as now, Zgaga's Slovenia is 'boring again'.

Images courtesy of © Blaz Zgaga and Sanje publishing house