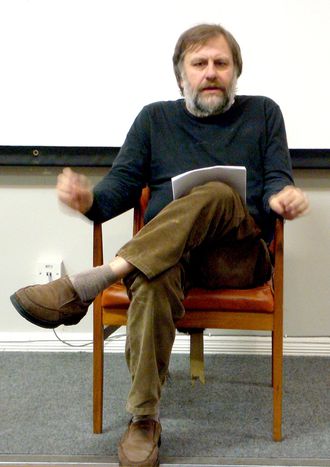

Slavoj Zizek: great European export or sell-out to US cultural hegemony?

Published on

The Slovenian philosopher cites Viagra to prop up Lacanian theory, wrote a critique of the matrix and has linked Hegel to sex games and Maggie Thatcher. Zizek is an impish theorist with immense transatlantic and popular appeal. So why haven't we heard of him?

Gaullists shook their heads in knowing despair at the accession states when six accession countries signed up to Uncle Tony's warcry in February (1). Then Chirac came over all big daddy, and scolded the errant children for playing with that forbidden toy - power. No doubt somewhere between Michigan and Ljubljana at that time, Slavoj Zizek was giving his own appraisal of the 'divided Europe' to an audience of the largely US faithful.

This article is an attempt to provide an idea of Zizek might have said or at least a sense of the politics and symbolic place occupied by a 'new' European export in an era of transatlantic rivalry and US cultural hegemony.

Ambassador European thought

Thanks to wit, hyperproductivity and a ferocious intellect Zizek has achieved the impossible. He is very much an ambassador of European thought, having brought a group of highly complex navel-gazers (including Lacan, Hegel and Kant) to the attention of the American collective unconscious. And how? His secret is accessibility and openness to popular culture as a valuable (and obscene) reference point for his more abstract work. Drawing from a complex web of Hegelian philosophy, Marxist dialectics and Lacanian psychoanalytic theory he spices up his interpretation of high theory with anecdotes from popular films and saucy jokes.

The result is so palatable to undergraduates that he now has a cult following among college kids in the United States as well as eastern Europe. So great is his grip on US popular culture that renowned postmodern identity theorists whose work he has rubbished queue up to sing his praises. The 54-year-old Slovenian philosopher, who was much unemployed during the communist era (due to his 'insufficiently Marxist' thesis), now has a steady job at Ljubljana university and international acclaim. He spends a semester a year in the United States and hates 'pseudo-intellectualism'. Meanwhile, in his native Slovenia, he is a national institution, at times criticised by left-wing intellectuals for being too close to the ruling party which he helped to found...

Critique of socialism to critique of consumer capitalism

Zizek's life story might be read as that of an intellectual seduced by American academia and the trappings of popular culture. However, as Zizek, ever the master of contradiction, has said of his own life; 'everything is the opposite of what it seems'. In truth Zizek is less 'new Europe' than you might think. An avid disciple of modern French and German thought, Zizek's thinking owes far more to the French structuralists than to the likes of Georg Lukács and other such darlings of orthodox marxism. Having lived through Tito's own-brand of socialism in the former Yugoslavia, Zizek belongs to a particular breed of people who have lived through two systems which have sought to shape world politics. Politically and philosophy speaking it therefore comes as no surprise that he embraces a kind of 'Third Way' between French postmodern scepticism of the enlightenment ideals of 'truth', 'reason', 'universality' and 'progress' (embodied by Foucault and Derrida) and Habermas's more positive reworking of those same ideals. Likewise he is at once critical of consumer capitalism propogated by the United States, whilst feeling uncomfortable with what he calls 'vulgar anti-americanism'. On the other hand, he has also criticised globalisation and the mantra of free trade as part of capitalism's 'systemic, anonymous violence', mischievously using the 150th anniversary of the communist manfiesto to argue (against the prevailing postmodern view) for that text's relevance to today's global economic and cultural system.

A left-wing thinker, he is equally cutting about socialism and consumer capitalism. His target is ideology - which he sees just as much in the unquestioning, passive simpleton 'Forrest Gump' rewarded for his obedience in the film of the same name with riches and fame, as with socio-psychology of the victim cited by juvenile delinquants from those in the film West Side Story (to Officer Krupke) to those young neo-nazis in eastern Germany as an excuse for their crimes. Zizek is also deeply distrustful of the ideological concept of the nation (so beloved of the Bush administration) and its deceitful rallying cry 'let's leave aside our petty political and ideological struggles, it's the fate of our nation which is at stake now'.

For Zizek, much of what is wrong with the world is due to the depoliticisation of the people. Both socialism and capitalism are guilty of this in the sense that the two systems encourage a cynical and therefore apolitical citizen: one who is deeply distrustful of the system, but unable or unwilling to believe he can do anything to change it. Likewise it his view that in today's cynical age ideology can afford to reveal itself without losing its efficiency. As has been noted elsewhere, it is rather like the willing customers who, by wearing the logos of their favourite brand, are knowingly walking advertisements of the clothes on their backs.

Zizek's political project is therefore the exposure of the all-pervasiveness of ideology (ie. even when we think we are not being ideological, we are) and a quest for what he calls 'politics proper' - a moment of politicisation which is fleeting, like the turning point of a revolution, before everything once again becomes inscribed into an ideological order. An admirer of the third estate, he is a Danton, rather than a Robespierre whilst he sees politicisation in the civic committees, such as the Czech civic forum and the Slovenian committee for the protection of human rights, which sprung up in eastern-bloc countries as de facto opposition to the party nomenklatura prior to the fall of the Berlin wall.

Anti-intellectualism philosophy

In the context of 'politics proper' you could begin to see Zizek as a political organiser of civil society opposition, a latterday soixante-huitard in the Roland Barthes mould issuing calls to arms to willing student followers and anti-G8 protestors. Yet you could not be more wrong. For a start he attacks the assumption that civil society is a benevolent force, quoting the Oklahoma bombing as a powerful example of how the US discovered 'hundreds of thousands of jerks'. He also states controversially that what we liked about east European dissidents was only possible within a socialist system.

For a thinker of his magnitude and complexity Zizek is also profoundly anti-intellectual. He is disdainful of the left-wing intellectual elite in his own country and one would imagine that, despite his faithful adherence to 'sexy' thinkers, he is somewhat suspicious of the tendency we Europeans have to elevate our intellectuals to the status of would-be cultural ambassadors (think Goethe Institute, Sartre's meeting with Castro in Cuba, and so on). He has made it clear that this tradition is not something that should be repeated in the former eastern bloc, stating in relation to Slovenia that a 'messianic complex with intellectuals in eastern Europe when it gets combined with vulgar anti-Americanism can become extremely dangerous'. For Zizek, this attitude is 'right-wing'. It fundamentally leads to another of his pet-hates: the intellectualised nationalism which was the cause and consequence of the conflict in the Balkans.

In many respects, he is comfortable with the idea of intellectuals being close to institutional politics, believing in overt compromise, the nitty-gritty of meetings, intrigue and engagement. In other words he will get his hands dirty and does so. He supports the ruling party in Slovenia and is scathing of powerful intellectuals who reminisce about left-wing dissidence and make an ideology out of a perceived 'marginality'. His view is that the intellectual faces a professional choice which often may mean accepting the rules of the political game.

Pop-psychology for an enlarged Europe?

Zizek is characteristically difficult to pin-down when it comes to the European Union. For someone who has written a book (ironically?) entitled A Leftist Plea for 'Eurocentrism' he has been critical of Brussels as a dream of a 'neutral, purely technocratic bureaucracy' (particularly in relation to the Balkan conflict). It is difficult to fathom what Zizek would make of the enlarged European union, although it is unlikely to match his image of 'politics proper'. One of his now famous examples cites the banners used in demonstrations by east Germans in the heady final weeks and days of the socialist state. 'Wir sind das Volk' ('we are the people') they proclaimed, the definite article exercising the right of east Germans to be heard as the subject of history. But the fleeting moment was soon over. The banners changed to 'Wir sind ein Volk' ('we are a/ one people') signifying for Zizek the subsumption of east Germans into the western liberal capitalist system.

Clearly, Zizek is no friend of standardisation, of suits and civil servants giving speeches proclaiming harmony, nor of scrambled together constitutions and platitudes patching over old weaknesses and wounds. He will most likely have been delighted by Silvio's 'gaffe' and may be planning his own 'hoax' version with which to impress student followers. As Europeans we should be proud of this export - a rebellious child of disillusioned communists, who is at home amid western European theory and US pop culture and who will not be silenced. Right wing eurocentrics beware!

Notes: Poland, Hungary and Czech Republic signed the letter, whilst at least three other accession countries registered their support, including Slovenia. Naomi Klein; No Logo. Zizek: Japan through a Slovenian Looking Glass. Reflections of Media and Politic and Cinema. InterCommunication no. 14. 1995. Zizek: From Joyce-the-Symptom to the Symptom of Power