Sherlock in Strasbourg: dial G for green crime

Published on

Translation by:

Cafebabel ENG (NS)If ever there were to be the perfect ecological crime, it would be in Strasbourg. The city appears to be a little eco-paradise, and were I Sherlock Holmes himself I’d have to retrace my footsteps and leave…or so I think

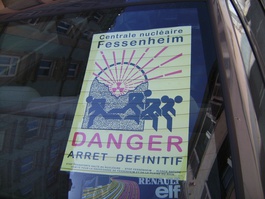

A tramway glides silently across an uninterrupted row of grass. Ordered gardens sit in dark wooden houses from another era, as if they were old paintings from an attic. A strange cristal ball houses a station which has trains running in and out from inside of it. You can hear the sound of an intricate labyrinth of streets in the heart of the historical centre. It sounds like a metal concert comprised of creaking chains and loud bells. I pass an old black Renault negro with a huge yellow sign plastered over its back: ‘Danger. Stop the nuclear station at Fessenheim’. The oldest and potentially most dangerous nuclear plant in France sits on the border with Germany, one hundred kilometres from Strasbourg and far less from the local natural park, Ballons des Vosges. Add the myth of the ‘grand hamster of Alsace’ – the rare hamsters are endangered thanks to ‘urban sprawl’ - and I wonder what other eco-crime this perfect city could have to offer.

A tramway glides silently across an uninterrupted row of grass. Ordered gardens sit in dark wooden houses from another era, as if they were old paintings from an attic. A strange cristal ball houses a station which has trains running in and out from inside of it. You can hear the sound of an intricate labyrinth of streets in the heart of the historical centre. It sounds like a metal concert comprised of creaking chains and loud bells. I pass an old black Renault negro with a huge yellow sign plastered over its back: ‘Danger. Stop the nuclear station at Fessenheim’. The oldest and potentially most dangerous nuclear plant in France sits on the border with Germany, one hundred kilometres from Strasbourg and far less from the local natural park, Ballons des Vosges. Add the myth of the ‘grand hamster of Alsace’ – the rare hamsters are endangered thanks to ‘urban sprawl’ - and I wonder what other eco-crime this perfect city could have to offer.

Eco-chic Strasbourg

‘Strasbourg is an eco-chic city,’ says Manuel Santiago, environmentalist at the La carotte sociale et solidaire (‘social and solidarity carrot’) association. We meet at a small bar in a popular and most recently ‘bourgeois’ neighbourhood. ‘It’s ecology for rich people – those who can afford to use an electric car or the local city bikes do so. But there’s a grey zone beneath this shiny green layer. The bike tariffs are too expensive for students with little resources and those who live in more modest areas, though it’s perfect for tourists.’

See images of 'Strasbourg is bikes' on cafebabel.com

Bikes which are rented for prices that not everyone can afford is perhaps reductionist as a hypothesis of whether it can be valued as an eco-crime in Strasbourg. But food, however, is a potential crime. Glancing at a map, I see that we are close to the Black Forest in Strasbourg – and no, it’s not a sub-Saharan-sized issue. ‘The region of Alsace is quite densely populated,’ continues my green whisperer Manuel Santiago. ‘There’s little space to cultivate here. It creates a problema of alimentary self-sufficiency. We need to develop local agriculture; we’re full of natural resources here. We could create a clean energy network with solar, wind and hydroelectric energy. And of course, we have Fessenheim.’ The yellow pages are chock-a-block with the numbers of environmental lawyers. My finger randomly stops under the name of Julien Schaeffer, of ASA Lawyers, who explains what the most frequent infractions are: industrial constructions built illegally, the contamination of running water and hunting-related crimes, since Alsace is a region full of forest zones.

Green crime centre

As I walk aimlessly through the streets and bridges of this city, I see a series of blue posters about the environment. Starting at ‘The o-zone, Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde’, I move on to ‘A climate which changes!’ and end up at ‘Global warming affects Strasbourg’. The last poster takes me straight to the door of Strasbourg’s environmental law centre, an investigation hub which is part of the university of Strasbourg, opened in 1975.

As I walk aimlessly through the streets and bridges of this city, I see a series of blue posters about the environment. Starting at ‘The o-zone, Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde’, I move on to ‘A climate which changes!’ and end up at ‘Global warming affects Strasbourg’. The last poster takes me straight to the door of Strasbourg’s environmental law centre, an investigation hub which is part of the university of Strasbourg, opened in 1975.

Students and professors here have been studying green crimes here for over thirty-five years. Marthe Lucas is a specialist in ecologic compensation. She disagrees with lawyer Julien Schaeffer’s judgement. ‘You need to add the fact that Strasbourg has a problema with the great ring to the west of it, which will have a strong impact on agricultural land. Then there’s the issue of air quality. There are still too many cars and the atmosphere doesn’t help. Environmentalists believe that the construction of newer traffic zones could aggravate the situation.’

So what are the penalties for such a long list of local crimes? ‘They’re quite soft,’ admits Marie Pierre Camproux, director of the centre. ‘It’s not dissuasive enough to have to pay a fine for an eco-crime. It would be better to have those who committed the crime have to save the contaminated zone.’ Elisabeth Terzic, a young PhD student who focuses on requalifying contaminated zones, adds: ‘The real problem is that a green delinquent wouldn’t even make it to the tribunals.’There are too many crimes, too many victims, too many eco-crimes for an apparently eco-sustainable city. Out from under the magnifying glass as a budding eco-detective such as myself, Strasbourg changes again to become a little eco-paradise which smiles for the camera of a tourist. Strasbourg is the capital of Alsacen, but ir is also a little coastal town in Portugal, a medieval Italian villa or a German metropolis. Strasbourg is Naples, Madrid and Athens. Strasbourg is a city – maybe it’s more perfect than some, maybe it is less virtuous still than others. Strasbourg is Europe. Green crimes surround everyone, be they in Lisbon or Sofia. Maybe your garden is one of the next victims of eco-crime. Finding it out is easy, but we should go deeper under the telescope.

So what are the penalties for such a long list of local crimes? ‘They’re quite soft,’ admits Marie Pierre Camproux, director of the centre. ‘It’s not dissuasive enough to have to pay a fine for an eco-crime. It would be better to have those who committed the crime have to save the contaminated zone.’ Elisabeth Terzic, a young PhD student who focuses on requalifying contaminated zones, adds: ‘The real problem is that a green delinquent wouldn’t even make it to the tribunals.’There are too many crimes, too many victims, too many eco-crimes for an apparently eco-sustainable city. Out from under the magnifying glass as a budding eco-detective such as myself, Strasbourg changes again to become a little eco-paradise which smiles for the camera of a tourist. Strasbourg is the capital of Alsacen, but ir is also a little coastal town in Portugal, a medieval Italian villa or a German metropolis. Strasbourg is Naples, Madrid and Athens. Strasbourg is a city – maybe it’s more perfect than some, maybe it is less virtuous still than others. Strasbourg is Europe. Green crimes surround everyone, be they in Lisbon or Sofia. Maybe your garden is one of the next victims of eco-crime. Finding it out is easy, but we should go deeper under the telescope.

Thanks to Birke Gerold, Cristina Cartes, Tania Gisselbrecht and Jean-Baptiste and Yulia of the cafebabel.com oficial team in Strasbourg

This article is part of cafebabel.com’s 2010-2011 feature focus on Green Europe; read the full set of city special editions

Images: main (cc) Sherlock Holmes/ BBC; main © Gianluca Martelliano

Translated from Strasburgo, l'eco-paradiso perduto: cronaca di un delitto quasi perfetto