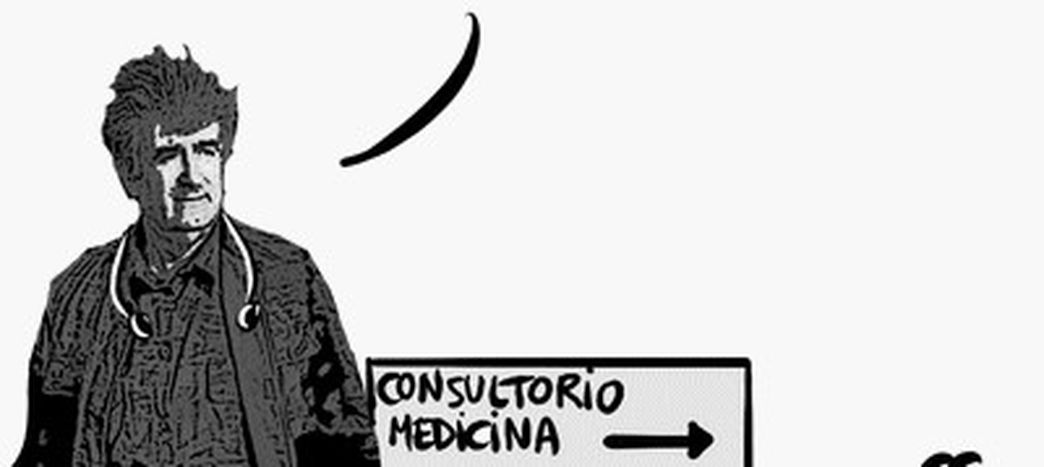

Serbia’s Radovan Karadzic, prisoner bus line number 73

Published on

Translation by:

Nabeelah ShabbirHow the war criminal was arrested in Belgrade on 21 July, and happens in Serbia now

Up until now, the heavily-bearded and bespectacled Dr. Dragan Dabic lived a modest secret life practising alternative medicine in New Belgrade. He wandered around his district like your average next-door neighbour, went shopping and used public transport. His world crashed around him when Serb secret police stopped and arrested him on 21 July. Fingerprints and DNA don’t lie. Dragan Dabic is the most-wanted war criminal from the former Yugoslavia – but the world knows the fugitive better as Radovan Karadzic.

In the Bosnian-Herzegovinian parliament at the beginning of the nineties, the former Bosnian Serb nationalist politician often threatened to wipe out the Bosnian Muslims. At the time Karadzic was head of the Serb democratic party (SDS) and president of the Srpska Republic, which he proclaimed as a Serb autonomous province. With former military commander Ratko Mladic, he attempted to ‘cleanse’ the Serb population through merciless bombings of cities and finally through genocide between 1992 and 1995. The independent Bosnia-Herzegovina was designated, in his view, to become ethnically Serb.

Thirteen years later

Karadzic’s capture wasn’t a dig-him-out-of-a-hole aka Saddam Hussein mediatic affair. Nor did any dramatic night-time negotiations take place during the arrest of former Yugoslav president Slobodan Milosevic. The 63-year-old was observed, identified despite giving a false name and eventually arrested as he took bus number 73, in a bloodless and smooth operation.

Karadzic’s capture wasn’t a dig-him-out-of-a-hole aka Saddam Hussein mediatic affair. Nor did any dramatic night-time negotiations take place during the arrest of former Yugoslav president Slobodan Milosevic. The 63-year-old was observed, identified despite giving a false name and eventually arrested as he took bus number 73, in a bloodless and smooth operation.

After so many years, that became a possible capture very suddenly. In May, pro-European president Boris Tadic won the parliamentary majority, with his government gaining control over the secret services. Until then they had been under the aegis of former nationalist coalition partner and prime minister Vojislav Kostunica, who had been against the handing over of Milosevic.

President Tadic’s political will to co-operate with the Hague was certainly strengthened through an election gift from Brussels. In the midst of the snap elections held in Serbia after the then-province of Kosovo declared independence in February, the EU and Serbia signed a stability and association agreement (SAA) on 29 April.

The juiciest part of the affair came from the behaviour of Milosevic’s socialists (SPS). Their boss was hardly in his grave two years when the coalition was back in arms with the former archenemy; they have been ruling with the democratic party (DS), who Milosevic once had sent to the Hague. New interior minister Ivica Dacic, former acid-tongued speaker for Milosevic and his successor as SPS party leader, hurryied to announce that the Serbian national police under Tadic’s command did not play a role in Karadzic’s arrest.

A grouping of right-wing extremists from the ‘Obraz’ organisation, who gathered in Belgrade on the night of Karadzic’s arrest, was too small to be able to cause real unrest in the Serb capital. The only political force who can do this is Tomislav Nikolic’s Serbian radical party.

The ruling party in Belgrade know that. But eventually getting General Mladic arrested is still a big challenge. Mladic is well-hidden in a tight net of former military and secret service comrades. Just because the defence minister is a Tadic stalwart doesn’t mean that he also actually controls this network. For example, there are ten times more retired generals than active ones in Serbia.

Over in Bosnia-Herzegovina where the bloody traces of Karadzic and Mladic are the clearest, thousands of Bosniaks celebrated the arrest out on the streets. Bosniak politicians seemed satisfied, whilst in Banja Luka, capital of the Srpska Republic and Bosnia’s second largest city, reactions were mixed. Whilst Karadic’s SDS party members complained of an ‘anti-Serb justice’ in the Hague, Milorad Dodik, president of the Sprska Republic, looked content. The political tension on the Sprska Republic will ease since although it was thought Karadzic was hiding in this part of Bosnia-Herzegovina or Montengero, eventually he was caught in the capital.

Dragoslav Dedovic, the author of this article, is a member of the German writer’s network n-ost

Translated from Radovan Karadzic: Verhaftet in der Buslinie Nummer 73