Seraphim Fyntanidis 'the European elections are a form of anti-government protest'

Published on

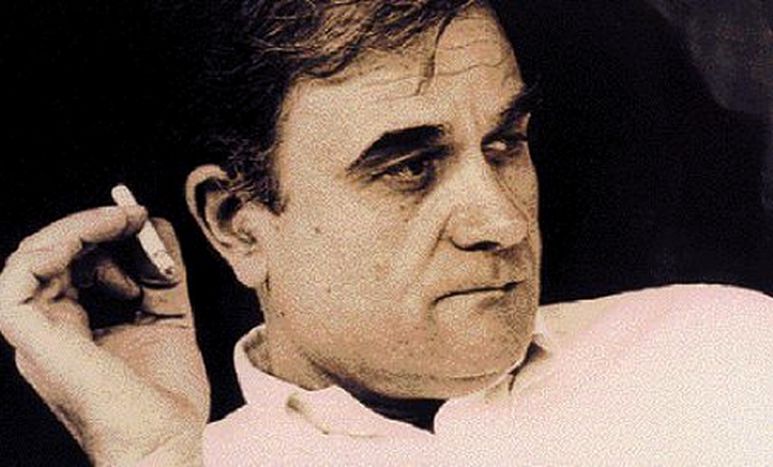

I don't usually watch TV, but when I caught a programme about the modern vision of the Greeks one Sunday, I found myself chatting with its presenter a few days later in the Chalandri district of Athens

There's an expression that says the Greeks always have their hearts in the east but their minds in the west. 'I like the European west,' begins Seraphim Fyntanidi. We meet at the glass television building he works in, with the infamous wooden Trojan horse parked outside it in a calm, residential suburb of the Greek capital. He’s just come out of a meeting, but there are no superficial formalities and the atmosphere is warm and chatty. He is smart, cynical, and when he looks at you, it’s straight in the eyes.'I want to take things from the east, but not to be eastern (as in the Asian culture). We Greeks have a huge advantage - we are surrealistic people and are just not classifiable. We have completely degraded capitalism, socialism and communism. That is why foreigners that come here; they do not want to leave Greece.'

Blood, crown, sperm and Turkey

Fyntanidis was born in Athens on 1937 and has always been a journalist, having working for newspapers such as Ethnos and Apogevmatini. He has been editor of one of the most well-known dailies, Eleftherotypia for three decades. He is currently presenting a Sunday programme on national television NET (Nea Elliniki Tileorasi, 'New Greek Television'), called Chthes, simera, avrio (‘Yesterday, Today, Tomorrow’). He immediately confirms my aversion for TV by making a clearly journalistic statement: ‘Blood, crown, sperm; the three things that sell. This is a two-way relationship. The same thing in Norway would not be very popular, but it's in demand in the Mediterranean. We like gossiping and being outdoors, we do not read a lot, we love conspiracy theories. It's a matter of culture and historical tradition. Greece has a big disadvantage; we haven't lived the three centuries of Renaissance and the one of the enlightenment, because we were under Turkish occupation.’

having working for newspapers such as Ethnos and Apogevmatini. He has been editor of one of the most well-known dailies, Eleftherotypia for three decades. He is currently presenting a Sunday programme on national television NET (Nea Elliniki Tileorasi, 'New Greek Television'), called Chthes, simera, avrio (‘Yesterday, Today, Tomorrow’). He immediately confirms my aversion for TV by making a clearly journalistic statement: ‘Blood, crown, sperm; the three things that sell. This is a two-way relationship. The same thing in Norway would not be very popular, but it's in demand in the Mediterranean. We like gossiping and being outdoors, we do not read a lot, we love conspiracy theories. It's a matter of culture and historical tradition. Greece has a big disadvantage; we haven't lived the three centuries of Renaissance and the one of the enlightenment, because we were under Turkish occupation.’

Fyntanidis originates from Constantinople (today's Istanbul) so it's interesting to know what he thinks of Turkey joining the EU. 'No!' he says. 'It's gentle islamism, but is still islamism. In Turkey, the defence minister comes before the general, and it's the opposite in Europe. In Turkey the army owns banks, insurance companies, industry and coems above politicians. Now (Turkish prime minister Recepp) Erdogan is trying to do a crazy thing. Turkey is a cosmic state that is much further from Europe than the islamism of Erdogan that Europe wants. In order to join the EU, they have to change a lot of things.'

Being Greek in the EU

As for the EU itself, Fyntanidis 'was a great concept that should have been done.’ But now, he argues, there is a difference: the EU is constantly alienating from the initial vision of Jean Monnet and  Robert Schuman because the decisions are taken by the ‘clergy of Brussels’ without asking anyone, he goes on. ‘The bureaucracy in Brussels operates in absentia of the people. There is no parliament that decides; in Strasbourg they only make wishes. There is a deficit of democracy in the EU right now! It is a closed circuit that decides without asking you, it tells you what to do. At least in my country there is parliamentarianism, the government is being controlled. That is the major weakness of the EU, that we do not participate in the decisions and that is what makes the farmer or the fisherman say, ok then, let's grab whatever we can!'

Robert Schuman because the decisions are taken by the ‘clergy of Brussels’ without asking anyone, he goes on. ‘The bureaucracy in Brussels operates in absentia of the people. There is no parliament that decides; in Strasbourg they only make wishes. There is a deficit of democracy in the EU right now! It is a closed circuit that decides without asking you, it tells you what to do. At least in my country there is parliamentarianism, the government is being controlled. That is the major weakness of the EU, that we do not participate in the decisions and that is what makes the farmer or the fisherman say, ok then, let's grab whatever we can!'

But Fyntanidis immediately points out how difficult it is to merge 27 countries in one position. The economic and monetary union was a great step for Greece. ‘We gained economic stability. We always hear about the Franco-German axis, or that Great Britain is constantly against EU policies. When the UK joined the EU in 1973, their newspapers were writing that Europe had yoked to our island. But what about us? What do we do, wait for their decisions?’

Question him about people's concern over the EU, and his answer is one word: 'Subsidy!’ That is not that bad’ 'Yet it's not the only thing!’ he exclaims. ‘But that is how Greeks are, when we have a big difference we go to the European court of justice to find reason because that is in our interest.' Bearing in mind the recent opposition of university professors to the recognition of professional rights to the graduate annexes of European and American universities in Greece, I ask Fyntanidis about the different social groups - labourers, professors, professional unionists often do not even try to approach the EU. Can the EU break these blocks? 'But this is how the system works! The history of humankind is a history of interests. The professors right now are defending their interests. They do not care if something is for the general good, they believe that certain measures will undermine their work. Greeks are introvert. We didn't experience Europe's history, we became an independent state in 1830, we didn't have a clue what was going on in the rest of Europe.' As for ask the European elections and the participation rate, he exclaims: 'So what? Here? The European elections are a form of protest against the government, they blow them and afterwards they go and vote for a party already in power.' As I head out, he remarks: ‘Whatever I told you came straight from my heart!'