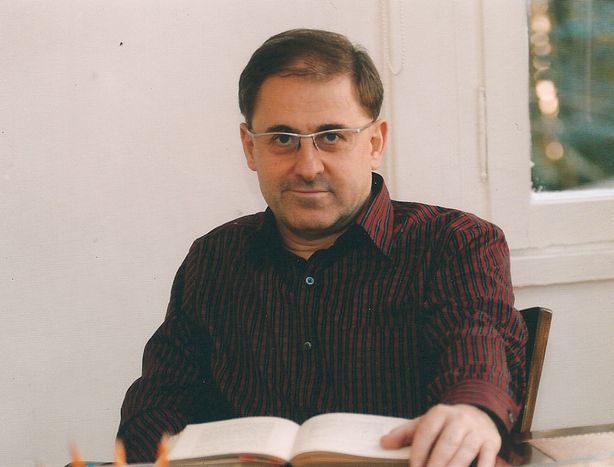

Selçuk Altun: 'Being in a crisis or recovering from one is part of normal life in Turkey'

Published on

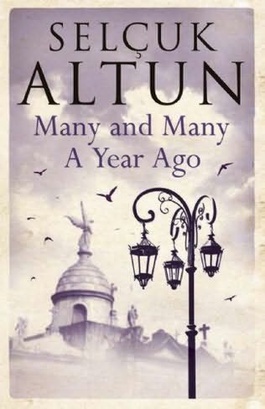

Planning to visit Istanbul when the city will be Europe’s Capital of Culture in 2010? The Turkish writer, columnist and Chelsea supporter’s latest book ‘Many and Many a Year Ago’ is published in English this month, and is an enjoyable way to prepare for a visit

It’s a hot summer’s day when I meet noted Turkish fiction writer Selçuk Altun at London’s popular club for journalists, the Frontline Club. Selçuk is in London to promote his second book to be translated into English, Many and Many a Year Ago (Telegram Books, August 2009), an exciting mystery adventure novel that takes the reader on a trail through Istanbul’s proud Ottoman and Byzantine cultural heritage. Like his previously translated crime novel Songs My Mother Never Taught Me (Telegram Books, July 2008), it explores such underlying themes as the conflict between secularism and religion in contemporary Turkish society.

On his regular trips to London, Selçuk also attends football matches whenever possible. ‘I have been an ardent supporter of Chelsea football club since 1974,’ he proudly exclaims. But like many other successful writers I have interviewed, Selçuk is a quiet man, modest about all his achievements in both the business and literary world. He is a retired vice-chairman of one of Turkey’s largest banks, Yapi Kredi. He did not start writing seriously until towards the end of his banking career in 2004, when he was also made CEO of Yapi Kredi publications, one of Turkey’s largest publishing companies. He is a contributing cultural and media columnist in such Turkish newpapers as the centre-left daily Cumhuriyet.

On his regular trips to London, Selçuk also attends football matches whenever possible. ‘I have been an ardent supporter of Chelsea football club since 1974,’ he proudly exclaims. But like many other successful writers I have interviewed, Selçuk is a quiet man, modest about all his achievements in both the business and literary world. He is a retired vice-chairman of one of Turkey’s largest banks, Yapi Kredi. He did not start writing seriously until towards the end of his banking career in 2004, when he was also made CEO of Yapi Kredi publications, one of Turkey’s largest publishing companies. He is a contributing cultural and media columnist in such Turkish newpapers as the centre-left daily Cumhuriyet.

Turkish writing: three stumbling blocks

‘It was my mother’s love of books that inspired me to write,’ says the graduate of Bosphorus University in Istanbul. Amongst his favourite authors he lists two late writers, the Austrian Thomas Bernhard and Turkish modernist poet Oktay Rifat. Selçuk has another three books under his belt, which have been published in Turkish. ‘But the lot of being a successful author in Turkey is not always a happy one,’ warns the married father-of-one, whose daughter is called Elvin. Writers face various challenges, including being threatened by both secular and religious political forces. ‘My third novel Taste of the Bullet (2003) was blacklisted in Turkey by a major media conglomerate, because it criticised the purchase of state media companies by the private sector,’ he remarks.

'Turkey is experiencing a clash of cultures between the secular and religious'

Nor does it help that Turkey lacks the well developed literate culture that exists in the rest of Europe. Both at home and abroad, people tend not to have as well developed an enthusiasm for reading, whether the format is the internet, books, magazines or newspapers. This, Selçuk says, is in part due to a ‘lack of a sufficiently developed reading culture thanks to historic poor literacy levels, living standards, religious attitudes and the fact that nearly half the population is under twenty five. My first novel’s premier edition sold 15, 000 copies and met subsequent critical acclaim,’ Selçuk explains. But official figures for his subsequent books and editions have done less well. ‘That’s due in part to my work being extensively pirated.’ Recently Ankara introduced a new system of copyright protection, so now every officially published book must carry a government security tag.

Europe and Turkey

EU writers do not have to face the prospect of being blacklisted or their work extensively pirated. Which brings us to the broader subject of Turkey’s EU membership bid. ‘I doubt that Turkey will join the EU in his lifetime,’ he comments. ‘The current climate does not help; Turkey is a bit puzzled at Europe’s reaction to the economic downturn. In Turkey either being in a crisis or recovering from one is part of normal life. Not that long ago it had an inflation rate in three figures. In Europe, political leaders like French president Nicolas Sarkozy are not happy with such a prospect of Turkey becoming an EU state. To many EU politicians Turkey is not a European country, nor does it help that it is predominately muslim and has a muslim government in control in Ankara. Turkey is experiencing a clash of cultures between the secular and religious. There are those who complain that modern Turkey is not eastern enough while other complains the reverse,’ he says.

EU writers do not have to face the prospect of being blacklisted or their work extensively pirated. Which brings us to the broader subject of Turkey’s EU membership bid. ‘I doubt that Turkey will join the EU in his lifetime,’ he comments. ‘The current climate does not help; Turkey is a bit puzzled at Europe’s reaction to the economic downturn. In Turkey either being in a crisis or recovering from one is part of normal life. Not that long ago it had an inflation rate in three figures. In Europe, political leaders like French president Nicolas Sarkozy are not happy with such a prospect of Turkey becoming an EU state. To many EU politicians Turkey is not a European country, nor does it help that it is predominately muslim and has a muslim government in control in Ankara. Turkey is experiencing a clash of cultures between the secular and religious. There are those who complain that modern Turkey is not eastern enough while other complains the reverse,’ he says.

'Byzantine heritage has contributed so much, from the introduction of forks to the very knowledge that sparked Europe’s renaissance'

This battle between the various interests is being played both at home and abroad. Take for example the failure of Ankara to send Byzantine antiquities to the recent Byzantine exhibition at London’s Royal Academy. It also failed to send popular secular writers to the 2008 Frankfurt Book Fair that was celebrating Turkish literature. ‘The current government in Ankara appears to have little real interest in Turkey’s contemporary or Byzantine heritage that has contributed so much to the development of the modern world,' Selçuk says, 'from the introduction of forks for eating to the very knowledge that sparked Europe’s renaissance.’

Altun’s next book, Sultan of Byzantium, will provide a historical-fictional account of the emperor and his descendents. It will be available in English and go on sale throughout Europe