Seeking asylum in Athens: the pitfalls of Piraeus

Published on

Translation by:

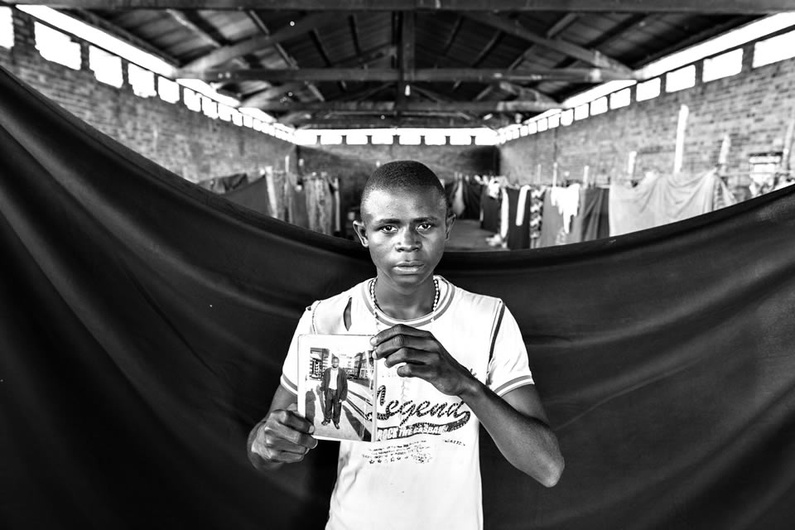

Nicola PotterVenturing from sub-Saharan Africa and the Middle-East, migrants risk their lives crossing the Mediterranean to flee the wars ravaging their countries. Arriving on Greek soil, however, they are very quickly confronted with a whole other set of problems.

Chouan, a 27 year-old Syrian who has lived in Athens for 8 years is one of a lucky few. In his apartment in a popular area of Athens, he’s been lodging some of his family for 3 months: his mother, Bakira; his father, Amin; his sister, Susu, and his friend, Shehmoos, who has just arrived from Aleppo. Like a lot of Syrian refugees, they braved great danger to escape the chaos that has reigned in the Middle-East since 2011, between civil war and the rise of the Islamic State.

ISIS, Bachar and the family jewels

Not everyone, however, has experienced the joy of reunion. Sitting alone on a Persian rug next to the window, 24 year-old Youssef stares into space, transfixed. He left for Greece on 14th April last year, joining one of the recent waves of migration. But before arriving safe and sound in the port of Piraeus and being taken in by his neighbour, Chouhan, the young Syrian experienced a living nightmare.

“I’m going to tell you my story from the beginning”, he murmurs in English, a hint of a tear in his eye. Two months earlier when Youssef learned that his father had been taken, then killed, by ISIS, he didn’t hesitate for a second. He had to flee Syria and come to Europe. His mother, who is still in Syria, also encouraged him to leave. She couldn’t bear the thought of her son being forced to leave for national service. Deserting Bachar Al Assad’s army, it was on foot that Youssef left Arfin - his small Kurdish town not far from Aleppo - for the Turkish border. It took a week by coach with a group of Pakistanis to reach Izmir, Turkey. “The conditions were atrocious, we were all piled on top of each other” he recounts.

By selling the gold family jewels, Youssef managed to raise 1,000 dollars – the exact amount needed for the fare from the port of Izmir to Piraeus. “The dinghy was about to burst, there were 32 of us onboard, including 3 woman and 6 children. The water even came in. We almost sank”, recalls Youssef, still overwhelmed. Forty-five minutes into the journey, after arriving on the island of Lesbos, the young immigrant was held in a centre for 3 days. After hours of interrogation at the police station, the Greek police gave him 6 months to leave Greece.

No home from home

Millions of others have crossed the sea just like Youssef. According to the UNHCR, since 1st January 2015, 36,390 migrants have arrived at Europe’s coastline. The year 2014 represented a record high compared with 2013, when 219,000 people made the journey. In Greece, due to a fault in the arrival system, migrants are left empty handed, to their own devices as soon as they arrive. Those who still have some money can find a hotel room, those who have nothing wander the streets and squares. They sleep in groups - including women and children - in the city’s underground.

For most migrants Greece is a transitory country. The ultimate aim is to reach Germany or Sweden. Youssef is keen to get a boat to Italy to eventually reach Switzerland. A vain wish given the risks and legal constraints such a journey poses. From the moment migrants apply for asylum, the Dublin II regulation dictates that they are systematically sent back to the Schengen country to which they initially immigrated. For Youssef and others like him, this means they are ‘trapped’ in Greece.

For most migrants Greece is a transitory country. The ultimate aim is to reach Germany or Sweden. Youssef is keen to get a boat to Italy to eventually reach Switzerland. A vain wish given the risks and legal constraints such a journey poses. From the moment migrants apply for asylum, the Dublin II regulation dictates that they are systematically sent back to the Schengen country to which they initially immigrated. For Youssef and others like him, this means they are ‘trapped’ in Greece.

As one of the countries on the frontline of this issue, the Greek government plans to apply for European funding to provide welcome centres and close the current detention centres within 100 days. According to the opposition, Syriza’s liberal immigration policies encourage the influx of migrants. With their eye on the tourist season, some of the local mayors on Greece’s islands are scaremongering. “Imagine tourists drinking coffee while a boat of migrants comes ashore”, rumbled the mayor of Kos during a televised debate. Some people, like the mayor of Lesbos, don’t shy away from talking frankly about “invasion”.

These statements echo the failure of the country’s migration policy. The previous, right-wing government, led by Antonis Samaras, intended to make conditions in detention centres unbearable in order to dissuade migrants from making the journey. At the time, the state had launched a large scale search for illegal immigrants ironically named “Xenios Zeus” (the God of hospitality).

At Amygdaleza - a camp built in 2012 near Athens, to detain adult and child refugees and migrants alike - cases of torture have been reported. Notably, Greece has been condemned by the European Court of Human Rights and forced to pay a 1.5 million euro fine relating to the conditions at these detention centres.

"Immigration Mutation"

Ahmed Moavia, president of the Greek forum for migrants, has taken on the role of mediator between the Greek government and other organisations. He believes the situation needs urgent attention. “We need to correct the errors of the past” he affirms. Ahmed believes that the fault lies with the European Union, incapable of finding an adequate solution to the problem. “The EU must take diplomatic initiatives and bring democratic values to Syria, Libya and Iraq. Immigration is mutating. In the aftermath of the wars raging in Africa and the Middle-East, the majority of immigrants today are women and children. Before, it was mostly men who sent money to their families” he stresses.

In another apartment kindly borrowed from a friend, 13 year-old Latchi has lived in Greece with her family for 2 years. Like lots of teenagers, she’s stubborn and fashion conscious, but her adolescence will be forever lost to the war. Latchi has had no news from her Syrian friends, and hasn’t set foot in a school since she arrived in Europe. She learns Greek from watching TV. During this time, her 2 brothers, aged 14 and 16, have worked at the market for a few euros allowing them to bring home some food. To provide for the family, father, Ahmad, has a brother in Denmark who sometimes sends them money. He would like the family to join him there, but for the moment they are stuck in Greece, with their fate postponed indefinitely.

All words recorded by Chloé Emmanouilidis in Athens.

Translated from Réfugiés d'Athènes : le pire du Pirée