Science of the EU: back to the big bang

Published on

As I stood on the plateau of Chajnantor in northern Chile, 5000 meters above sea level, I was not only reporting about the inauguration of the second biggest scientific project of mankind. I could also look back into Europe’s birth and see how powerful its idea has become

Dust swirls over the surface and sunrays hit the ground mercilessly. In the midst of this rough and yet beautiful Chilean no man’s land 66 gigantic antennas are pointing to the sky. This is the atacama large millimeter array (ALMA). Here, in the driest desert on earth, scientists from Europe, the US, East Asia and Chile are looking with an enormous radio telescope for the beginning of the universe, the birth of stars and planets.

EUronomy

When Robert Schuman spoke on 9 May 1950 about his idea of a united Europe, it was not only the beginning of a multi-state economic and political union - a bureaucracy that decides how crooked a cucumber in your local supermarket is allowed to be. It was, as astronomers would phrase it, the ‘big bang’ which created a new mindset. It was a moment in which a minister who had survived two world wars made not only a giant leap for himself, but also for mankind in Europe. The leap was about overcoming past struggles and concepts of the enemy, and creating something greater that the sum of its parts.

At ALMA, I interview a French astronomer, speak with a Dutch engineer, receive explanations about antennas from an Italian constructor and chat with Spaniards, Germans and Brits. Europe is building more than a third of a project that will change how we see the universe. Europe is doing this together. All the scientists that I talk to explain how hard it is to coordinate such an international project. ‘At least 50% of the problems are caused by a lack of communication. We are talking about real bugs that cost money,’ says Denis Barkats, a researcher from France.

The others

However, none of them mention the problems and cultural shocks within the European astronomy organisation, ESO. It is always about how hard it is to work with Chileans, Americans or Japanese. What might have seemed unrealistic decades ago is now something normal for these scientists. They feel European, share the same basis and have something in common. One might argue that the European southern observatory (ESO) is not an organisation that is directly connected to the EU. It also includes EU-outsiders (such as Switzerland); but this is not the point to make. People have said the economic crisis which has been racking Europe since 2008 is also partly an identity crisis. Even worse, it is about the fact that Europe has no identity.

Seeing how European scientists collaborate is an experiment in vivo that proves this theory wrong. Europe definitely has a common identity. It lives, pulsates and enables countries to do things that they could not do on their own. One example is what these scientists do in the Chilean nowhere. To put it in perspective: If we, Europeans, are doing research on galaxies that represent the cradle of our universe, we should also be able to find one common mindset. 63 years on and counting, it only has to connect us across a few thousand kilometers and not across billions of light years.

Follow the author, a science writer, on twitter

This article is part of a special edition marking 'Europe Day', created by winners of the Forum of European Journalist Students (FEJS) 'Imagining Europe' event in Utrecht, April 2013, in collaboration with cafebabel.com

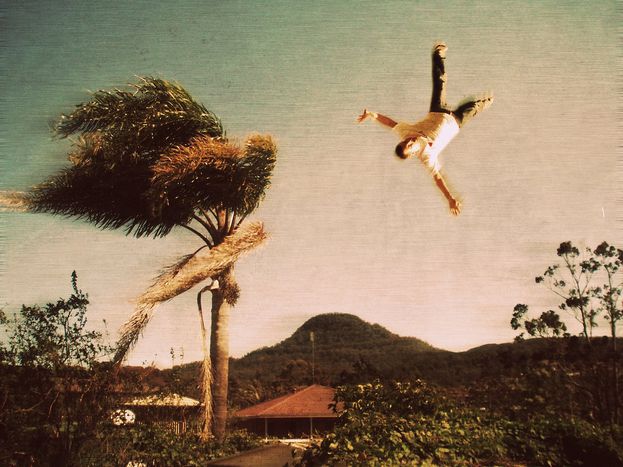

Images: main (cc) Kaptain Kobold/ flickr/ official twitter page; in-text, 5000-metre-high Chajnantor plateau in Chile’s Atacama region shows the Southern Milky Way Above ALMA (cc) European Southern Observatory/ flickr