"Satire is a buffer between the authorities and the society"

Published on

Translation by:

Paweł KasprzykWhen Jacek Woźniak, an artist and journalist, moved to Paris in 1982, the career of Jean Cabut, the French cartoon satire icon, was in full swing.

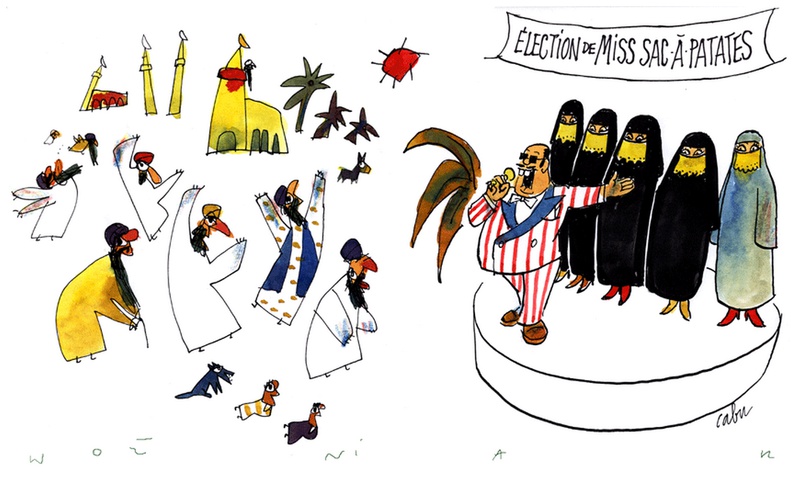

Both artists soon became friends and brought out, among other things, the Les Impubliables [The Unpublished] drawing collection. Little did they know that on 7 January, 2015, Cabut would be murdered in the name of Allah in Charlie Hebdo's office.

I am meeting with Jacek Woźniak in Le Marais, a historic district of Paris, near his studio and the editorial office of Le Canard enchaîné. I am excited to meet this haughty and eccentric artist. After all, his life has been very successful.

He has published in such papers as Le Monde, La Libération and Le Canard enchaîné, not to mention his pictures, posters and CD labels, which are all highly valued around the world. There is also his cooperation with the likes of Manu Chao and Archie Sheep. To my astonishment, Woźniak turns out to be a remarkably modest and approachable man. He greets me with "Call me Jack", although I could well be his daughter. For a moment I wonder whether things would be the same if we were in Poland.

Cabu is gone

The Poland left by Woźniak was a hostile country for independent artists, with censorship and propaganda flourishing all over the place. The artist found his safe haven in France, where the public appreciated his original style, alluding to the works of Joan Miro, Wasilij Kandinski and others. The simplicity and expressiveness of his paintings make up a reverberating medium capable of spreading, for instance satirical, content articulately. Jacek Woźniak's world abounds in energy and colour.

It was this colour that struck up the friendship between him and Jean Cabut, also known as "Cabu". "I was colouring his drawings in as he was not interested in colours", recalls Woźniak. "He used coloured pencils for children - that was Cabu all over. The first drawings I worked on were those for 'Club Dorothée', the broadcast responsible for Cabu's later popularity."

After the Charlie Hebdo shooting, when Cabut was killed, the French felt as if somebody had taken away a part of their childhood: the late comic strip artist played an important role in their growing up. "I did not acknowledge his death until a week after the tragedy", says Woźniak. "What is interesting is that the Kouachi brothers [the shooters, ed.] were born in France and they may have even watched 'Club Dorothée'," he adds after a while. "Something must have happened when they were growing up. People often say that prison experiences change the man."

We are meeting two weeks after the shooting: France is still in deep mourning and the world starts to give in to an Islamophobic mood maintained by the populist discourse of political parties like the National Front or UKIP. Pegida is crawling out of Dresden in Germany, spitting racist slogans. According to Woźniak, however, the politics of terrorism should not be used to excuse or restrain because it is a complicated and confidential sphere. "We have no access to a lot of information, but these are economic games. It is religion that plays the leading role, politics has got nothing to say," he explains.

We are meeting two weeks after the shooting: France is still in deep mourning and the world starts to give in to an Islamophobic mood maintained by the populist discourse of political parties like the National Front or UKIP. Pegida is crawling out of Dresden in Germany, spitting racist slogans. According to Woźniak, however, the politics of terrorism should not be used to excuse or restrain because it is a complicated and confidential sphere. "We have no access to a lot of information, but these are economic games. It is religion that plays the leading role, politics has got nothing to say," he explains.

And since this confidential sphere is to remain confidential for as long as possible, educational systems worldwide are caring less and less for bringing up critically-thinking individuals."Today, children are not taught to oppose: they are taught how to earn money, and nothing more," Woźniak ruthlessly criticises the influence of capitalism on education. "European education is an artificial system and it lost itself many years ago. Nowadays, young people are not taught tolerance but how to pass exams," he comments.

What relationships, then, are there between education, upbringing and freedom in today's democratic society? "At the funeral of Tignous, Taubira [the French Minister of Justice, ed.] said that we have got the impression that we have already achieved everything, including the freedom of speech. But freedom is not something you achieve once and for all: it is a process which has to be maintained," explains the artist.

It is not about religion, it is about money

Even though he has been living in Paris for 33 years, Jacek Woźniak regularly visits Poland, which he thinks took the wrong path feeding bloodthirsty capitalism, which is turning Poles into an army of consumerist conformists. "The changes we wanted to introduce were not about this," he says. At the same time he agrees that Poland is not the only country trapped in the mammon's grip. "Consumption and religion are two forms of manipulation. The religious one is also a form of mind control," explains the artist. "When you control a group of people, when something like the Islamic State – abounding in crude oil – is brought to life, then it is not about religion, it is about money."

How grand a role the money plays could perhaps be told by the politicians w ho were posing for a photo during the Republican march on the Sunday of 11 January. Over one and a half million people took to the streets of Paris in order to pay tribute to the victims of the shooting and to condemn an attempt on the freedom of speech. "The freedom of speech is not a partial freedom," Woźniak still remembers the time he spent in Poland, when he was involved in working for the Solidarity movement and writing in Polytyka and Wryj satirical magazines, the latter found by the artist himself. "When I was working in the Polityka and Życie literackie papers, each and every magazine had its own censor."

ho were posing for a photo during the Republican march on the Sunday of 11 January. Over one and a half million people took to the streets of Paris in order to pay tribute to the victims of the shooting and to condemn an attempt on the freedom of speech. "The freedom of speech is not a partial freedom," Woźniak still remembers the time he spent in Poland, when he was involved in working for the Solidarity movement and writing in Polytyka and Wryj satirical magazines, the latter found by the artist himself. "When I was working in the Polityka and Życie literackie papers, each and every magazine had its own censor."

There were none in France of 1982, when Woźniak got there: they were replaced by a customs-and-capitalism-based self-censorship. "Nobody wanted to publish cartoons with the Pope in a regular newspaper – it would simply be inappropriate," he recalls. "And there were the advertisements – Bouygues [a French giant of communications and real-estate industry, ed.] would not be made fun of by a paper with its ads inside."

Every court has a jester

Can we laugh at everything in Europe, then? How to approach the issue of blasphemy in multicultural and multi-religious societies? "In such a society, if you begin to mind everyone and everything, you will achieve nothing. Or you will be very proper and very artificial. Plastic, just like that," Woźniak states. "Conflicts must occur if we want to move forwards. An exchange of views generates the thinking that maybe not only the one with power and money is in the right."

In a liberal society, negation, mockery, caricature, comedy and the grotesque are key elements in this constructive criticism. "Satire is a buffer between the authorities and the society," explains Woźniak. "It cushions the shock. If Catholic popes and Muslim ulamas had their own jesters, there would be no problems, no tragedies."

Though it is hard not to do justice to the logical conclusions drawn by Woźniak, a question arises whether logic and sober reasoning have ever played any part in the ways of zealots blinded by the holy war. Understanding and solidarity allay our fears of what may yet come, but will they be able to prevent it?

We still recall those Kalashnikovs aiming at the unarmed pencils. This seems like the ultimate symbol of inequality in this schizophrenic fight.

Translated from Jacek Woźniak: „Satyra jest buforem między władzą i społeczeństwem”