Rome: Europe = shops

Published on

Translation by:

neil saddington

neil saddington

We continue our series of articles visiting the streets of Europe which carry the continent’s name. In this episode, shopping and lessons in a non-existent Europeanism at the heart of Eur(ope?)

Europe has most definitely not found a home on viale Europa, a street in Rome. And yet it appears to have been built for that very reason. You can find the street in a district which, even if by name only, honours 'Eur'(ope) – (see box below).

Eurtours without Europe

Romans would never dream of associating viale Europa with anything remotely to do with Europe. Here, viale Europa basically means three things: the Italian Ministry for Communication ('Ministero della Communicazione'), the headquarters of the Italian post office and the only through-road in an area dominated by offices, agencies, public institutions, museums and other government offices, all fashioned in what can only be described as fascist-style architecture.

Yet I find it hard to resign myself to this image of the only Roman street to carry the name Europa, and so I turn to the words of Rossella Favo, a specialist city guide who works for 'Suerte Itinerarte', a Rome-based travel agency. 'Viale Europa? Nothing special. Just shops, shops, and more shops. No mention whatsoever of the literary and historical contributions that this viale could make to Europe.' For the past two years Rossella has organised cultural tours of the area on behalf of Eur Spa, the company managing the area. 'On the other hand, no other street in the cities of Europe fairs much better. Located in the extreme outskirts of Roma, it’s known purely thanks to its proximity to a shopping centre.'

Yet I find it hard to resign myself to this image of the only Roman street to carry the name Europa, and so I turn to the words of Rossella Favo, a specialist city guide who works for 'Suerte Itinerarte', a Rome-based travel agency. 'Viale Europa? Nothing special. Just shops, shops, and more shops. No mention whatsoever of the literary and historical contributions that this viale could make to Europe.' For the past two years Rossella has organised cultural tours of the area on behalf of Eur Spa, the company managing the area. 'On the other hand, no other street in the cities of Europe fairs much better. Located in the extreme outskirts of Roma, it’s known purely thanks to its proximity to a shopping centre.'

Lessons from the newsstand: media and the EU

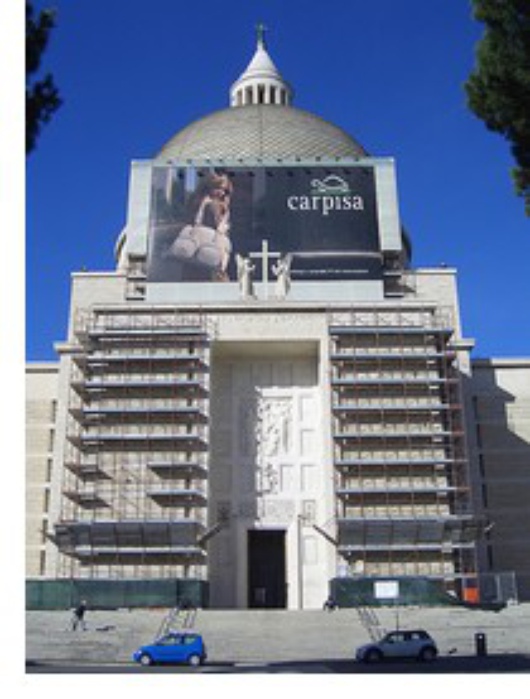

At one end of viale Europa you find the long via Cristoforo Colombi (which joins the city to the sea). At the other, you have the imposing Basilica dei Santi Pietro e Paolo, which dominates the neighbourhood and which ought to have been Mussolini’s mausoleum, if the original plans are to be believed. Mussolini would undoubtedly be turning in his grave, howver, if he saw the famous turtle motif (the logo of a famous Italian brand of handbags and luggage), standing out directly opposite the Basilica’s façade, which is currently undergoing renovation work.

At one end of viale Europa you find the long via Cristoforo Colombi (which joins the city to the sea). At the other, you have the imposing Basilica dei Santi Pietro e Paolo, which dominates the neighbourhood and which ought to have been Mussolini’s mausoleum, if the original plans are to be believed. Mussolini would undoubtedly be turning in his grave, howver, if he saw the famous turtle motif (the logo of a famous Italian brand of handbags and luggage), standing out directly opposite the Basilica’s façade, which is currently undergoing renovation work.

One sunny Saturday morning, I finally venture down viale Europa in the search of the hidden links between logos and topos. But, unfortunately, the words of the city guide prove to be true: just shops. If this weren’t bad enough, the only bookshop on viale Europa doesn’t even have a section on the European Union. 'We don’t sell any of those type of books because the people who come here aren’t interested in them,' bookshop owner Marcello Consentino explains to me. 'They only ask for novels or school books.'

This says a lot about the resources set aside by Italian schools for European Studies. My bookshop owner knows nothing about the community-based projects aimed at increasing cultural understanding, such as Cultura 2000, but rather has his own idea about Europe. 'Europe doesn’t help anyone. They impose things upon us, like speed-limits on the motorway (not true, ndr) but don’t look at balancing out the pay-rates, which are a lot lower in Italy.'

When I get close to the busiest newsstand on the street, the old owner barks at me rudely, 'Journalist? See, it’s full of prostitutes along here.' In reality, at 11am on a Saturday morning, there are no prostitutes. When I try to explain to him that the European commission provides measures for the prevention of human trafficking, he cuts me short and tells me to talk to his son.

When I get close to the busiest newsstand on the street, the old owner barks at me rudely, 'Journalist? See, it’s full of prostitutes along here.' In reality, at 11am on a Saturday morning, there are no prostitutes. When I try to explain to him that the European commission provides measures for the prevention of human trafficking, he cuts me short and tells me to talk to his son.

Luca Palma is extremely busy, but kindly shows me the many foreign language newspaper on offer 'because we have a lot of customers from foreign countries.' Customers, it would appear, who only read trashy English and French magazines.  Those who have regular contact with the world of journalism ought to know exactly how those types of magazine talk about Europe, 'sparingly and badly,' says the newspaper seller. 'Italian journalists only talk about Europe when there is a clear link to national politics.'

Those who have regular contact with the world of journalism ought to know exactly how those types of magazine talk about Europe, 'sparingly and badly,' says the newspaper seller. 'Italian journalists only talk about Europe when there is a clear link to national politics.'

Refined clothes shops, shoe shops, mobile phone shops, jewellery shops all line the two sides of the street. As with every Saturday morning dedicated to shopping, shop owners and shop assistants are busy rushing about serving their customers. The young journalist who wants to talk about Europe is not particularly welcome … business is business! I sadly walk along the street, through the red leaves already fallen from the trees. There is nothing left for me to do but go shopping, the only thing viale Europa has to offer those who venture down her.

EUR - not 'Europe', but 'Esposizione Universale Roma'

Italian director Federico Fellini was fascinated by L’Eur, where he actually filmed his episode of Baccaccio 70 and wrote 'L’Eur is a very good-natured district to those who make a living through images.'

Italian director Federico Fellini was fascinated by L’Eur, where he actually filmed his episode of Baccaccio 70 and wrote 'L’Eur is a very good-natured district to those who make a living through images.'

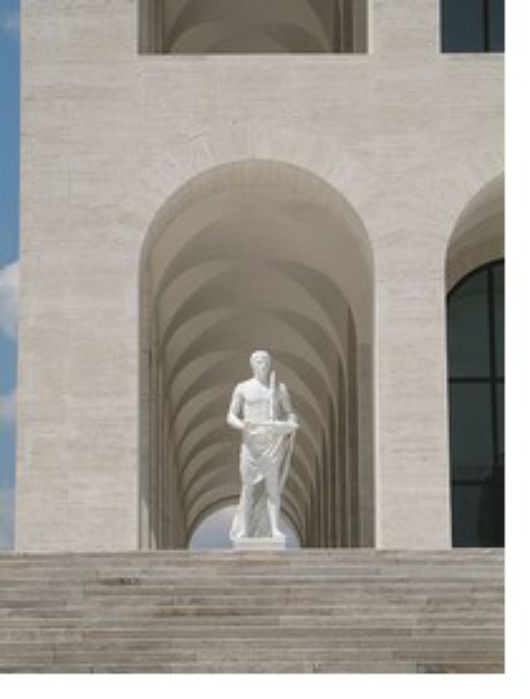

The first few bricks of l’Eur (an abbreviation of L’Esposizione Universale di Roma or Rome World Fair), were laid in 1931. Work was meant to be finished in 1942, ready for a world fair in celebration of the 20th anniversary of the 192 March on Rome. As a result of the Second World War, the World Fair was cancelled and work therefore continued until the end of the seventies, ready for the Rome Olympics. L’Eur represents the only alternative district in the historical 'old town', and is one of the most modern parts of the city. Other streets are also dedicated to continents: viale Europa is joined by viale America and piazzale Asia.

With our series 'The Streets of Europe', discover the squares and streets of Europe’s biggest cities that carry the name 'Europa'. Next stop: Place de l’Europe in Rennes, France on 13 January. Read our last visit: EuropaPlatz, Berlin

In-text photos: View of Viale Europa de Roma, Basilica San Pietro and San Paolo under renovation, news booth, reviews (Tiziana Sforza), EUR building detail in Rome (gengish/ Flickr)

Translated from Qui Roma. Viale Europa, questa sconosciuta