romanian journalism: the new generation

Published on

Translation by:

Hayley WoodIn Bucharest, a group of young journalists disillusioned by mainstream media have opted to live together in a big house which they have converted into a newsroom and social hub. Open to the public, this unusual building is the source of a series of journalistic experiments which are shaking up the landscape of Romanian media.

Spring transforms the Romanian capital. Bikes and roller skates are out on the streets and barbecues fill the air with the smell of grilled meat. In Strada Viitorului, parents sit outside their houses chatting in the sunshine, whilst their children play football. Radu and Stefan are talking and smoking at the back of the yard at number 154. "Vlad's upstairs," they tell me. On the top floor, Vlad, barefoot on the carpeted floor, is working on his computer. A can of beer takes centre stage on the desk amongst various sheets of paper and magazines. Not far off, a dummy's head adorned with a Russian fur hat watches us closely. It is in this room that Vlad, Radu, Stefan and other young editors have brought Casa Jurnalistului, "the journalist house", to life.

swimming against the mainstream

Before he set up Casa Jurnalistului in 2012, Vlad worked in a newsroom for two years. He has created this independent and publicly-open space with a group of other journalists who share his rejection of mass media as being "in the hands of politicians and big business." Here, the public can watch them at work and observe their writing process: "at first, everyone thought this was a crazy idea, but it works better than I'd hoped. It's become completely natural and normal for me to work this way."

In addition to maintaining a website and a team of reporters, the members of Casa Jurnalistului organise events in their basement, where they present their latest creations, beers in hand. Last January, nearly 200 people came to watch the showing of an episode of their documentary series on Romania's unusual religions.

Many people have turned to them to follow current events, whether it's Radu covering events in Ukraine or the demonstrations against plans for a gold mine at Roșia Montană. This was an issue which shook Romania between August and December 2013, and forced the government to reverse their decision. Vlad believes that Casa Jurnalistului had "a positive influence" on the public's awareness of the issue. "People started to ask questions about Roșia Montană that the mainstream media weren't answering. But we were on the ground, and we knew who and how to ask the right questions", he explains.

Many people have turned to them to follow current events, whether it's Radu covering events in Ukraine or the demonstrations against plans for a gold mine at Roșia Montană. This was an issue which shook Romania between August and December 2013, and forced the government to reverse their decision. Vlad believes that Casa Jurnalistului had "a positive influence" on the public's awareness of the issue. "People started to ask questions about Roșia Montană that the mainstream media weren't answering. But we were on the ground, and we knew who and how to ask the right questions", he explains.

Politicians hate them, particularly those accused of corruption, the prime targets of many of their articles. Other journalists vary in their reactions: "some support us, others don't understand the initiative". And some are suspicious: "we have this paranoia in Romania that all journalists are under the thumb of politicans, that they always have a hidden agenda. But we are completely independent."

"diy" journalism

In order to pay their rent and make ends meet, the journalists contribute articles to other magazines and appeal for donations. Vlad doesn't intend Casa Jurnalistului to apply for charity status: "I don't see the point. We don't need much money." When they go away to report, they stay in people's houses, hitch-hike or pick up hitch-hikers, and make do with what they have: "this is an advantage, because we get close to people. It fits better with our writing style, which is a bit gonzo", he adds. Because of this personal angle they sometimes uncover things which other journalists would not find. During the horsemeat scandal, Radu and other reporters investigated the Doly Com abattoir. The man who picked them up hitch-hiking turned out to be a former security guard at that very abattoir. He gave them information about the secret abattoirs and even showed them where to find one.

Vlad can't see himself working in any other way: "unlike in my old job, I can take the time to properly understand what's going on. When I'm done, each article is exactly the way I want it, from the text to the photos."

stylistic experiments

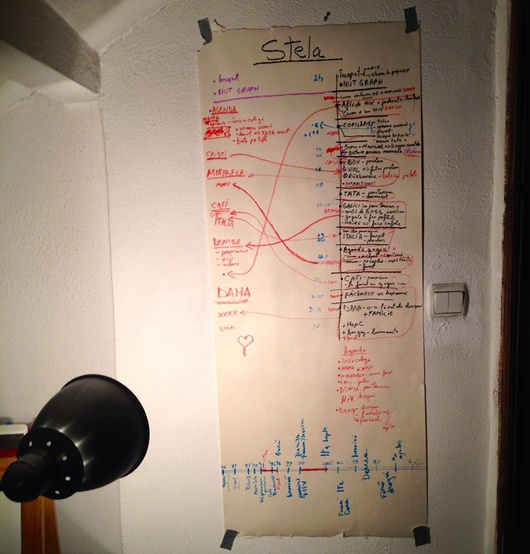

A long sheet of paper pinned to the wall draws my attention. Under the heading "Stela", red arrows crisscross and connect up names with fragments of sentences: "Stefan is experimenting with a new narrative style. He's writing a profile of someone using only the voice of that person, preserving the way they talk. The journalist doesn't figure in the narrative. Stela talks, and the text is constructed by the journalist after an interview of a few hours." In their eyes, journalism is not set in stone. As long as authenticity is respected, a story can be told in various ways.

At the same time, in the yard, Stela's friends are preparing her surprise birthday party. The barbecue sizzles and a few people are blowing up condoms by way of decoration. Stela arrives, "la multi ani!" (happy birthday!) bursts out from all sides and blends with the rhythms of the manele and the football hitting the door outside. The article, "Am fost smardoaică" (I was wild), will be published a few days later. It tells the story of Stela's life, her loves, her setbacks, and her fight against HIV. In a single week, the text is viewed 20,000 times and "liked" 6000 times. Journalism has found its human form.

At the same time, in the yard, Stela's friends are preparing her surprise birthday party. The barbecue sizzles and a few people are blowing up condoms by way of decoration. Stela arrives, "la multi ani!" (happy birthday!) bursts out from all sides and blends with the rhythms of the manele and the football hitting the door outside. The article, "Am fost smardoaică" (I was wild), will be published a few days later. It tells the story of Stela's life, her loves, her setbacks, and her fight against HIV. In a single week, the text is viewed 20,000 times and "liked" 6000 times. Journalism has found its human form.

Translated from Roumanie : journalistes nouvelle génération