Rise of Greenlandic cinema in Denmark

Published on

'You will only find Greenlandic cultural projects in public libraries in Denmark,' prophesises one Dane I meet. However awareness of the minority’s work is on the rise as I find in Copenhagen’s north atlantic centre's biannual film festival - for the first time, it focuses exclusively on Greenlandic film

In early 2012 the hit Danish TV series Borgen brought Denmark’s questionable relationship with neighbouring Greenland to European living rooms. Danes don't know anything about Greenland at all, it showed. Despite highlighting continuing colonialism, the theme’s very presence suggested that Greenland is beginning to make an impact on Danish culture. A look at the burgeoning Greenlandic film industry suggests otherwise. Over four days in Copenhagen I find myself on the edge of a fascinating culture which almost no-one outside Greenland actually takes an interest in.

Colonial stereotypes

From Copenhagen’s lively city centre to the increasingly deserted alley leading to the North Atlantic centre in the east of the city: the closer I get to the Greenlandic film festival, the more dismal the neighbourhood of Christianshavn seems. Three friendly, mildly intoxicated homeless people are taking shelter from the gnawing wind. In broken English one of them, a man in his thirties, helps me count out the change for the street magazine he is selling before cheerily waving me on my way. All three share the same dark colouring and fine features.

Read 'CIA in Greenland: story about a polar whodunit' on cafebabel.com

These are the visible Greenlanders in Denmark, Ivalu later tells me. The graphic designer is one of 18, 000 first to third generation Greenlanders living in mainland Copenhagen, according to a 2007 study by the Greenlandic parliament. Not unusually she has a Greenlandic mother and a Danish father and is highly educated: we toast to her becoming a CEO the afternoon we meet. Ivalu spoke Greenlandic until she went to kindergarten but afterwards only spoke Danish, having to painstakingly relearn Greenlandic as an adult. That's fairly typical for her generation. Greenlanders learn all about Denmark at school. They have a hybrid identity of being both Danish and Greenlandic. Language-wise it's a bit more complicated as different political moods have favoured different education policies. The fact that Ivalu’s co-patriots sheltering in the metro, a social group thought to make up 10% of Greenlanders in Denmark, remain the prototype of the Greenlander for most Danes is a testament to the country’s lingering colonisation of an Arctic island almost 4, 000 kilometres from its shores.

Greenlandic cinema since 2009

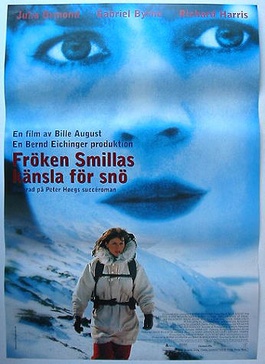

After three centuries of Danish rule Greenland gained home rule in 1979. It has self-governed in judicial affairs, policing and natural resources since 2009, a step which may lead to independence at some point in the future. Accompanying this political ‘revolution’, as former actress Vivi Nielsen calls it, has been its quieter sibling: a move towards cultural self-identification. Narratives about Greenland have remained few and far between, most notably Danish author Peter Hoeg’s novel-turned-film Miss Smilla’s Feeling For Snow. Despite Hoeg’s uncompromising criticism of Denmark’s exploitation and ignorance of the northern nation, his 1992 novel inevitably falls into the trap of exoticising Greenland’s more ‘authentic’ way of life – and even so one of the book’s few Greenlandic characters is an alcoholic. ‘Being a Greenlandic actor in Denmark is difficult,’ Vivi admits as we sit in Copenhagen’s Greenlandic house, hidden off a side street in the city centre. ‘You always get given the same parts.’

After three centuries of Danish rule Greenland gained home rule in 1979. It has self-governed in judicial affairs, policing and natural resources since 2009, a step which may lead to independence at some point in the future. Accompanying this political ‘revolution’, as former actress Vivi Nielsen calls it, has been its quieter sibling: a move towards cultural self-identification. Narratives about Greenland have remained few and far between, most notably Danish author Peter Hoeg’s novel-turned-film Miss Smilla’s Feeling For Snow. Despite Hoeg’s uncompromising criticism of Denmark’s exploitation and ignorance of the northern nation, his 1992 novel inevitably falls into the trap of exoticising Greenland’s more ‘authentic’ way of life – and even so one of the book’s few Greenlandic characters is an alcoholic. ‘Being a Greenlandic actor in Denmark is difficult,’ Vivi admits as we sit in Copenhagen’s Greenlandic house, hidden off a side street in the city centre. ‘You always get given the same parts.’

There is a light across the bridge; inside the candle-lit loft, a fairly typical arthouse crowd gather with anticipation for the booked out screening of the latest film to come out of Greenland, Shadow In The Mountains (‘Skygger I feldet’ or Qaqqat Alanngui, 2011). Popcorn has been replaced by glasses of wine. Students mingle with middle-aged women, and at least half of the people hastily taking their seats are Inuit. The general hush is broken by laughter and shrieks.

Greenland is beginning to tell its own story, with a growing film scene emerging on the island of 55, 000. The first tentative steps were made in the 1990s with Greenlandic-Danish collaborations such as Heart Of Light (‘Qaamarngup uummataa’, 1998), but it wasn’t until 2009 that Greenlandic film really took off, drawing international attention on the way. The milestone was A Man from Nuuk (‘Nuumioq’) by Greenlandic director Otto Rosing and Danish director and screenwriter Torben Bech, which was enthusiastically promoted as the first feature film entirely produced in Greenland. Rosing hoped to present a more honest depiction of Greenland to Denmark, somewhere between the homeless alcoholic and the igloo-dwelling eskimo. The Danish crew worked with amateur actors and Greenlandic youth so as to bring to Greenland the knowledge and skills to build up a film industry. Incidentally tonight’s film, in which a group of teenagers spend a weekend on an island in Greenland, boasts an entirely Greenlandic cast and crew.

Danish audience absent

Reactions from Danes and Greenlanders alike are tepid when I ask about the film. ‘It’s just a Hollywood chick flick set in Greenland,’ half-Greenlander Pauli remarks disparagingly. However it seems the bogeyman from their childhood stories is alive, well and throat-cutting. Shadow In The Mountains is proudly touted as the ‘most popular film in Greenland ever’; the North Atlantic centre has offered three extra screenings to cope with demand. As the chattering audience disperses contentedly, it is almost possible to brush aside a Danish friend’s gloomy prediction that I will only find Greenlandic cultural projects in public libraries in Denmark. Then again, this is not a cinema but a converted loft with a projector screen.

This shouldn’t be surprising given that Nuumioq itself, despite the Danish director and crew, was never even released in Denmark. ‘Greenlandic films are just too local to make it here,’ says director Torben. Danes who come to Greenlandic events generally represent a minority with some connection to the island, agrees Vivi Nielsen. ‘To be honest, I just don’t care what happens over there,’ a Danish student tells me in a bar hours later, after hesitantly answering me about what the capital of Greenland is. The emerging shoots of Greenlandic film industry can pat themselves on the back for indirectly leading to Greenland’s first drama school to open in 2012. The Greenlandic talent who are emerging to tell their own story are still waiting for their Danish audiences.

This article is part of the third edition in cafebabel.com’s 2012 feature focus series on multiculturalism in Europe. Many thanks to Ulrik Borch and the team at cafebabel Copenhagen

Photos: main S.O.S. Isbjerg © Greenlandic film festival; Borgen © screenshot Borgen/ videos: Qaqqat Alanngui' trailer (cc) TumitProduction; 'Nuumioq' trailer (cc) qosikim/ both via youtube