Reviving Italy from the coma: interviewing Annalisa Piras, Director of Girlfriend in a Coma

Published on

"I think we are at the end of the track with Europe. Either we renew the social contract among countries or we go for disintegration. Which is why we are very excited about doing Europe in a Coma, because at this precise historic moment it is very important to raise awareness of what is at stake."

Annalisa Piras talks about how to wake Italy, and Europe, out of the coma

Girlfriend in a Coma (2012) by London based journalist and film maker Annalisa Piras and writer and former editor of The Economist Bill Emmott, focuses on how contemporary Italy has been lying in a coma for the past twenty years. It explores the deep routed problems of the country while, at the same time, looking at its successes and possible solutions for the future. Since the film a lot has happened, and Annalisa Piras discusses the film and her hopes for reviving Italy.

How did the idea for Girlfriend in a Coma come about? What was the inspiration behind the film?

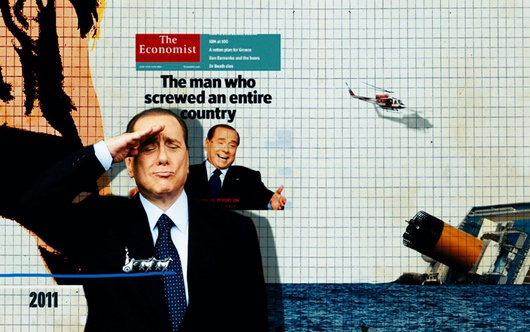

Well, Bill Emmott and I met in 2001 when Bill made the very famous cover of The Economist with Mr Berlusconi and the headline “Why this man is unfit to lead Italy”. We started a conversation on Italy and its many unresolved issues that have always seemed to come back in the same way over the past 20 years. So when Bill then wrote the book Forza Italia and the English version Good Italy, Bad Italy we discussed again how Italy seemed to be stuck in a timewarp, a sleep or paralysis unable to solve its problems. And so the idea rose that maybe it would be useful to make a film, because a film would allow us to reach a huge number of people and, at the same time, would also very robustly depict the situation that many Italians don’t want to see. So, the idea was that with a film, we might be able to help create more of awareness of this sort of sleep or coma that Italy seems to be in since 20 years ago.

You’ve done a tour not just in Italy but also in the UK and throughout Europe, how has the film been received so far, how have you found the reaction of different audiences?

It’s been extremely interesting, this kind of following that the movie has created because you will remember that the first screening in Italy on February 13th was cancelled due to the decision of the President of the MAXXI Museum in Rome where the screening was booked. That moment was seen by many as a form of censorship because the justification was that you shouldn’t screen a film that talks about politics in a public institution before the election. Since then, it has created a really strong following especially among students, which was very rewarding for us because we were hoping somehow to reach the younger generation, the people who know the seriousness of the situation and want to do something about it. So it has been very, very beautiful and it has filled us with pride to see these spontaneous screenings organised everywhere in Italy. We’ve tried to go to as many as possible, we’ve been so far to 45 but there has been as many organised independently, people getting together to watch the film and debate the issues in a kind of participatory campaign to analyse why the issues raised in the film are not part of the national debate. The stark contrast has been between spontaneous civic society embracing the film and the complete indifference of the institutions, the political world and the mainstream media.

It’s been extremely interesting, this kind of following that the movie has created because you will remember that the first screening in Italy on February 13th was cancelled due to the decision of the President of the MAXXI Museum in Rome where the screening was booked. That moment was seen by many as a form of censorship because the justification was that you shouldn’t screen a film that talks about politics in a public institution before the election. Since then, it has created a really strong following especially among students, which was very rewarding for us because we were hoping somehow to reach the younger generation, the people who know the seriousness of the situation and want to do something about it. So it has been very, very beautiful and it has filled us with pride to see these spontaneous screenings organised everywhere in Italy. We’ve tried to go to as many as possible, we’ve been so far to 45 but there has been as many organised independently, people getting together to watch the film and debate the issues in a kind of participatory campaign to analyse why the issues raised in the film are not part of the national debate. The stark contrast has been between spontaneous civic society embracing the film and the complete indifference of the institutions, the political world and the mainstream media.

Well, when the film was made Mario Monti had been elected after Silvio Berlusconi stepped down amid scandal. Since then we’ve had the disastrous election which lead to a long stalemate and now finally the appointment of Enrico Letta as PM. A lot has happened, but can we say that Italy is waking out of the coma?

It depends pretty much on who is watching. It’s a typical case of whether the glass is half full or half empty. A lot has happened since we made the film. A lot of positive things have happened, notably there is a strong sense that the public opinion in Italy is demanding change. Even if it was not the best political solution the fact that someone from outside the political class, someone like Beppe Grillo has got such a success at the elections... it is not a good thing in absolute terms because there are a lot of issues with the Movimento Cinque Stelle, [but] it has sent a strong signal that at least a third of voters in Italy demand a radical change. On the other hand, there are a lot of worrying symptoms that suggest the coma is getting worse. Particularly the electoral success of Silvio Berlusconi has been a bad blow to those who thought somehow the Berlusconismo era was finished.

In the film, you look at the Mala Italia and Buona Italia. In the first part, bad Italy, you look at issues such as corruption, political culture, and organised crime with figures guiding us through the chapter. But was there a little too much emphasis on Silvio Berlusconi? Is he the cause or a symptom of Italy’s problems?

In the film, you look at the Mala Italia and Buona Italia. In the first part, bad Italy, you look at issues such as corruption, political culture, and organised crime with figures guiding us through the chapter. But was there a little too much emphasis on Silvio Berlusconi? Is he the cause or a symptom of Italy’s problems?

Many people thought there was too much space for Berlusconi when they saw it before the elections, because many people hoped that Berlusconi was gone, there was this sense that he belonged to the past. But this was not the case, and so somehow Berlusconi had sadly the right place in the film. I think that too often many Italians have liked the idea of saying that Berlusconi was the cause of all evil, but actually Berlusconismo is a symptom, a symptom of fundamental problems with Italian democracy. Certainly a lack of grown-up political culture is what has allowed someone like him to dominate politics for the past twenty years. So the fact that someone who openly displays a sense of disregard for the institutions and for the state gets such a significant share of the vote is part of the problem. With or without Berlusconi, this disregard for legality is a problem that existed before Berlusconi, and so as well has the problem of selling and rigging votes, and the influence of organised crime on the results of the vote. Those are very old and pernicious issues of Italy that Berlusconismo has made worse.

It was interesting that when Mario Monti was nominated to be the technocratic Prime Minister after Berlusconi resigned, he had a very good track record in Europe and some Italian commentators said that he could be good for Italy. Is there more faith when someone else does the choosing?

There is a very important question. Now I think there is a deep awareness that the leaders that are produced by the traditional political parties, they end up making a mess. So there is this sense that when things get really serious, you need to call a technocrat because you cannot trust Italian politicians with serious matters. It was interesting that when Mario Monti was nominated, there was a big misunderstanding especially in Britain; with a lot of people saying this was undemocratic. But, first of all, the Italian system allows the President of the Republic to nominate who he wants as long as he is a member of parliament, and Monti was a senator, and then Parliament approves him and has a vote of confidence in him. So that was in line with Italian democratic practices. But secondly, there was a also a misunderstanding of what the Italians were thinking themselves because most Italians were very happy and pleased that [President of the Republic Giorgio] Napolitano chose a serious professor. So there was some kind of public approval of the choice of nominating Mario Monti, because people felt we needed someone serious and even though he wasn’t directly elected he had a lot of authority and respect. It’s all part of this issue with Italian politics that it’s a not a mature democracy, and political parties have little respect and credibility.

There is a very important question. Now I think there is a deep awareness that the leaders that are produced by the traditional political parties, they end up making a mess. So there is this sense that when things get really serious, you need to call a technocrat because you cannot trust Italian politicians with serious matters. It was interesting that when Mario Monti was nominated, there was a big misunderstanding especially in Britain; with a lot of people saying this was undemocratic. But, first of all, the Italian system allows the President of the Republic to nominate who he wants as long as he is a member of parliament, and Monti was a senator, and then Parliament approves him and has a vote of confidence in him. So that was in line with Italian democratic practices. But secondly, there was a also a misunderstanding of what the Italians were thinking themselves because most Italians were very happy and pleased that [President of the Republic Giorgio] Napolitano chose a serious professor. So there was some kind of public approval of the choice of nominating Mario Monti, because people felt we needed someone serious and even though he wasn’t directly elected he had a lot of authority and respect. It’s all part of this issue with Italian politics that it’s a not a mature democracy, and political parties have little respect and credibility.

In the film, you look at the issue of l’ignavia or sloth, namely the idea of being apathetic from the political process, unwilling to take a stand. But that’s not just a uniquely Italian thing though, isn’t this arguably a problem across Europe and across the western world?

Yes, it’s a huge problem of all our democracies of the western world. In this sense, we were very keen that the film would not be seen only as ‘these Italians, they’re always in trouble’ because the issues that we wanted to highlight are common to other democracies. And the sloth, the lack of personal responsibility and the lack of courage to act is something that is very widespread in Europe. Why is that? I think that since the fall of the Berlin Wall and the so called death of ideologies, people have found it very difficult to believe in a cause and engage themselves. So they have become more cynical and detached from the entire political process, which is a disaster because exactly at the moment that people stop believing in politics, that is when politics is allowed to deteriorate even further. There was a sense that this is a big problem in Italy, but it’s a shared problem with other western democracies and we need to fight it.

Moving on to the Buona Italia, you use some interesting examples of how civil society and communities can lead a reawakening. You also look at Italian businesses such as Ferrero and FIAT, how can Italian companies help lead the way?

Moving on to the Buona Italia, you use some interesting examples of how civil society and communities can lead a reawakening. You also look at Italian businesses such as Ferrero and FIAT, how can Italian companies help lead the way?

The thing about Ferrero, and the reason why we put them in the film, is because it seemed to us that they represent a form of enlightened capitalism that cares about the community in which it operates and thinks about the long term. So, in that sense, we thought it was a good model because it was clearly infused with Italian traditional values about family, solidarity, community, the respect of the tradition of the territory. It seemed to us that that was something to be proud of, and to be promoted and proposed as something that Italians should go back to. Of course there is a kind of ideal aspiration, we are talking about values and they do not necessarily always translate into practical solutions. Having said that, the spirit of community and the respect of the territory is something that could help Italy, notably in areas in the South where the aggregation of cooperatives like we have seen in the film the Cangiari project http://www.cangiari.it/, and the GOEL group in Calabria http://www.goel.coop/, they are creating jobs, they are creating jobs for women and for young people based on a cooperative model that puts the values of solidarity , community and territory at the centre. Of course you’re not going to solve what is a structural problem, of a change of economic model in all of Europe through these small cooperatives, but it is quite an inspiring example of things that you can do rediscovering your values and traditions.

That’s true, but as you say the bigger issues mean that in Italy unemployment has rocketed (latest figures put it at a record of 40.5 per cent for people between 15 and 24 years old according to ISTAT, the national statistic office) so, what is the role of Italian youth and the role of the diaspora? As the director of Vodafone Italia said in the film the issue is not young people leaving but whether they come back or not, the "return ticket". So how can you reach out to the Italian youth that you don’t lose that whole generation?

That’s true, but as you say the bigger issues mean that in Italy unemployment has rocketed (latest figures put it at a record of 40.5 per cent for people between 15 and 24 years old according to ISTAT, the national statistic office) so, what is the role of Italian youth and the role of the diaspora? As the director of Vodafone Italia said in the film the issue is not young people leaving but whether they come back or not, the "return ticket". So how can you reach out to the Italian youth that you don’t lose that whole generation?

That was one of the hopes of the film that somehow it would be seen as a call to arms for all those who have left. It is difficult to imagine a structured way of organising this enormous community that is growing oversears every day. But certainly what we thought could happen is that this huge community of talented young Italians who are now abroad could connect with the people who want to change Italy from inside and create a positive synergy in adding the pressure from outside to the pressure from inside and encourage people who want change. I think there are a lot of positive energies in Italy but they are very often isolated or discouraged or not connected with other like minded groups.

One thing we are doing with our website www.girlfriendinacoma.eu is creating a map of organisations inside and outside Italy to allow them to connect because the great thing that we are seeing in this moment is an increased online participation to the democratic processes. So this could be one way of reigniting some hope and some active engagement of people. We are also creating with Bill Emmott a foundation called the Wake Up Foundation because we have seen that there’s so much work to be done in continuing the conversation that we started with the film and so with the foundation we will try to keep raising awareness and connecting people. We also want to involve all the people who love Italy and who study Italy from outside. We want to keep increasing the critical mass, to keep the initiatives going. We are also producing a new film, Europe in a Coma, to continue that reflexion on the fact that in Europe we all have the same problems and we need to work together because the tiredness of our democracies is a common problem but to reenergise it and renew it, we need to unite forces and tackle the problem together.

So finally on a European level, with the economic crisis can Europe and the EU be seen by young people as a hope or hindrance?

I think we are at the end of the track with Europe. Either we renew the social contract among countries or we go for disintegration. Which is why we are very excited about doing Europe in a Coma, because at this precise historic moment it is very important to raise awareness of what is at stake. Certainly, the technocratic European Union has been for too long at the centre of the discourse on Europe. Which is why we need to bring back a Europe of the people, the Europe of cultures and identities and the idea of how much we have been always intertwined in both history and culture. I think that we need to rebuild that awareness of our common destiny and that to link it together we can be stronger, so the idea of solidarity and prosperity and security of the people coming together that’s something that needs to brought back into the mind of people because when in a family you start talking only about money and debt that’s the end of the family. We need to start talking with each other again and rediscover why what unites us is much more important than what divides us today.