Remember, the Council of Europe is not part of the EU

Published on

Translation by:

Cafebabel ENG (NS)The Strasbourg-based organisation defends human rights in Europe and needs to combat its dwindling visibility

‘It’s almost revolutionary.’ Matjaž Gruden is referring to the Council of Europe Convention on Action against Trafficking in Human Beings (CETS N° 197), the first European treaty of its kind which came into force on 1 February 2008, after many years under the ratification process of the 47 member states. The Slovenian, sitting proudly behind a modern wooden desk in his office, is the spokesperson for the Council of Europe in Strasbourg, eastern France.

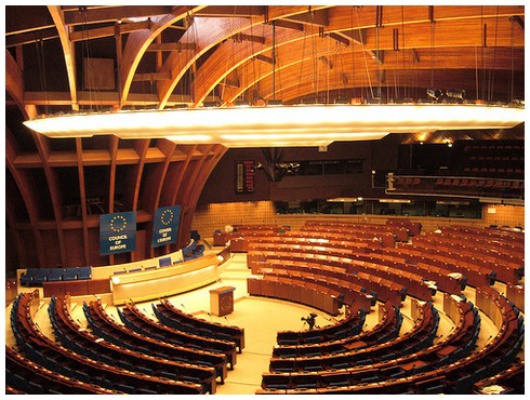

The everyday citizens outside this highly secure building complex are largely unaware of this little revolution which Gruden is so passionate about. People on the ground find themselves directly confronted with the security methods at the building’s entrance. Take off your jacket, put your metallic objects in a box - it feels like airport security. It’s not easy to get authorisation to enter the fortitude of the Palace of Europe, where the Council of Europe is located. It’s hard to navigate yourself with no building plan.

Welcome to the Council of Europe. This European lung was created in 1949 with 47 member states whose fundamental principles – democracy, human rights and the quality of life – are indispensable in Europe. But it often suffers from an inferiority complex with respect to the supranational blood circuit in Brussels. It means that their decisions don’t always have a direct effect – one of their major problems. Nevertheless, their complementary work does achieve change in the fundamental fields of economics and society, such as this latest Convention on Action against Trafficking in Human Beings – a silent revolution.

Welcome to the Council of Europe. This European lung was created in 1949 with 47 member states whose fundamental principles – democracy, human rights and the quality of life – are indispensable in Europe. But it often suffers from an inferiority complex with respect to the supranational blood circuit in Brussels. It means that their decisions don’t always have a direct effect – one of their major problems. Nevertheless, their complementary work does achieve change in the fundamental fields of economics and society, such as this latest Convention on Action against Trafficking in Human Beings – a silent revolution.

No clear plan in sight

Essentially, the Council of Europe lacks a clear profile, according to Matjaž Gruden. The historical reasons for this are its many similarities to the European Union, which is it separate from. In return, the spirit of competition should also be abandoned with this other organism. On a psychological level, the Council of Europe’s problem is coming second and being displaced by Brussels, and losing the importance that it had even in the sixties still.

Moreover, Strasbourg has a problem with its location, explains Micaela Catalano. The head of communications in parliamentary assembly describes it having one of the worst transport connections in comparison with other political centres. Another issue is the fact that hardly any press conferences take place there. And in general, the international press doesn’t speak much about what takes place in the Alsatian capital. Ironic, as the media is the only way news can be spread from Strasbourg. So it’s no wonder that little is known about the Council of Europe. Budget problems further mean that activities within the internal press department of the Council of Europe are limited. At the very least, press manager Alun Drake points to www.coe.int, the Council of Europe website, which offers various information and archives – perhaps too much.

Move closer

Coupled with a little budget and a lack of visibility and transparency, the Council of Europe has some hurdles to overcome. This is all despite the fact that it poses an enormous potential of specialised experience and influence, says Matjaž Gruden: ‘A few years ago the biggest NGOs in the field, such as Human Rights Watch (HRW) and Amnesty International (AI), agreed that the Council of Europe was the only international organisation which was influential with human rights in Russia.’

Nevertheless, it seems that that is of little help outside the system, who find that the Council of Europe is like a big jungle thanks to its complexity. Communication strategies need improving so that the important and relevant themes are highlighted, so visitors can actually see what the current activity actually is. Incidentally, not many of them head towards the palace of Europe, and no wonder; the European institutions themselves stand in the north-eastern outskirts of the city.

Nevertheless, it seems that that is of little help outside the system, who find that the Council of Europe is like a big jungle thanks to its complexity. Communication strategies need improving so that the important and relevant themes are highlighted, so visitors can actually see what the current activity actually is. Incidentally, not many of them head towards the palace of Europe, and no wonder; the European institutions themselves stand in the north-eastern outskirts of the city.

At the exit, the colourful flag of the 47 member states, that the Council of Europe shares with the EU (in the name of European integration!), blows in the wind. A glance back at the blue placard with the white letters Conseil de l'Europe - Council of Europe - the watchman for European democracy. The wide ‘Avenue of Europe’ leads us back to the quaint little town centre. The cathedral comes back into sight after just a couple of kilometres, appearing in between narrow streets and pubs. The Council of Europe already seems far away.

In-text photos: Council of Europe parliament (Adanblang/ Flickr), entrance (Enno Dummer)

Translated from Europarat: Revolutionäre Intimität