Religion snoozes in Prague

Published on

Translation by:

Andrew BurgessThe Czech Republic is renowned as being a predominantly atheist country. Prague is no exception to this rule, even if religious beliefs still make up the laws of the town

63%. That is the percentage of Czechs who claim not to belong to any religion, according to a survey carried out by the Gallup Institute in 2004. For the European continent as a whole, this proportion is much higher.

In order to understand the evolution of religious thought in the Czech Republic, and more specifically in Prague, it would be better to consult a history book. In the beginning, everyone, or nearly everyone, was Catholic, the Church supported the monarchy and nobody asked questions. And so, in a climate of widespread corruption and with links to Avignon, the archbishop of Prague paid large amounts of taxes in the Middle Ages.

With this in mind, Jean Huss, priest and master of ceremonies, proposed recentralising the Church on 'the message of the Bible.' And as there was no escaping punishment for such a 'reform' before the days which would inspire Luther amongst others, Jean Huss saw the end of his days on a stake in Constance in 1415. Then under the Hapsburg dynasty, the country was subjected to a forced 're-Catholicisation.'

Yet those who shared the same believes as Huss, the Hussites, had already taken over many communities across the country.

Tolerant Prague through its dark days

Prague was also influenced by Judaism. 'It was Ibrahim Ibn Ya'kub, a Spanish Jew, who was the first to return to Prague,' recalls Charles Wiener, a former secretary of the Jewish community in Prague.

Prague was also influenced by Judaism. 'It was Ibrahim Ibn Ya'kub, a Spanish Jew, who was the first to return to Prague,' recalls Charles Wiener, a former secretary of the Jewish community in Prague.

From 1492, following the re-taking of Spain by the Catholic monarchy, the town saw the arrival of swarms of ‘Sephardi Jews’ fleeing the persecutions taking place in the Iberian Peninsula. Despite certain restrictions imposed upon them in terms of marriage, the Jewish community rapidly expanded before being liberated in the 18th century. 'The rapid expansion had its effect on a number of fields, notably in the period between the two wars. The Czechs were philosemites and the Jews that had integrated themselves in the society were at the point of being to able create a political party,' Weiner notes.

As proof of this influence, the towns’ synagogue, which is architecturally similar to the Alhambra in Granada, found itself at the heart of the town.

With the arrival of the Second World War, ‘tolerant’ Prague entered into the dark days. Before the arrival of Communism, the Nazis had decimated the Jewish community. 'The war lasted longer here because the Germans entered Prague in 1938,' Wiener remembers. 'Those who had chosen to join the international brigades did not return, a choice that certainly saved their lives. Today, only 3,000 Jews remain in the Czech Republic, and they are essentially concentrated in the capital,' he remarks.

Another calling

Once under the control of the Russians, the religious communities were placed under control. The population was forcefully instructed to stop believing in God. Restrictions on freedom and pressure on the religious leaders became more pronounced. It was at this moment, a priori hardly favourable to spirituality, that Islam made its unexpected entrance in Prague.

'Having opted for socialism during the Cold War, students from Arabic countries returned to the East in order to continue their education there. What a surprise that was for the Communists to see them pray numerous time a day,' explains a member of the Muslim community of Algerian origin, who has lived in the capital for a long time.

This exception should not hide the reality though: under the Communist regime, theology students were begged to find another vocation.

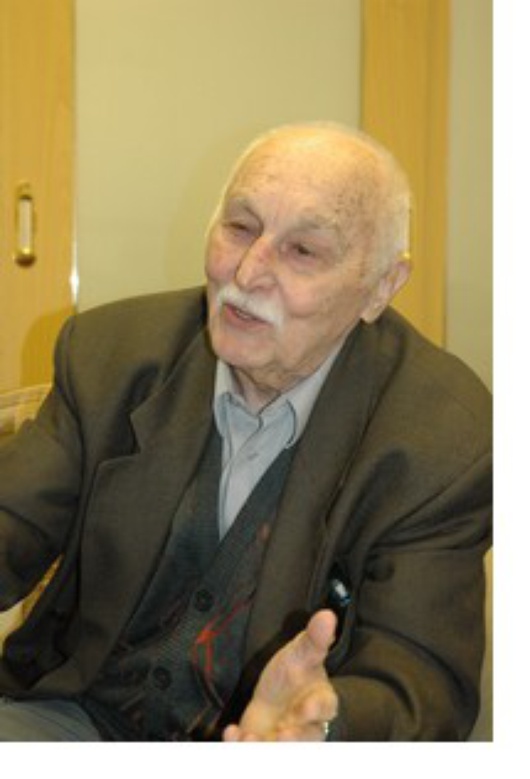

Milan Salazka, 79, recalls that it 'wasn’t possible to exercise your faith. Religion was forbidden for the party members, just as it was for those working with children.' For thirty years the churches remained empty, and the practising intellectuals left the country. 'The Christians were neutralised by the Communist community. All religious affairs were dealt with by the cultural minister,' the theology professor explains.

Milan Salazka, 79, recalls that it 'wasn’t possible to exercise your faith. Religion was forbidden for the party members, just as it was for those working with children.' For thirty years the churches remained empty, and the practising intellectuals left the country. 'The Christians were neutralised by the Communist community. All religious affairs were dealt with by the cultural minister,' the theology professor explains.

For the young people, a feeling shared

The Prague Spring of 1968 resulted in a large change in the rules. Christians and Communists entered into a modus vivendi agreement, allowing them to live alongside one another.

With the fall of the Berlin Wall, religious communities breathed again. From 1991, churches found themselves reunited with their rights, such as celebrating marriage. The existence of religion retook its roles within the pillars of society, be it in chaplaincies or in schools. A 'mini-community' of Muslims reappeared in the city with around 10, 000 members.

Vladimir Sanka, who converted to Islam at the age of 35, is president of the Islamic Foundation in Prague. He is delighted that visits to the mosque are organised on a regular basis. 'Since 2002, school children have been coming to prayer sessions on Fridays which are translated into Czech. The feedback is very positive, and the students are discovering the places that make up our religion.'

In February 2007, a Eurostat census revealed 59% of its population are atheists, 27.7% Christian, and a little more than 1% Protestant. Amongst the young people, the rejection of religion is still often very strong, like for a law student who says: 'my grandmother made me continue going to church - it was useless for me.'

While not totally rejecting its beliefs and respecting the right of others to live with their faith, he is angry with a 'church which has not known how to evolve with time and which is contradictory on quite a few things. The problem isn’t God, but religion!'

However practicing Catholic Lenka, 21, is the opposite. The student regrets that the 'mindset of the society is weakened and influenced by atheism.' She goes to Mass every Sunday, and considers religion a 'personal matter.' She is not impressed by the new Pope Benoit XVI. 'He lacks charisma. I am not sure that he is the right person at the right time,' she declares.

However practicing Catholic Lenka, 21, is the opposite. The student regrets that the 'mindset of the society is weakened and influenced by atheism.' She goes to Mass every Sunday, and considers religion a 'personal matter.' She is not impressed by the new Pope Benoit XVI. 'He lacks charisma. I am not sure that he is the right person at the right time,' she declares.

Protected today by the state, religious minorities continue to hold quiet days in a protective anonymity. For Wiener, 'the majority of Czechs are not atheist, but agnostic. It is about a lack of knowledge, not a rejection.' Professor Salazka, on the other hand, wants to be less pessimistic. 'At the moment religion is taking a nap. Czech society still lives with the scars of its past, but it will wake up one day.' If God wants it to.

In-text photos: Wiener, Milan Salazka, Lenka (FA)

Translated from Une histoire religieuse marquée au fer rouge