Refugees and ‘fællesskab’ in Denmark: tales from Sandholm camp for asylum seekers

Published on

Denmark was one of the first countries to adopt the UN refugee convention in 1951. We meet refugees from Kuwait, Iraq and Syria living at an accommodation centre north of Copenhagen, which has been run by the Red Cross since 1986

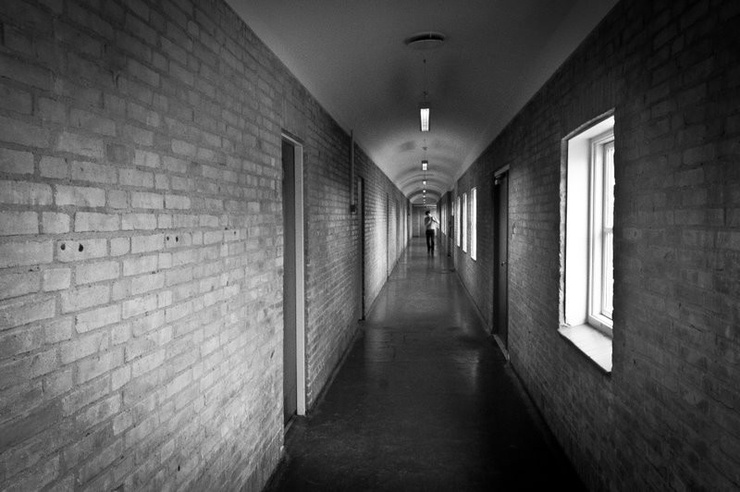

How do you count happiness? A group of surveyors asked people on a scale of one to ten. From this, the Danes were found to be the happiest in the world, with wealth, equality, comfort, functionality and a strong awareness of people’s capacity to change the world in which they live. They are united by fællesskab – the ideal of a community bound in togetherness by common values. However Center Sandholm, one of two centres located in the Copenhagen area, is a lonely outpost for refugees in Denmark.

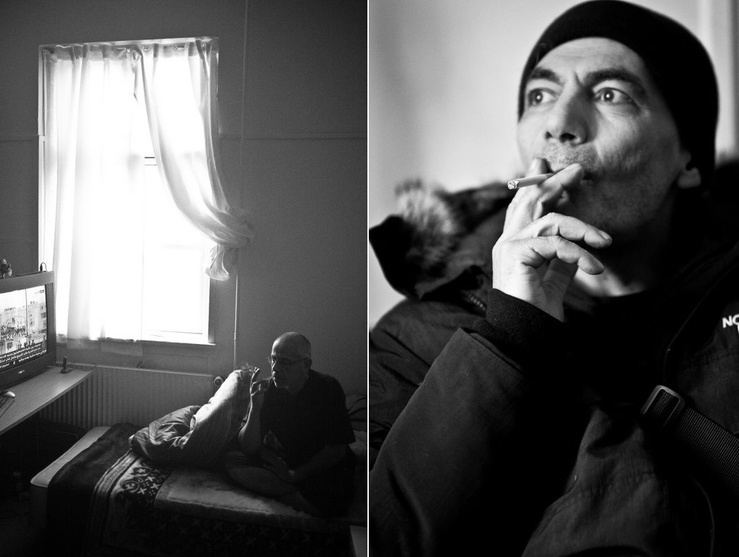

Cigarettes and Carlsberg

Sandholm's press department kindly insist we don't describe Sandholm as a prison: 'The politically correct expression for Sandholm is a reception and departure centre,' they say. The former army camp houses 600 refugees and immigrants from around the world. From the airport they proceed here alone. Some foreigners are brief arrivals while they wait for their asylum application to be processed. Others are sent here prior to being deported by the national aliens division. Another smaller group are trapped in bureaucratic purgatory. 'It’s like psychological torture,' says Talib al-Ansari, an Iraqi who has been at in the camp for 5 years. Iraqis make up the largest group of unsuccessful asylum seekers in Denmark. In 1979, Talib was kicked out of his homeland by Saddam Hussein’s government because his father was a shi’a activist. After living in revolutionary Iran without papers, he came to Europe. ‘At least in prison you know when you will be let out,' he says. 'Here you sit in your room, you wait for a letter, but nothing comes. No work. No life.’ Talib speaks with coherence and lucidity, but his face is filled with a tranquilised sadness. His clothes are rough like a man who gave up attending to his appearance.

Ali al-Jarrah, a 'resident' at Sandholm for twelve years, sits crosslegged on his bed wearing his cigarette smoke like Picasso. He is one of the stateless (bidoons) of Kuwait, a population of Arabs that the Kuwaiti government refuses to grant citizenship to. Do they have a place to pray? Ali pulls out a Carlsberg and laughs. In the bleak courtyard outside his window is a flagpole rattling in the wind and topped with the little red cross. Like Talib, no country will take him. 'Maybe because they have the power over me,' he muses. The Danish red cross has run the camp for 20 years, contracted by the democratically-elected Danish government. ‘I hate them. I rename them the Black Cross. They won’t give me my freedom. It poisons me inside.’ However the Danish red cross, which has run the asylum centre as an operator for the state and immigration authorities since 1985, doesn’t set the policy that has exiled Ali and Talib in Sandholm. Both resent being patronised by the impersonal charity of the Danish state. They are not allowed to work or live outside the camp. They are given an allowance which they spend on cigarettes or alcohol. One of Ali's neighbours staggers in briefly, shirt unbuttoned, eyes glazed and failing to notice the presence of the outsiders, takes a bottle of milk and leaves.

From Syria to Sandholm

According to the UN, the civil war which began in Syria in March 2011 has already claimed 8, 000 lives and led to 25, 000 refugees (based on refugees who registered with the UNHCR). George Elia and Jamal Mahmoud Raji are two Syrian opposition activists who have not been at Sandholm for long. They passed through the hills of Idlib province into Turkey with the support of guerrillas in the free Syrian army (FSA). Once they entered Greece by boat, they got on a plane to wealthy northern Europe. George had fled from Aleppo, the country’s second city. Threatened by his local mukhabarat (secret police), he asks us not to publish his photo, fearing a reprisal on his family. Through the Aleppo’s christian community’s control on the flow of information, the regime filled the minority populations – christian and alawite - with terror at the prospect of sunni muslim fundamentalists taking over the country, imposing strict islamic law.

George asks us not to publish his photo, fearing a reprisal on his family

George (a christian) and Jamal (a sunni muslim) sit together perfectly content with Ali (a shi’a muslim) and us (miscellaneous) without recrimination or judgement. Before the crackdown, the wealthy middle classes justified support of the regime on the grounds that president Bashar al-Assad seemed more secular, modern, enlightened and hence more European, superior somehow, than the islamist opposition. The deepening brutality exposes this as a lie. In one video on their computers that they have smuggled from home, a member of the Amn al-Jaysh (military security) drives his boots into the ribcage of a young man on the floor of a disused building. One of his fellows films the carnage on a mobile phone, avoiding the face of the attacker. 'Who is your god?' asks the aggressor. ‘Bashar is my god,’ he continues, laying a photo of al-Assad on the floor in front of the man and telling him to kiss it. The broken man spits on the picture and receives a further beating. George and Jamal watch on as if the videos are nothing.

Happy Denmark?

Jamal and George have no complaints, except for the weather. They say that the Danes have treated them kindly and without any prejudice. Danish government policy explicitly opposes multiculturalism, taking the French model of integrating foreigners into universalist national values. It is unlike the British or Swedish model of multicultural assimilation and celebration of diversity. Yet when around 500 Syrians fled to Belgium in mid-February, their applications for asylum were not being processed owing to the 'unclear situation' in their country. Energy to change this world still flows through Jamal and George. It briefly energises the Iraqis who long lost that sense.

In between mothers and young would-be gangsters, a man sits down opposite me on the train back to Copenhagen from Sandholm. He is wearing a hard hat with viking horns of two footlong dildos veined and quivering before my eyes. I double-take at the weirdness. It’s an abrupt divergence between the realms of migrants in Sandholm and happy Danes jostling in fællesskab. In another Europe accepting of multiculturalism, the stateless joker Ali would have laughed along. In this one he remains alone in his comfortable cell, sipping his Carlsberg and watching the distant arab revolution unfold in a world apart on his television screen.

This article is part of the third edition in cafebabel.com’s 2012 feature focus series on multiculturalism in Europe. Many thanks to Ulrik Troille Smed and the team atcafebabel Copenhagen

Images: © Nicola Zolin for ‘Multikulti on the ground‘ Copenhagen' by cafebabel.com