Refugee Camp: language as precious as a residence permit

Published on

Translation by:

Kath Burns

Kath Burns

Besides the often arduous process of seeking asylum, there's another barrier refugees face on arriving in a country: the language. In Belgium, the challenge is twice as hard, since they're confronted with both French and Flemish.

At a camp in Brussels's Maximilian park, refugees are being given the opportunity to learn both French and Flemish. Since people have no way of knowing in advance which part of Belgium they'll be sent to after submitting their asylum application, the choice of lessons is free.

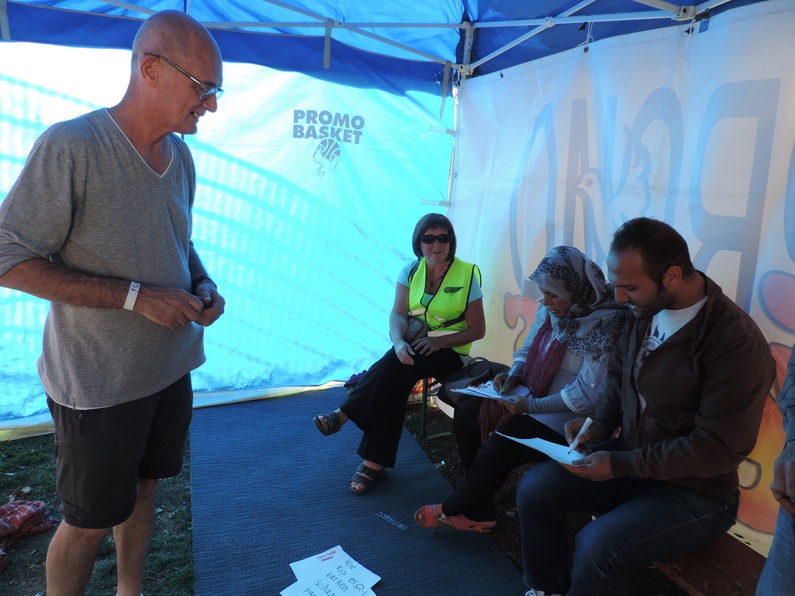

Tents have been set up as classrooms for the language lessons, using the limited means available. So far, all they contain is two benches, a makeshift blackboard and a few marker pens. The rest is a question of resourcefulness and imagination. Rather than a set programme, it's more about teaching the basics — the alphabet, numbers, telling the time, how to introduce yourself — and it varies depending on people's needs and moods. The result is a relaxed, if not somewhat freeform, style of teaching. But it's impossible to organise things differently. Despite the volunteers' efforts to set a precise time for the lessons, refugees tend to come and go throughout the day. The demand is constant and considerable, because refugees know they need to learn the language to get by in their host country. In these circumstances, how could the volunteers possibly refuse access to people who show up unexpectedly? So lessons are given almost constantly, even if it means repeating the same thing several times.

The lessons are given by a number of volunteers, who take turns. Nabil is one of them. As a French teacher, he's used to working with people who don't speak the language: "I've worked more with children. This is different. These are adults, and many of them have degrees, so they're already educated. I often work with children who've never been to school, so it's much harder. Just teaching them how to introduce themselves can take two weeks. But here, it's done in an hour. That said, there can be memory issues. People take in too much information in a very short space of time, and they won't necessarily retain it. So it doesn't hurt to repeat the same things often, at different points and with different teachers. Even if someone's already covered something, that allows it to really sink in."

The lessons are given by a number of volunteers, who take turns. Nabil is one of them. As a French teacher, he's used to working with people who don't speak the language: "I've worked more with children. This is different. These are adults, and many of them have degrees, so they're already educated. I often work with children who've never been to school, so it's much harder. Just teaching them how to introduce themselves can take two weeks. But here, it's done in an hour. That said, there can be memory issues. People take in too much information in a very short space of time, and they won't necessarily retain it. So it doesn't hurt to repeat the same things often, at different points and with different teachers. Even if someone's already covered something, that allows it to really sink in."

Lots of the refugees face the same difficulties. Most of the students — all of whom are men, with the exception of one woman — speak Arabic. Since some letters and sounds in our alphabet don't exist in theirs, it's particularly hard for them to distinguish, for example, between "Je" ("I") and "jus" ("juice"). And so the students patiently repeat the words, again and again.

More than just lessons

The volunteers' dedication can go a long way. Philippe, who deals with the Flemish lessons, had an idea while talking with a fellow volunteer: "We realised that it didn't make much sense to just make do with the lessons we have here. The ones learning French might eventually find themselves in Flemish-speaking Flanders, and vice versa. How will they cope? So we're planning to set up a crowdfunding site, to buy little books that the refugees can use to make themselves understood in all languages, even if they don’t know them. The books are only €5 – it doesn’t cost much to help someone integrate into society. We'll offer them to the refugees to make their transition easier."

The books they're buying are gems, and almost undoubtedly inspired by France's picture-filled Routard backpackers' guides, which allow you to make yourself understood anywhere in the world, without speaking a single word of the local language. Thanks to the books, Flemish and French will pose less of a problem for asylum seekers when they arrive at their designated welcome centre, and it gives them more time to learn the language.

The books they're buying are gems, and almost undoubtedly inspired by France's picture-filled Routard backpackers' guides, which allow you to make yourself understood anywhere in the world, without speaking a single word of the local language. Thanks to the books, Flemish and French will pose less of a problem for asylum seekers when they arrive at their designated welcome centre, and it gives them more time to learn the language.

This wonderful initiative really demonstrates the atmosphere of the camp, where helping one another and showing solidarity aren't empty words, no matter what language they're spoken in. And despite what you might think, the teaching works both ways: "I'm revising my Arabic with them," says Nabil, laughing. "It's classical Arabic, so it's different, and sometimes I really struggle to understand them." These sorts of exchanges allow both sides to enrich themselves, and sometimes in unexpected ways — like a man of a certain age asking a female volunteer how to say "I love you" in French!

Translated from Camp de réfugiés : la langue aussi précieuse que le permis de séjour