RAW Tempel association: Kreuzberg’s new railway children

Published on

Once a poor part of Berlin during the late 1970s, today the combined region of Kreuzberg-Friedrichshain is a core cultural centre of the German capital. The area still suffers from a high unemployment rate and risks an increase of high-rise housing along the river, making it a hub of political and social activism

‘I've seen it all. The year-long negotiations, the failures and success stories. It's a part of what we do; it's our life,’ says Kristine Schütt, holding a packet of tobacco as she sits in a small office. We can smoke here? 'Go ahead,' the artist also known as Mikado replies. She holds her rolled up cigarette for long minutes, thinking about the story told many times before: Berlin’s resistance, gentrification, anti-capitalism, stances on tolerance, change and political activism, everyone fighting for their little space in heaven.

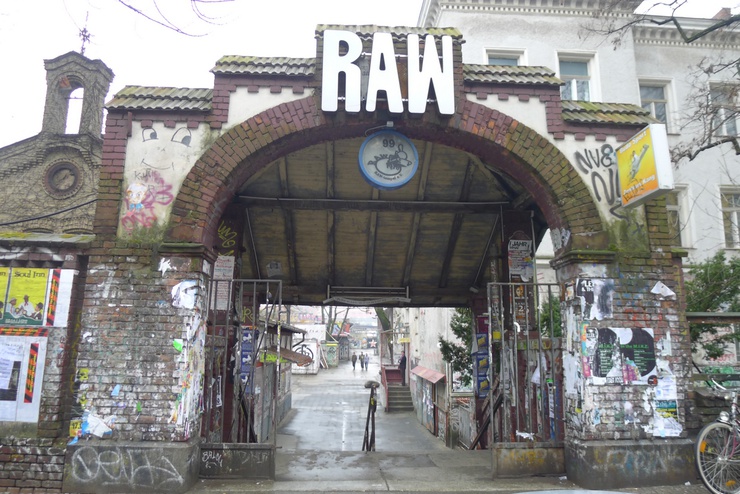

Kristine came to RAW Tempel ('national railroad repair works Franz Stenzer, ‘Reichsbahn Ausbesserungs Werk Franz Stenzer’), a national railroad maintenance works-cum-cultural centre, in 1998. Located in Friedrichshain in upper Kreuzberg, RAW (pronounced 'errahwee') Tempel has been one of the city's alternative hotspots in its 13-year existence. It is now home to 64 different projects related to music, the arts, flea markets, social and political activities, concerts, off-theatres and underground clubbing. ‘It's never been easy,’ she adds, before finally lighting up her cigarette.

From railway to ‘their way’

Colloquially known as 'X-Berg', Kreuzberg is bound by the river Spree in the east, and is located south of Mitte (city centre - ed). Up until the 19th century it was the rural heart of Berlin’s industry. During the second world war about 80% was destroyed. The derelict area became unattractive for investors but created a boom in cheap housing. In the huge immigrant wave that ensued students, artists and poorer citizens moved to Kreuzberg in the late 1960s to squat its old abandoned buildings.

Enclosed by the Berlin wall on three sides, it became famous for its alternative lifestyle, but the problems came after the fall of the wall. Kreuzberg suddenly found itself slap bang in the middle of the city. Its rents rose accordingly, and some parts became attractive residential prospects for the wealthy. ‘The government was not interested in sustainable city development and supporting the alternative scene, but in getting money into the city,’ says Kristine. ‘That's why lot of projects are forced to present a certain resistance.’ Different initiatives, social and political protests took place by the river Spree where there is a strong concentration of property for sale and rising rental prices for apartments.

When the railway tracks closed in 1994, it took four years before young people were moving in and swiftly making the abandoned tracks a cultural centre. ’There was no electricity, no water, nothing. Just an empty space for us to work,’ says Kristine. Once they got down to business in 1999, eventually the former railway company owners gave them a temporary contract for the four historical buildings in an area of 8.800 m2. As times changed so did the owners (Deutsche Bahn sold to a private company in 2007 - ed); ever since, the tenants have been fighting for a long-term agreement. Over the years, Kristine worked with children on music projects, and dedicated her time to fighting for the rights of people she now considers her family. ‘Investors are being put above the needs of citizens having free spaces and cultural possibilities,’ she continues. ‘Different initiatives are fighting for their right to stay and keep their rents reasonable.’

Political cultural zone

Neither the railway company nor mayor Franz Schulz were available for comment for this article, but Susanne Hellmut, a spokeswoman for the mayor’s green-Berlin party, explains the political support for continuing non-commercial projects withing RAW. ‘It is an important socio-cultural meeting point. Here, city development happens ‘from below’ and is in constant dialogue.’ Susanne confirms the party’s wish for RAW to ‘remain a low-threshold meeting point’ for neighbours, artists and athletes - a place where exchange, culture as well as good parties take place. ‘We have to do it by the book if we want to become true owners, get funding and finally focus on our projects,’ says Kristine. ‘We have to stay because we are an independent and self-organised cultural centre. It's important for this to mean something in this cruel political world,’ adds photographer Stefan Seifarth, who came to RAW Tempel in 2010.

'It's important for this to mean something in this cruel political world’

According to the German newspaper Die Welt, the capital only has a few available properties; the portfolio of property fund values it to only 693 million euros. One of the last jewels at the river Spree, near Ostbahnhof., is MEGASPREE. Created in 2009, this initiative calls for citizen votes on certain conditions concerning the urban planning of the river banks. The goal was to link long-term initiatives and cultural institutions to combine an alternative lifestyle. ‘Despite the voting majority of citizens in Friedrichshain-Kreuzberg, it turned out to be difficult to put these conditions into legal procedures, partly because the district has to follow the politics of the senate,’ says Kristine.

In spite of everything, the cultural scene in this area is rolling. ’When you live here, you chose to be active,’ claims Vanessa Drouet, 30, who moved to Berlin from France two years ago. ‘Politics is power but also passion, just like the passion we have in fighting for our rights. It’s good to think in a political manner. You just have to know how to use your tools smartly.’ The sense of artistic freedom and a right to do something that is respectful holds everything together. ‘Many people are still afraid and cannot see or organise the alternatives in a clever way, because they are not educated enough, don't have the tools, or differ too much ideologically,’ finishes Kristine. It is not possible to separate the fight for culture and open spaces from the fight against capitalism. Yet this story of a social struggle is not only typical for Berlin, but symptomatic of a much bigger development to protect society, like the global occupy movement.

This article is part of the sixth edition of cafebabel.com’s flagship project of 2012, the sequel to ‘Orient Express Reporter II‘, sending Balkan journalists to EU cities and vice versa for a mutual pendulum of insight. A huge thanks to the folks from cafebabel Berlin

Images: main and RAW buildings in-text © AK; three girls at Ladyfest party at RAW, 2007 (cc) Korbahar/ video (cc) TheRocknrollpictures/ youtube