Pulling a sickie

Published on

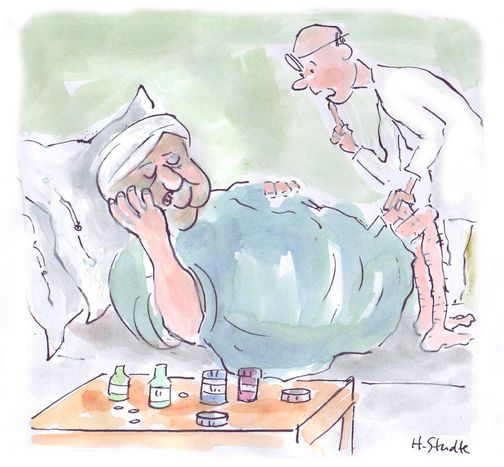

Whether through dishonesty, laziness or a touch of hypochondria, hoards of the European workforce take undeserved days off each year. Our vocabulary for the practice comes from French literature and ancient Greece

In May, the WHO raised the swine flu pandemic alert from level five to level six; the next day, the number of flu-related absences from work in the UK jumped 30%. The idea that the world is in the grip of an epidemic might encourage some to conclude the worst of that peculiar tickly feeling in their throat. Italians cut out a day when they fare sega  (make a saw). When the English stay at home it’s known as a duvet day

(make a saw). When the English stay at home it’s known as a duvet day , while Germans blau machen

, while Germans blau machen (make a blue). This comes from the expression ‘a blue Monday’; traditionally, German craft workers dressed in blue overalls and took Monday as their day of rest.

(make a blue). This comes from the expression ‘a blue Monday’; traditionally, German craft workers dressed in blue overalls and took Monday as their day of rest.

Hypochondria began in Europe. The term was coined by Hippocrates; ancient Greek physicians believed that the spleen (found under a bone named the hypochondria) was the source of various ailments. Much is blamed on the humble organ; in Polish, the sledziennik (spleen-er) is a rather depressed person who complains of many illnesses. In French, to have a spleen baudelairien

(spleen-er) is a rather depressed person who complains of many illnesses. In French, to have a spleen baudelairien (Baudelaire’s spleen) is to suffer from the melancholy described by the poet (he wrote four separate poems about existential angst, all named ‘spleen’).

(Baudelaire’s spleen) is to suffer from the melancholy described by the poet (he wrote four separate poems about existential angst, all named ‘spleen’).

When the Polish identify a case of chory z urojenia (patient with delusions), they’re making a literary reference to Moliere’s comedic play Le Malade Imaginaire

(patient with delusions), they’re making a literary reference to Moliere’s comedic play Le Malade Imaginaire (The Imaginary Invalid, 1673). In it, an old miser is convinced he is suffering from a number of illnesses, for which his doctors are happy to prescribe expensive treatments. The phrase is alive and well in French, and Italian commentators lament the damage done to the economy by malati immaginari

(The Imaginary Invalid, 1673). In it, an old miser is convinced he is suffering from a number of illnesses, for which his doctors are happy to prescribe expensive treatments. The phrase is alive and well in French, and Italian commentators lament the damage done to the economy by malati immaginari (imaginary invalids).

(imaginary invalids).

Deliberately conning the boss into granting a day off work is known in English as pulling a sickie . In Spain, someone who is telling tall tales might be accused of suffering from cuentitis

. In Spain, someone who is telling tall tales might be accused of suffering from cuentitis (story-itis). To invent elaborate lies in Polish is called odstawiac szopke

(story-itis). To invent elaborate lies in Polish is called odstawiac szopke  (making a Christmas crib) or odstawiac cyrk

(making a Christmas crib) or odstawiac cyrk (making a circus). Baudelaire and Moliere might be fondly remembered for their creative talent, but it seems that day-to-day fabrications are somewhat less celebrated.

(making a circus). Baudelaire and Moliere might be fondly remembered for their creative talent, but it seems that day-to-day fabrications are somewhat less celebrated.