Profiting from a crisis: Who is making money from the refugees?

Published on

Translation by:

Jack Cater

Jack Cater

Citizens are welcoming refugees into their homes, charities are reporting a record number of donations; the willingness of Germans to alleviate the crisis remains strong. However, companies are also jumping on the compassion bandwagon. Is this really out of empathy or due to ulterior motives? Who is really profiting from this crisis?

The refugee crisis continues to be ever-present in day-to-day life, whether it be on television, in newspapers, or on social media. Many companies have committed to helping the incoming refugees, from their point of arrival in refugee camps to their attempts to establish an independent life. The publishing house Langenscheidt Verlag, for example, supports refugees and workers with a fundamental problem: communication. At the end of August, the company made its Arabic dictionary available online for free.

“In the last few months, we have received lots of inquiries from refugee organisations and private initiatives,” explains Eckard Zimmermann, head of the digital business department, “learning German is an important part of integration.” The company wants to make communication with volunteers easier from the moment that refugees arrive to ensure that contact and trust will be immediately established: “Thus not a book, but a digital application,” he explains.

These suggestions came from social networks, which are playing a significant role in the crisis for both volunteers and the new arrivals: “For refugees, the smartphone is a gateway to the world. It is fascinating to see how quickly news of our work spreads,” Zimmermann states. For the publishers, it is important to support the refugees not only financially, but also through regular direct contact: “Through personal involvement, they learn that they are welcome and gain confidence.” In the coming weeks and months, the publisher will work on similar dictionaries in other languages, and develop a digital application that translates entire sentences from Arabic to German – again offering the product for free. Langenscheidt has worked hard to recognise existing problems and responded to suggestions from the community. Because the publishing house offers its product for nothing, in this case, there can be no talk of profiting from the crisis.

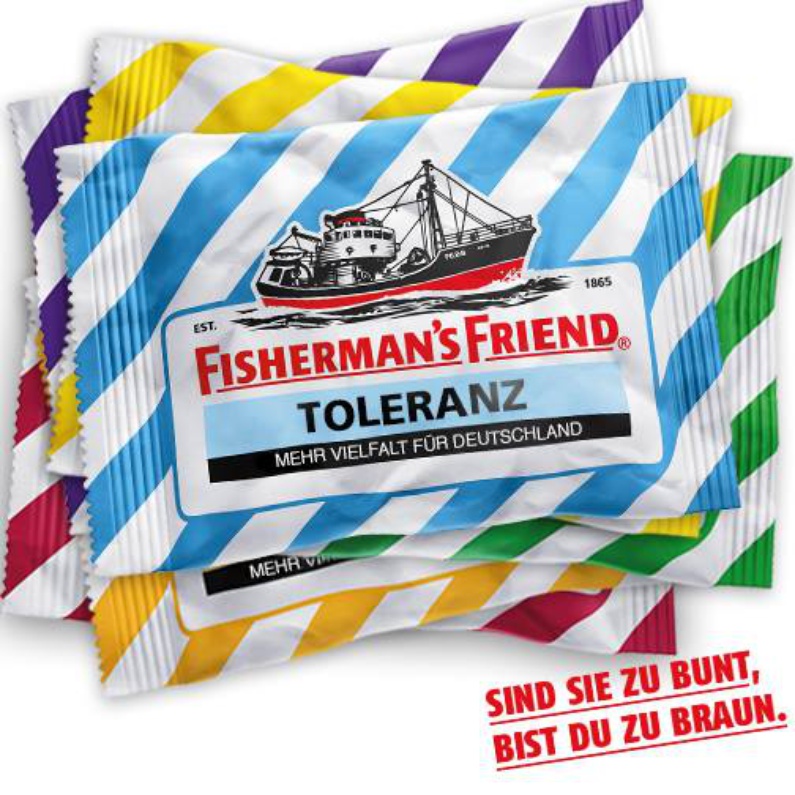

Other companies may not help directly on site, but clearly position themselves against right-wing opinion. The brand Fisherman’s Friend published a photo on its Facebook and Twitter pages on 27th August. The picture shows a colourful stack of the companies traditional packaging. In place of the sweet’s flavour, the packaging displays the inscription “Toleranz: mehr Vielfalt für Deutschland” (Tolerance: more diversity for Germany). In their social media publication, the company speaks directly to right-wing commentators: “Hey Heidenau and Co., just for you: our latest flavour. You should try it sometime.” So far the post has received 64,000 likes and has been retweeted 1,300 times. The company may well gain sympathy and support from this approach, but it's still the message of tolerance, rather than of profit, that takes the foreground.

This attitude cannot be taken for granted. Some companies use the refugee crisis to reap financial benefits, explains Stephan Lessenich, Professor of Sociology at the University of Munich: “We live in an economy that provides incentives for economic players to monetise all possible social needs,” he explains. If the act of jumping on the "refugees welcome" bandwagon seems profitable, that's exactly what these companies will do.

This attitude cannot be taken for granted. Some companies use the refugee crisis to reap financial benefits, explains Stephan Lessenich, Professor of Sociology at the University of Munich: “We live in an economy that provides incentives for economic players to monetise all possible social needs,” he explains. If the act of jumping on the "refugees welcome" bandwagon seems profitable, that's exactly what these companies will do.

These days, “refugees welcome” products are a real money-spinner. Since May, the number of Google searches for the term “refugees welcome t-shirt” has increased sharply. Between August and September alone, the figure doubled. Many smaller distributors sell their products, including these t-shirts, on Amazon. To sell on Amazon, the company charges distributors a 15% fee on the price of each item. In this way, Amazon profits from the “refugees welcome” campaign. Yet even if the sellers used their own platforms to sell their products, rather than Amazon, it is not certain that refugees would see any benefit from it. It's unclear how much money goes into the production of these products, and how much profit is left that could theoretically be donated to refugees.

Some shops try to confront the problem with a more transparent approach. The online shop “DirAction” is a small business that primarily sells products with anti-fascist themes. Its slogan is “dressed to misbehave”. On the site’s homepage, customers can read their so-named "solidarity initatives". A “refugees welcome” shirt is on sale here for 14 Euros. In the description, it is explained that 5 Euros from each purchase will be passed on to Lampedusa Hamburg. Lampedusa is a protest group made up of 300 refugees who have been fighting since 2013 for the permanent right to remain in Germany.

Also in Hamburg, a collective of 15 companies and labels have come together with the aim of providing aid to refugees. They call themselves “Moin Moin Refugees” and have mobilised to organise a big event. On 20th October, a festival will be held across six clubs in Hamburg, though the initiative is still a work in progress: “Regarding such an important and topical issue, it seemed obvious to mobilise as many people as possible,” the collective writes on Facebook. All proceeds from entrance fees, food and drink are to be used to meet refugees' urgent needs. The companies are working together with “Menschhamburg”, a not-for-profit organisation which coordinates material and cash donations for refugees in Hamburg. Entry costs 11.70 Euros online, with 10 Euros from each ticket going directly to the association. So far, 23000 people are attending the festival on Facebook. “None of the profits will go to us, that goes without saying,” the collective states. With no money earned by the company and a huge party being thrown for Hamburg, this project really is designed to help as many refugees as possible.

Also in Hamburg, a collective of 15 companies and labels have come together with the aim of providing aid to refugees. They call themselves “Moin Moin Refugees” and have mobilised to organise a big event. On 20th October, a festival will be held across six clubs in Hamburg, though the initiative is still a work in progress: “Regarding such an important and topical issue, it seemed obvious to mobilise as many people as possible,” the collective writes on Facebook. All proceeds from entrance fees, food and drink are to be used to meet refugees' urgent needs. The companies are working together with “Menschhamburg”, a not-for-profit organisation which coordinates material and cash donations for refugees in Hamburg. Entry costs 11.70 Euros online, with 10 Euros from each ticket going directly to the association. So far, 23000 people are attending the festival on Facebook. “None of the profits will go to us, that goes without saying,” the collective states. With no money earned by the company and a huge party being thrown for Hamburg, this project really is designed to help as many refugees as possible.

“Whether or not companies’ initiatives actually benefit the people they are meant to depends on the intelligence, creativity and persuasiveness of each particular initiative,” explains Professor Lessenich. It's possible, therefore, that helping refugees can backfire. The newspaper Die Bild is an example of this. The tabloid launched the initiative “Wir helfen” (We Help) and was able to convince high-profile politicians such as Vice Chancellor Sigmar Gabriel to pose with the official logo. The aim was to report on relief campaigns and collect donations. In mid-September, Bild made an agreement with every team in the first two divisions of the German football league, that all players would wear the “Wir helfen” logo on their shirts. It was designed to be a far-reaching act of solidarity with the support of a prominent national newspaper. However, when the Hamburg-based club St. Pauli distanced itself from the initiative, it was subsequently compared to right-wing parties by Bild’s chief editor Kai Diekmann. For other teams, this was going too far. They supported the Hamburg club. Nine more teams came out without wearing Bild’s logo. The initiative made quite an impression, but distracted from the real point of the exercise – to help refugees.

The paper was accused of using the refugee crisis to attempt to improve its image. Only a few months earlier, Bild had spoken of falling under an “asylum onslaught”. Lessenich claims that “it can be assumed that civic involvement is more durable and reliable than demonstrations of sympathy from commercial businesses, whose attention will soon turn towards other events when it seems profitable.”

The paper was accused of using the refugee crisis to attempt to improve its image. Only a few months earlier, Bild had spoken of falling under an “asylum onslaught”. Lessenich claims that “it can be assumed that civic involvement is more durable and reliable than demonstrations of sympathy from commercial businesses, whose attention will soon turn towards other events when it seems profitable.”

Translated from Profiteure der Krise: Wer verdient an den Flüchtlingen?