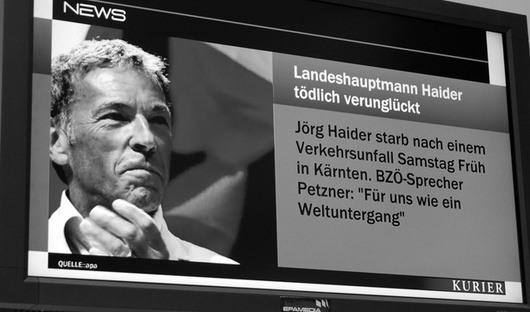

Press review: the European right after Jörg Haider's death

Published on

Following the death of the Austrian politician after a car accident on 11 October, the European press speculates on the consequences for coalition negotiations in the country. Haider's Alliance for the Future of Austria could now possibly reunite with the Freedom Party of Austria

‘A reunification of Austria's right-wing parties?’ - Die Presse, Austria

Jörg Haider's death could lead to a reunification of Austria's right-wing parties along the lines of the conservative CDU and CSU in Germany, writes Die Presse newspaper: ‘Without Haider the Alliance for the Future of Austria (BZÖ) is threatened with political insignificance both in its programme and in personal terms. There is only one chance for it to remain active outside Carinthia: continuing Haider's fight against 'the system' in his memory. In view of the increasing pressure for a grand coalition, this strategy stands a fair chance of success. In naming Haider's friend and spokesperson Stefan Petzner as his successor, the BZÖ is also concentrating on holding onto power in Carinthia, where Haider would have gone for an absolute majority in the next elections. Here the politician's appeal remains unabated even after his death. It is entirely possible that the call to reunite the right wing over Haider's grave will result in a widely-discussed 'CDU/ CSU' type solution’ (Michael Fleichhacker)

Jörg Haider's death could lead to a reunification of Austria's right-wing parties along the lines of the conservative CDU and CSU in Germany, writes Die Presse newspaper: ‘Without Haider the Alliance for the Future of Austria (BZÖ) is threatened with political insignificance both in its programme and in personal terms. There is only one chance for it to remain active outside Carinthia: continuing Haider's fight against 'the system' in his memory. In view of the increasing pressure for a grand coalition, this strategy stands a fair chance of success. In naming Haider's friend and spokesperson Stefan Petzner as his successor, the BZÖ is also concentrating on holding onto power in Carinthia, where Haider would have gone for an absolute majority in the next elections. Here the politician's appeal remains unabated even after his death. It is entirely possible that the call to reunite the right wing over Haider's grave will result in a widely-discussed 'CDU/ CSU' type solution’ (Michael Fleichhacker)

‘Haider was significant enough’: Dnevnik, Slovenia

Dnevnik newspaper publishes an obituary on its website: ‘In European terms Haider was neither a prominent political figure nor a nightmare. His legacy was rather the political discourse of the short-lived 'Third Camp' at the end of the last century. For Slovenia's relations to Austria, primarily in relation to the Slovenian minority in Carinthia, he was definitely a bone of contention. The real question now is whether Haider was significant enough to leave a void not only in Carinthia, but also in Austria.

'This void will perhaps soon be filled'

In any event, this void will perhaps soon be filled. It may be that a merger between Haider's former party, the Austrian Freedom Party, and the party he led up until his death, the Alliance for the Future of Austria, will form the last chapter in the biography of an eccentric with good relations to Gaddafi and Saddam Hussein, but to whom few doors were open in Vienna. The void in Carinthia will reflect Haider's true value’ (Dejan Kovac)

‘Haider was no nationalist’: Lidové noviny, Czech Republic

‘With the death of Jörg Haider, European right-wing populism has lost an icon. But it has not lost its appeal,’ writes the conservative daily. ‘What attitude should one adopt to a political force cultivated by Haider for a quarter of a century? All told, this populist movement received 28% of the vote in the last elections and could well participate in the next government.

'He was a demagogue'

It doesn't serve much purpose to put Haider into one basket with xenophobic neo-Nazis. Haider was no nationalist, but he was a demagogue. Even back in the eighties he had accused the government of not being pro-European enough. Ten years later he opposed Austrian membership in the EU. If you believe his opponents he appealed to the same voter groups that would have voted for Hitler in other circumstances. But the fact remains that there are such voters’ (Zbyněk Petráček)

‘Figurehead of the old ultra-right movement in Europe’: De Standaard, Belgium

The Belgian daily writes: ‘It is to Jörg Haider's credit that he broke up a rigid political system in Austria. He leaves behind a nation with a weakness for populism, xenophobia, old Nazi sentiment and isolationist policies. But for Europe's extreme right, too, in the end Haider's success was a mixed blessing. More than Le Pen in France or Filip Dewinter in Flanders, Haider became the figurehead of the old ultra-right movement in Europe.

But his short-sighted dream of a joint European ultra right-wing list soon shattered against the controversies and the fact that Haider attached more importance to his ego than political projects. The (ultra right Flemish) party Vlaams Belang, which on 11 October sent sympathy telegrams to Austria, broke its ties with Haider in 2005. All of a sudden the Vlaams Belang magazine started describing the man who it had hailed as a hero for years as someone who changed his views as often as he changed his shirt’ (Jom de Cock)

This press review is provided by