Poverty: searching for the state of emergency in Athens

Published on

Translation by:

Annie RutherfordWhile the ‘troika’ and the government continue to churn out new austerity measures, young people are revamping the image of their country and are putting a different face on poverty. A vision for Europe’s future?

In the current economic crisis, the word 'Athens' sets alarm bells ringing. Before my departure, a colleague jokes that I mustn’t forget to take my safety helmet. Friends who were recently in Athens speak of a revolution from below which is slowly growing and will soon break out. There’s something in the air, they say.

As we climb out of the airport shuttle bus at the infamous Syntagma Square, the epicentre of the anti-troika protests, we are hit by the gentle scent of orange blossom. It is spring in the Greek capital and city dwellers hurry across the bustling square in front of the parliament. In the anarchist quarter Exarchia the cafes and terraces are buzzing. A few shops have hit hard times or have closed down. Tourists’ voices aren’t heard here all that often these days. Even the police dare not go to Omonia Square after midnight anymore. However, the city’s main junction could be any large, uninspiring square in any big city. A few homeless people, a few beggars, a few prostitutes. Where, then, is the accursed crisis? Where is the state of emergency?

As we climb out of the airport shuttle bus at the infamous Syntagma Square, the epicentre of the anti-troika protests, we are hit by the gentle scent of orange blossom. It is spring in the Greek capital and city dwellers hurry across the bustling square in front of the parliament. In the anarchist quarter Exarchia the cafes and terraces are buzzing. A few shops have hit hard times or have closed down. Tourists’ voices aren’t heard here all that often these days. Even the police dare not go to Omonia Square after midnight anymore. However, the city’s main junction could be any large, uninspiring square in any big city. A few homeless people, a few beggars, a few prostitutes. Where, then, is the accursed crisis? Where is the state of emergency?

Every day we hear alarming new reports. The red cross hasn’t delivered this many food parcels to countries in crisis since the second world war. The Guardian shows us images of people reaching out to grab plastic bags of oranges. ‘Living as though in a warzone’, ‘Need, poverty, hunger: Greece sinks into misery’, read the headlines of the international press. To put it plainly, nothing but bad news is coming out of Athens. Welcome to a third world country - in the centre of Europe.

CRISIS PORN

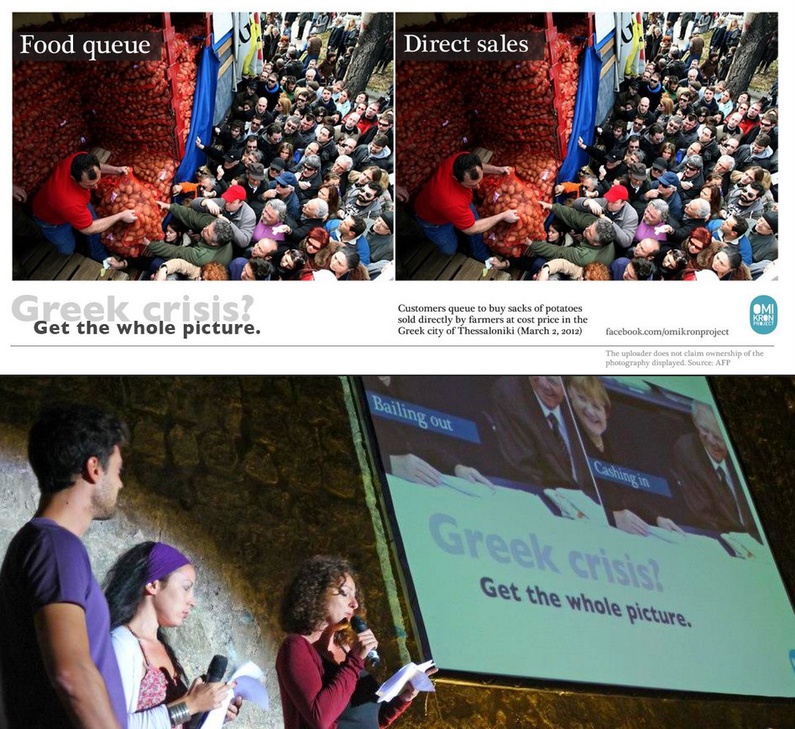

‘We call that crisis pornography,’ laughs Aggelos, 32, in the Omikron Bar, which sits on the corner of Syntagma Square. Today, a manageable group of ten people are making a proper racket. They are marking the suicide of the 77-year-old chemist Dimitris Christoulas, who took his life exactly a year ago. ‘We cannot leave our children with debt,’ he called out, before bidding a final farewell.

Ismini, Aggelos and a handful of young Greeks and Europeans are sick of this image of their country in crisis, the image of Greeks just drinking ouzo and bumming around. Why has Europe singled out Athens for a certificate of poverty? Why aren't Dublin or Madrid the scapegoats? With adverts, a blog and videos, the precarious creatives want to present an alternative image of their country and use social networks to provoke scrutiny abroad.

The project is called Omikron – named after the bar in which the first plans were forged. ‘We were sick of the endless discussions and wanted to actually do something,’ says Ismini, 30. ‘Yes, poverty and unemployment exist. But silence is never a solution,’ she comments, referring to the Greek media watchdog’s move to ban pictures of deprived people being shown on television without permission. ‘But we also want to tell you guys out there that we’re not alone here. Stop constantly rebuking this country, give us more time.’

The project is called Omikron – named after the bar in which the first plans were forged. ‘We were sick of the endless discussions and wanted to actually do something,’ says Ismini, 30. ‘Yes, poverty and unemployment exist. But silence is never a solution,’ she comments, referring to the Greek media watchdog’s move to ban pictures of deprived people being shown on television without permission. ‘But we also want to tell you guys out there that we’re not alone here. Stop constantly rebuking this country, give us more time.’

Generation ‘Working Poor’

With youth unemployment at 58%, uncertainty reigns amongst young Greeks. The trend is to get out and leave. The Greeks have to deal with shrinking salaries, higher insurance payments, a VAT hike from 19 to 22%, as well as higher taxes on alcohol, petrol and cigarettes, job losses in the public sector and cuts to pensions. Anyone with the necessary spare change and a touch courage abandon ship to seek their fortune elsewhere in Europe. However, the latest statistics from the eurozone are not pretty either: 2013 sees 12.1% of people across Europe without any income.

In the midday sun of Exarchia, job seekers Jenny, Giannis and Christos talk about how their generation is being left behind. Christos, 34, stands up and knits his brows as he rolls a cigarette. The filmmaker works as a freelancer and earns between 400 and 500 euros monthly. Is that enough to pay for health insurance and other basic needs? Pfff, he touches wood, ‘No one here in Greece has that.’ He had to go to the dentist at christmas – luckily a friend was able to help him out last minute.

He seems to be relatively relaxed about the fact that he lives below the official poverty line along with over a fifth of the Greek population. With a precarious job, irregular income and no form of social security, Christos belongs to the working poor, a diaspora which is putting down roots not only in Greece but all across Europe.

He seems to be relatively relaxed about the fact that he lives below the official poverty line along with over a fifth of the Greek population. With a precarious job, irregular income and no form of social security, Christos belongs to the working poor, a diaspora which is putting down roots not only in Greece but all across Europe.

Do they feel poor? ‘There are kids in schools who are undernourished – that’s poverty,’ says Giannis, a 28-year-old interpreter, shaking her head. ‘We’re all alarmed, but no one will die. We now have less and we have to get used to that. The trend is to get away from Greece. Or back to your family. Return to the nest. That’s the way we’re holding it together.’

ACTIVE CIVIL SOCIETY: THE OTHER FACE OF POVERTY

‘A large proportion of Greeks own property,' explains Alexander Theodoridis. 'So poverty isn’t necessarily visible on the streets. But you can sit in your own house and still be hungry.’ Aleander works for Boroume (‘We can’), an NGO founded in 2012 which connects soup kitchens in Athens with hotels, restaurants and bakeries which would otherwise throw away excess food. It’s one of many initiatives started by Athenian civil society, which has blossomed during the years of the crisis.

On the green square opposite Kallimarmaro, the first olympic stadium, you get the feeling that you’ve landed in Wes Anderson’s latest film, Moonrise Kingdom. Hundreds of boy scouts in dark blue, knee high socks and blue and white striped neckties are standing in a circle. ‘Strong Ostattika,’ they scream and symbolically raise their carved poles in the air in honour of their region. Ten mysterious boxes stand in the centre of the circle.

On the green square opposite Kallimarmaro, the first olympic stadium, you get the feeling that you’ve landed in Wes Anderson’s latest film, Moonrise Kingdom. Hundreds of boy scouts in dark blue, knee high socks and blue and white striped neckties are standing in a circle. ‘Strong Ostattika,’ they scream and symbolically raise their carved poles in the air in honour of their region. Ten mysterious boxes stand in the centre of the circle.

The scouts have been collecting pasta, rice and tinned foods for weeks to hand them out to the owners of soup kitchens in Athenian suburbs – such as Tavros in the south west of the town – together with Boroume. Stella and her son Zacharias walk up to them without a word and place three plastic bags next to the boxes. They saw the Boroume initiative on facebook and spontaneously decided to join it. Otherwise Stella would have had to throw the food away: she lives and works in a hotel in Crete in the summer. ‘I’m here to help those who need it, even if I have my own problems,’ she explains and links arms with Zacharias before heading home again. The food is stowed away in vans, the scouts have already moved along. Daily life in Athens – devoid of any state of emergency.

This article is part of a series of special monthly city editions on ‘EUtopia on the ground’; watch this space for upcoming reports ‘dreaming of a better Europe’ from Warsaw, Naples, Dublin, Zagreb and Helsinki. This project is funded with support from the European commission via the French ministry of foreign affairs, the Hippocrène foundation and the Charles Léopold Mayer foundation for the progress of humankind.

This article is part of a series of special monthly city editions on ‘EUtopia on the ground’; watch this space for upcoming reports ‘dreaming of a better Europe’ from Warsaw, Naples, Dublin, Zagreb and Helsinki. This project is funded with support from the European commission via the French ministry of foreign affairs, the Hippocrène foundation and the Charles Léopold Mayer foundation for the progress of humankind.

Translated from Armut: Auf der Suche nach dem Ausnahmezustand in Athen