Polish migrants post-crisis in Ireland: is there no place like home?

Published on

EU enlargement in 2004 meant that the Poles made the most indelible imprint on Irish society - and surprise, they're happy in their new home, despite the fact that both countries have experienced polar fortunes in the recent recession

In late 2009, as most of the world continued to sludge through the dregs of an economic recession that had spared few, Poland became the only country in the eurozone to register economic growth at a stable rate of 1.2%. Long a country associated with a dark, depressing climate and eccentric politicians and customs, since its accession to the European Union in 2004, the country is fast remodelling itself as a success story - with a capable, educated workforce, attractive cities steeped in decadent architecture and a foreign policy that has successfully carved out a functional, proactive role for Poland in the world.

2000 kilometres to the west, the picture was looking rather different. With experts predicting that the Irish economy would decline by a further 7% before the country could celebrate christmas, the population were already struggling through the gloomiest recession in their history. Constructions sites around the country lay half built and eerily empty. Social welfare offices filled up with qualified lawyers, accountants, architects and young graduates. Bankers resigned and politicians scurried to pull together the remains of a Celtic Tiger economy that had been reduced to a hungry stray kitten. The good days were over.

Happy in Ireland

The economic darling of the EU, a visit to Ireland in the ten years between 1995 and 2005 showed off a gleaming population, high on their own success, downing everything from over-priced cappuccinos to over-priced homes. When EU enlargement opened up new borders and new possibilities for the countries of central and eastern Europe, it was the Polish who made the most indelible imprint on Irish society, with Polish shops, newspapers and adverts popping up in a population that up to that point had itself been used to creating immigrant communities abroad. By 2005, it was estimated there were 200, 000 Poles living in the country.

'I've never had any negativity towards my working here since the economic downturn'

Between April 2008 and April 2009, only 30, 000 central and eastern European migrants chose to return, the majority choosing to rebuff the growing success of their own country and ride out the economic storm in their newly settled home. 'The work ethic is totally different in Poland,' explains Dawid Kuc, from the stately town Nowy Sącz in southern Poland, who moved here in September 2007. 'My friends who work in the same field as me in Poland work really late evening and weekends. The quality of life here is better.' A masters graduate in financial management, Dawid was looking 'for something different' upon graduation and found it in the Dublin offices of KPMG. 'I have never had any negativity towards my working here since the economic downturn,' he says. 'Work wise, there are the usual things that everyone faces, some salary cuts, perhaps some promotion opportunities that won't happen now, but overall I really like my life and my job here in Ireland. There is a great Polish community here and life is good.' Dawid does not plan on returning to Poland in the near future. Justyna Taraga, from Poland's fourth largest city Wroclaw, has been living here since 2004. Working in banking customer care, she is equally upbeat. 'Of course lots of my friends lost their jobs, both Polish and Irish,' she admits, 'but many are on social welfare now, or doing courses to improve their skills. For me, I have a fun job, I have met loads of people....I am happy here.' Justyna has no immediate plans to move home.

Not just here to make money

There is hope that the vibrancy and positivity of the Polish community in Ireland could bring energy and vigour to the depressed Irish psyche, left wounded from the recent bust. While there had been much talk in the country during the boom years of the positive effects of the Polish gene pool in increasing the attractiveness of the somewhat pasty Irish, it now may be that their upbeat attitude in the face of difficulty might just help matters too. 'My Polish girlfriend is great at putting things into perspective,' says Dylan Francis, a pub worker from Galway. 'She couldn't get over the recent furore over the 2inch snowfall in across the country and how most of us were moaning about the freezing weather. It was minus two here. In Poland, they are used to minus 20.'

There is hope that the vibrancy and positivity of the Polish community in Ireland could bring energy and vigour to the depressed Irish psyche, left wounded from the recent bust. While there had been much talk in the country during the boom years of the positive effects of the Polish gene pool in increasing the attractiveness of the somewhat pasty Irish, it now may be that their upbeat attitude in the face of difficulty might just help matters too. 'My Polish girlfriend is great at putting things into perspective,' says Dylan Francis, a pub worker from Galway. 'She couldn't get over the recent furore over the 2inch snowfall in across the country and how most of us were moaning about the freezing weather. It was minus two here. In Poland, they are used to minus 20.'

Where issues of integration continue to be a topic of concern with regard to Ireland's new found cosmopolitanism, many Irish people are glad of the solidarity of the Polish in recent months. 'There was a lot of talk in the good days that the Poles were just here to make money, send most of it back home and then leave when the going got tough,' says taxi driver Derek O'Hana. 'To be honest, it's nice to see that many of them have roots down here and are sticking out the tough times with us. They are good workers, and we need them in crisis as in the good times.' Justyna sums up the sentiment. 'If you have been here for many years it's not so easy just to up and leave because the economic situation has changed. Most of us have partners, cars and apartments by now. Our lives are here.'

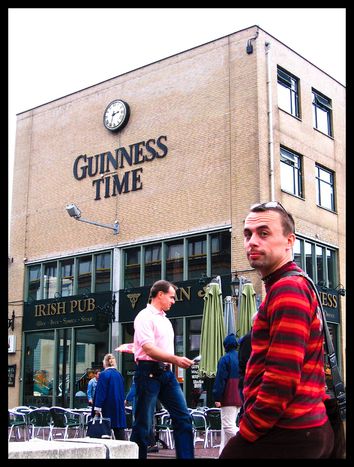

(Images: main by ©przemion ; Polish girl working in a cyber cafe in Ireland by ©Julie70/ Flickr)