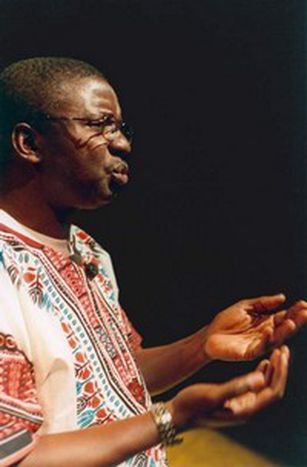

Pie Tshibanda: ‘crazy black man in a white man’s country’

Published on

Translation by:

veronica newington

veronica newington

The Congolese writer and storyteller, 55, in exile in Belgium, feels that Europeans 'don’t want to take a long hard look at themselves'

'10 o’clock, Saturday, my place.' This is Pie Tshibanda’s answer when invite myself over for a café bruxellois. Tangissart is a small village about 30km from Brussels. The jack-of-all-trades entertainer mentions his six children often in his shows. Today, one of them opens the door for me, another gives me a smile, and a third wanders in to in the kitchen as we talk, looking for a bite to eat.

Champion for those without a voice

Tshibanda is a psychologist, writer and story-teller, who draws his inspiration from his country’s history. 'Some people who read my work in the Congo sometimes complain, saying you always write about sad things!. I usually answer, I’m sorry, but it’s the life that I have led!.'

After receiving his psychology licence from Kisangani University at the end of the seventies, Tshibanda quickly got into teaching, whilst continuing to write. As my subject immerses himself in talk about his early writing I see a story-teller in a theatre, transposed into the dining room where the sizzling of rice mixes with the bitter-sweet smell of spices. Tshibanda may not be sporting his customary multi-coloured African shirt, but he does have the same smile, body language and mischievous look.

So what were his first books about? 'This will make you laugh,' he winks. 'The disappointments of my love life.' Tshibanda did not wait long though to tackle more serious topics, such as prostitution and rogue witchcraft, that affected the Congolese people at the time though. 'I avenge the suffering of all those who suffered. I fulfil my mission as a writer, he who speaks in the name of those who cannot speak.'

The story that Tshibanda tells during his shows A Crazy Black Man in the White Man’s Country and I Am Not A Witchdoctor start at the beginning of the nineties. 'At the time, things were changing. Mobutu (dictator president 1965 - his death in 1997), was close to relinquishing power. He wanted his chief opponent in the Congo, Étienne Tshisekedi (former prime minister of Zaire, or the current Democratic Republic of Congo, and an ethnic ‘Luba’ from the Kasaï region), dead. To weaken Tshisekedi, Mobutu decided to take against the Kasaïan community. Many of them, who lived in the Katanga province and worked in the mines there, were to perish during the ethnic cleansing ordered by Mobutu.

Tshibanda, who himself originally is from Kasaï, criticised the massacres through a cartoon and a video film. 'From that moment on, everything changed radically. I was no longer an ordinary refugee, but a bothersome witness who left a trail of evidence. I had to leave overnight.'

Suitcased arrival

Onstage, he relives his arrival in Belgium with a great deal of humour. Yet the smile I see on his face as he recounts an ironic anecdote is a fleeting one. 'I came from the Congo with a suitcase. I wasn’t one of those who came empty-handed to look for help and to steal everything.' His works mix humour and death, because 'humour’s purpose is to sweeten the bitter pill.'

Shortly before his exile, Tshibanda worked as a business psychologist at Lubumbashi, Congo's second largest city. Upon his arrival in Belgium in 1995, he enrolled at the University of Louvain-la-Neuve and took other courses. The early years were to be lonely ones: a thousand administrative hurdles prevented his wife and their six children from joining him in Belgium.

Another version of history

The dining room's yellow and purple walls are bathed in the weak spring sunshine. I find myself thinking about the house that Tshibanda built in Lubumbashi, now transformed into a health centre. Woth it, he records how he has 'found respect, paradoxically more than in my own country.' After a silence, Tshibasha suddenly points his finger at me. 'I have received two medals of honour here. Each time it made me feel like crying, saying, I had to come to Belgium to receive a medal. Nobody is a prophet in his own land.'

Back onstage, Tshibanda doesn’t hesitate to remind the audience of the Belgian Crown’s colonial past. 'That was what returned Congo to Belgium. People should know that during colonisation those who didn’t produce enough had a hand cut off. I think that Europeans don’t want to take a long hard look at themselves.'

Forty-six years after the Congo became independent, Joseph Kabila became the first democratically elected president in 2006, according to the international press. But for Tshibanda, 'history simply repeats itself.' The noise of the television and the raised voices of his two youngest children bring me back from Kinshasa to Tangissart.

When I ask him about the European Union’s role in the DRC’s political future, his response is pithy. 'The EU is going to play a significant part in the building of what it calls democracy, and what threatens to create another dictatorship.' His assessment of Europe is critical, but not devoid of hope. 'I would like this Europe to be not simply an economic Europe, but also a social Europe, with a human dimension. If this enlargement can bring some balance to the world, that could be a wonderful thing.'

Translated from Pie Tshibanda : « les Européens n'ont pas envie de se regarder en face »