Pegida: Why Dresden? (Part Two)

Published on

Translation by:

Kath Burns

Kath Burns

Pegida has gripped Dresden, the capital of Saxony. But what more should we know about the city's social and political culture?

In the shadows

A gulf has now emerged between local people and "big politics". In Germany's regional media, there hasn't yet been an open and contentious discussion about German or global politics. Debates are limited by the near total split in public opinion, but that split is barely noticed by many. Hardly anyone in Berlin reads east Germany's regional newspapers, and regional correspondents in east Germany working for national papers haven't held a prominent status in the past.

Despite that, the current conflict isn't the first to highlight just how deep the gulf is. It started after the 9/11 attacks. While Saxony officially adhered to the national line of "limitless solidarity", some local teachers were reprimanded after it was reported that they had expressed a different stance in their classrooms. It was therefore impossible for someone to openly express their disagreement or hold opposing political views, which are some of the basic principles of a democratic society.

The problem of indifference

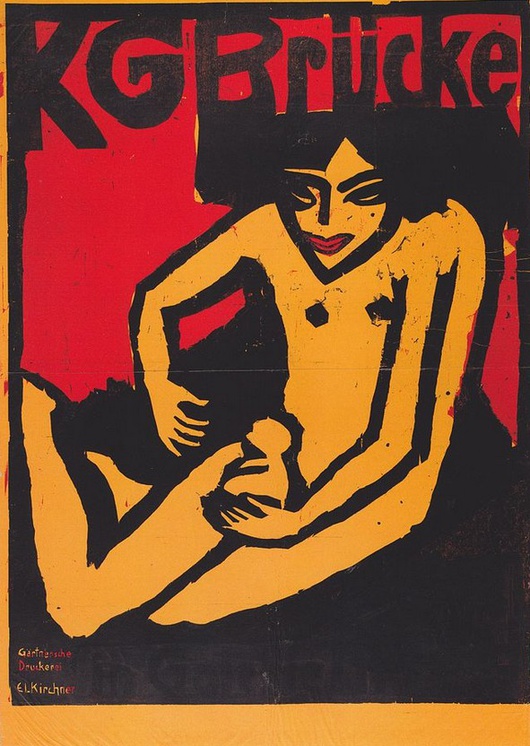

An old German proverb about Saxony's three regions says that people produce in Chemnitz, they trade in Leipzig and they consume in Dresden. As a former royal residence and home to a large military base, Dresden has historically had a special relationship with the government and authority, with all good things being seen to come from the prince and the state. As a result, reserved or critical attitudes towards the authorities have generally played second fiddle. Although critical or innovative thinkers have gathered in Dresden in the past, the widespread indifference of urban society has prevented them from thriving. The best known example is probably a group of expressionist artists known as Die Brücke ("The Bridge"), which quickly left Dresden due to the lack of response or support they faced. The young artists were architecture students at the city's technical university, and they found that neither the city itself nor the university kept this wonderful heritage of creativity and innovation alive.

An old German proverb about Saxony's three regions says that people produce in Chemnitz, they trade in Leipzig and they consume in Dresden. As a former royal residence and home to a large military base, Dresden has historically had a special relationship with the government and authority, with all good things being seen to come from the prince and the state. As a result, reserved or critical attitudes towards the authorities have generally played second fiddle. Although critical or innovative thinkers have gathered in Dresden in the past, the widespread indifference of urban society has prevented them from thriving. The best known example is probably a group of expressionist artists known as Die Brücke ("The Bridge"), which quickly left Dresden due to the lack of response or support they faced. The young artists were architecture students at the city's technical university, and they found that neither the city itself nor the university kept this wonderful heritage of creativity and innovation alive.

Observers have long been fascinated by the fact that Dresden's voter turnout is consistently 10% higher than Leipzig's. It's particularly surprising given the fact that citizens take to the streets much more frequently in Leipzig, as they did in 1989 and in the resistance against neo-nazi protests. As a local motto states, Leipzig is known for holding its ground, so neo-nazis migrated towards Dresden, where they were free to march in the streets for far too long without being bothered by the city's inhabitants. Dresden is undoubtedly one of the most prominent east German cities in terms of business, science, culture and tourism. It also has the country's high birth rate. But sadly that positive development hasn't permeated the whole city or region.

Saxony deliberately focused on the idea of Dresden as one of Germany's most prominent cities after the fall of the Berlin Wall. As a result, Dresden saw a boom in various sectors. But as the city's population grew rapidly, its outskirts were becoming less and less inhabited, with fewer city dwellers moving out into the country. In the city, rent prices – which, up until that point, had been affordable – suddenly rocketed, and schools and nurseries popped up left, right and centre. Meanwhile, out in the countryside, schools were being forced to close one after another and the housing market collapsed. Despite the perceived success of Dresden's social and economic development, some areas found themselves left by the wayside.

Dresden as a victim

Many of Pegida's members are, or are close to, fans of football club SG Dynamo Dresden, where a xenophobic and violent crowd can still be found. Whenever the club is fined for its violent fans' behaviour, the fans themselves hand over the money, while the German Football Association "mafia" consistently claim that Dresden is a victim of the press.

Many were happy when UNESCO named Dresden's Elbe Valley a world heritage site in 2004. However, it was widely forgotten that the award brings certain responsibilities with it. The World Heritage Committee's decision to revoke the title just five years later because of the construction of Waldschlösschen bridge was badly taken and widely criticised. Although Germany's Federal Constitutional Court decided not to take legal action to demand that work on the bridge cease, their decision highlighted that possible outcome. Yet again, dark forces seemed to conspire against Dresden.

Many were happy when UNESCO named Dresden's Elbe Valley a world heritage site in 2004. However, it was widely forgotten that the award brings certain responsibilities with it. The World Heritage Committee's decision to revoke the title just five years later because of the construction of Waldschlösschen bridge was badly taken and widely criticised. Although Germany's Federal Constitutional Court decided not to take legal action to demand that work on the bridge cease, their decision highlighted that possible outcome. Yet again, dark forces seemed to conspire against Dresden.

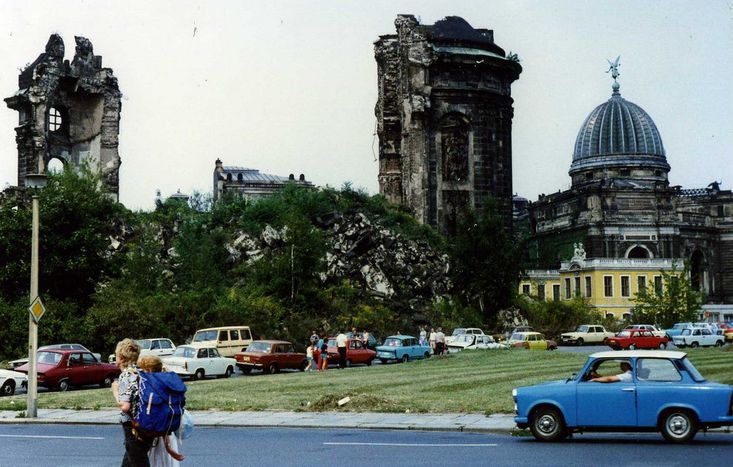

The myth of Dresden being a victim dates back to February 13th 1945. The memory of Dresden's bombing on that day was twisted first by the Nazis and then by the communist SED party. Their shameless exaggeration of the number of victims through propaganda elevated Dresden's status as a victim above and beyond the destruction in other European cities, many of which were worse hit by both German and allied bombs. Neo-nazis throughout Europe have exploited the myth of Dresden as a victim for their own ends, and the city's own people and politicians have had difficulty in opposing that exploitation for far too long. Emphasising Dresden's victim status through propaganda has been a way to avoid confronting the city's National-Socialist and communist history. Turning a blind eye rather than facing up to both past and present captures the victim mindset — it's always someone else's fault; there are always bad guys to blame. With fair criticism being voiced throughout Germany about Dresden's ambivalence, at best, many now feel that their status as victims has once again been reaffirmed. It's a vicious circle which must be broken at all costs.

This article by Dietrich Herrmann and Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung has been reprinted thanks to a Creative Commons licence.

Part One of this series of articles on Pegida is available here, and Part 3 will be published soon.

Translated from Pegida: Warum gerade Dresden? (Teil 2)