Party burnout in Paris, so go to Berlin

Published on

Translation by:

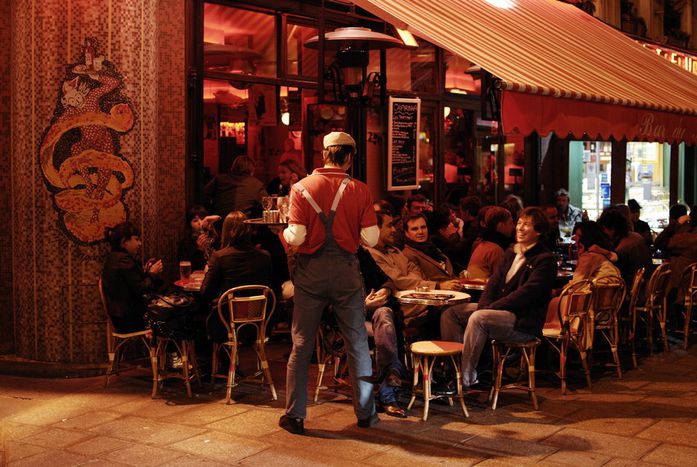

Ellie Banks'Sssssh, go in quickly,' whispers the bouncer of the electro bar 4Elements on the Place de la Republique. The lights are out in the flat above. It is 11pm, a Saturday evening in Paris. The one-time nightlife mecca of Europe is turning into a sleepy little town, a trend that threatens to continue

Paris is burning all night long sang New Zealand musician Ladyhawke only last summer, but those acquainted with Manu Chao's former band, the Spanish-French-Portuguese Mano Negra, knew the real truth about Parisian nightlife in 2002: Tout est si calme qu’ca sent l’pourri, Paris va crever d’ennui! ('Everything is so still, it’s rotting away, Paris is dying from ennui!')

If you listen to Eric Labbé, electro-musician who spins at the Parisian record shop My Elektro Kitchen, the French capital's nightlife is dying in the truest sense of the word - just slipping away. The town itself has come to rest in recent months, since more clubs, like the legendary but bankrupt La Loco in the Pigalle quarter, have been closed down. Concerts and festivals are becoming equally rare, not counting the mainstream international artists, who still manage to fill big concert halls like the Zenith on the northern outskirts of the city. A cultural tragedy in the birthplace of the annual open-air street party La Fête de la Musique. The last lights go out!

Still, the local lovers of night-time entertainment aren’t taking this lying down. Together with other artists, Eric Labbé has brought the Quand la ville meurt en silence ('When the town dies in silence') campaign to life. In less than a month, almost 13, 000 signed a petition to numerous politicians, hoping to save the city's nightlife and culture from ruin. In the petition, they emphasise the economic and cultural significance of nightly entertainment for the whole region, and demand immediate political intervention, a reduction in administrative obstacles and more premises to become available for cultural events.

In truth, the noise prevention laws, the horrendous rents in attractive locations and not least the smoking ban brought in in 2008 have really dampened the party spirit here. Essentially, any and every irritated Parisian can call the police to complain about the volume in the bar next door. According to decree 98-1143 of 15 December 1998, the legal decibel limit is 105 dB. Every venue must also be able to produce a study into the consequences of noise pollution in the area, or the party is over. This must be at least partially responsible for the number of lights going out in the 'city of lights'.

Berlin calling

Residents may well be pleased with their reclaimed peace and quiet, but the rejected party people are just moving on to pastures new. Today's hottest musicians play in New York, Tokyo or Berlin. Paris-based German minimal DJ Phil Stumpf has already complained in a cafebabel interivew about his difficulties with the local clubbing scene and the lack of underground culture. Maybe the mayor of Paris, Bertrand Delanoë, should ask his German counterpart Klaus Wowereit how Berlin has come to be seen as a mecca for club-goers for some time now. 'Wowi' would probably mention the cheap rents, the countless bars open all night - would take him into Berghain/ Panoramabar, currently the 'best techno-club in the world' which lies between Kreuzberg and Friedrichshain, if you believe the electro magazine DJMag. Delanoë, on the other hand, could only complain about the closing of The Deep in the Marais district, and the end of hot nights in Les Bains Douches ('The Bath Houses') just around the corner, two clubs that have long been popular in Paris' gay scene.

While young fun-seekers from around the world dance the night away in cheaply rented factory-floors by the Spree, they can only squeeze into tiny bars along the Seine, or visit one of the few overly-expensive clubs, like the famous Rex club on the Grands Boulevards. There, you will pay up to 20 euros (£18) entry - and if the music isn’t so great, you can’t even reasonably numb yourself , as each beer will cost you a shameless 6 euros (£5.45). The only glimmer of hope is the long awaited re-opening of the indie dive Fleche d’Or ('The Golden Arrow') in the 20th arrondissement (eastern Parisian district), which had been closed for months and had gradually fallen into ruin. But it’s still impossible to say whether the future of this arrow really will be so golden.

While young fun-seekers from around the world dance the night away in cheaply rented factory-floors by the Spree, they can only squeeze into tiny bars along the Seine, or visit one of the few overly-expensive clubs, like the famous Rex club on the Grands Boulevards. There, you will pay up to 20 euros (£18) entry - and if the music isn’t so great, you can’t even reasonably numb yourself , as each beer will cost you a shameless 6 euros (£5.45). The only glimmer of hope is the long awaited re-opening of the indie dive Fleche d’Or ('The Golden Arrow') in the 20th arrondissement (eastern Parisian district), which had been closed for months and had gradually fallen into ruin. But it’s still impossible to say whether the future of this arrow really will be so golden.

Clubbing in the suburbs

Nevertheless, it would be too easy to put the blame for this decline on mean real estate sharks and money-grabbing club owners. The readiness of Parisians to search out a new underground scene has its limits – in particular one very obvious limit: the Boulevard Peripherique (ringroad) is not just the town border. The terrain of most nightowls ends this side of the city tram lines. And yet, old industrial grounds and open spaces could be really fertile soil for the urban lifestyle. We can‘t forget that the suburbs were the birthplace of the Tecktonik phenomenon, the dance-music-fashion movement that spread out from the Parisian suburb into international centres in 2000. Rather than heading to Tokyo or New York, anyone up for a dance could take a night bus right to the centre of the action, and there they could could cry Paaartyyyy as loud as they like!

Translated from Paris: Party-Burnout an der Seine