Paris suburbs: cliche piled upon cliche

Published on

Translation by:

James FrisciaIt's a common European stereotype to define the French suburbs by their one-time violent rioting. But those events took place five years ago. On a visit to the 'banlieue' of Paris today we meet three residents who tell their story - a father-of-three, a social worker and a budding regional election hopeful

This is the story of a man who falls from a fifty-story building. As he falls, he tries to reassure himself by repeating: ‘So far, so good. So far, so good.’ But it’s not the fall that matters. It’s the landing.

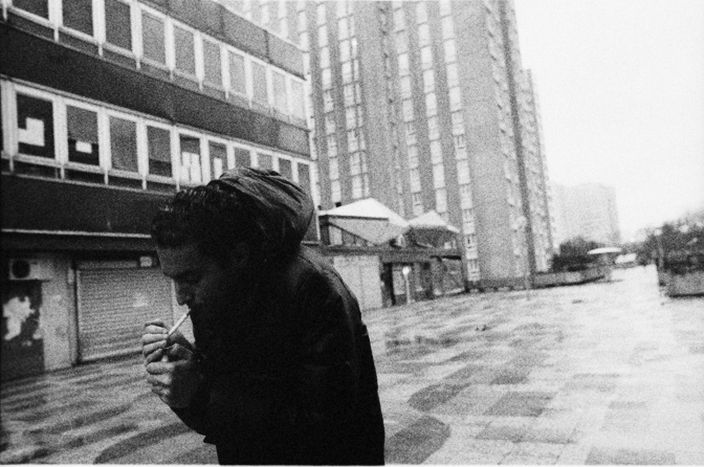

This quote, set over black and white images of youths clashing with police in one of the many outlying neighbourhoods of Paris, starts the film The Hate ('La Haine', 1995), from Parisian director Mathieu Kassovitz. In many ways the film was a landmark in exposing the reality of the ‘banlieue’. In 2005, one suburb burned with flames that lit the fuse of political discussion. The reality of the situation was finally shown on television as violence erupted. Problems only make the news when they surface, not while they are brewing. The Hate premiered in 1995 and should have set off alarm bells. Apparently they were ignored.

‘Banlieue’ means suburb, any neighbourhood located on the outskirts of a town or city, whether of a depressed area or a middle or upper class residential district. However, recent circumstances have given it connotations of a slum - architecturally isolated, inhabited primarily by immigrants and beset with crime. Glossing over realities would reassure the average conservative citizen, but it would mean obscuring the truth. The Parisian banlieue is extremely complex, a real place inhabited by people of flesh and bone, with problems but also with solutions. This is an attempt to understand its past, present and future through the stories of three people.

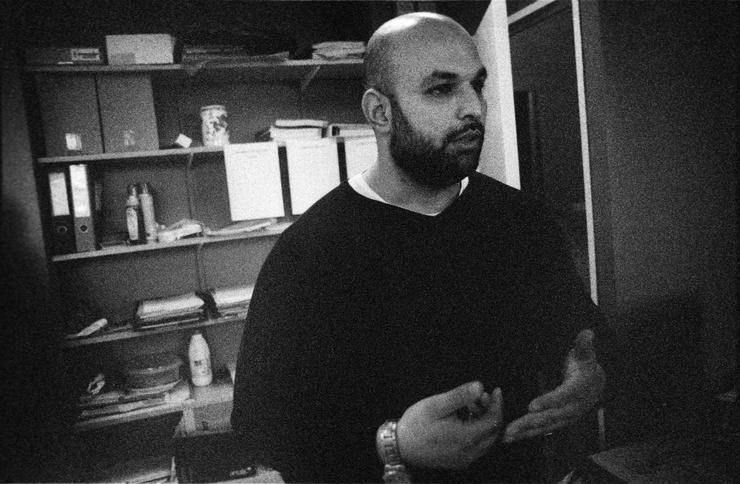

Nabil Boub, social worker, Saint Denis

Saint Denis is perhaps the most well-known banlieue. Situated in the north, it is a vibrant and pleasant city, however not without its issues. It is far from the city centre geographically, but socially too. City planning in the French capital filters and distributes its citizens into districts: if you travel up to Saint Denis on public transport, you would notice how the skin of the travellers gradually becomes the darker colours of the French colonies. Although the riots of 2005 did not occur here (they were more to the north, in communes like Montfermeil and Clichy-Sous-Bois), Saint Denis has areas that undeniably resemble The Hate.

'If you travel up to Saint Denis on public transport, you notice how the skin of the travellers gradually becomes the darker colours of the French colonies'

Sussaie Floréal Courtille, located at the bottom of a large block of flats, is one of the thirteen youth social centres in the city. Established in 1998 to help stabilise the social life of the neighbourhood, it also aims to engage young people in politics and encourage them to exercise their right to vote. Nabil Boub is one of its social workers. He agrees to speak, but prefers not to be photographed: 'Essentially it was this very same media that escalated the violence,' he explains. 'Biased and manipulated images led to competitive violence among the youth.' Nabil wishes that reporters would cover everyday events in the neighbourhood, and not just the problems. Finally he allows us to photograph him; he only wanted to avoid being manipulated or used. The people of Saint Denis do not want you to inquire into the riots nor their connection to them.

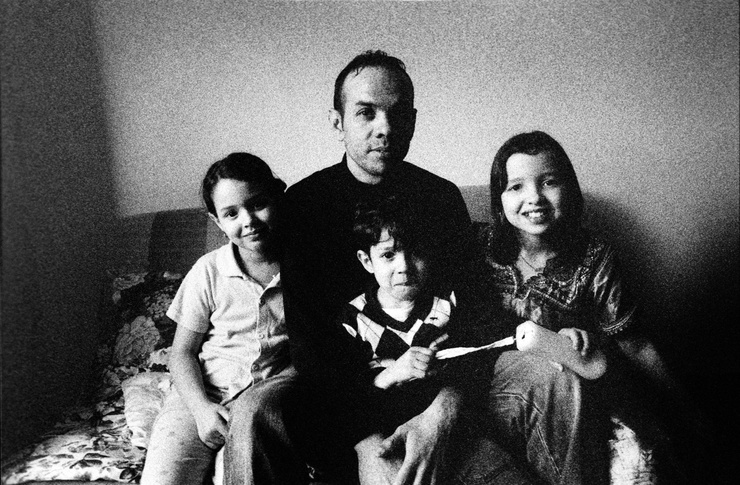

Benalí Khedim, worker, parent and social housing resident

Benalí, 33, is of Algerian descent. He lives with his wife and three children in a social housing unit measuring 25 square meters in Saint Denis. He has been in France eight years, earning a good living in construction. Earlier, he had lived as an illegal immigrant in Spain, Denmark and Finland. Benalí does not feel like a French citizen with full rights: for eight years he has been required to live in social hotels rented by the municipality. He cannot obtain his own housing. 'You need to show a salary at least three times greater than the rent you would pay as well as have a security deposit.' And he doesn’t have that kind of money.

Previously Benalí lived in the centre of Paris. In fact, officially he continues living there, where he works and his children go to school. 'I feel isolated in a way, like a tennis ball hit from one side to another. I was thrown out of the city centre, but I still work there. The administration promised me housing in Paris, but that promise remains unfulfilled. Meanwhile, the municipality of Saint Denis does not recognise me as a citizen of its city.' In France, there is a double standard: immigrant workers and undocumented aliens need to pay taxes, but they don’t enjoy the same rights as those of French citizens recognised by the state.

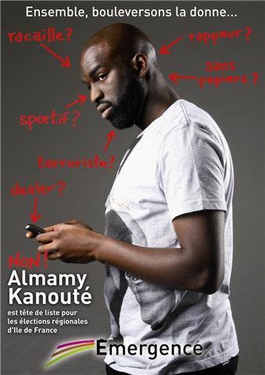

Almamy Kaonuté, leader of civil political movement Emergence

If we followed clichés on how he looks, we might think him a football player without the legal documents, a drug dealer or a hip-hop artist. However, 30 year-old Almamy Kaonuté from the civil political organisation Emergence is a frontrunner in the March regional elections. He is a person of clear ideas and direct discourse. He meets us in the prosperous locale of Saint-Maur-des-Fossés, where the group prepares for the regional elections of 14 March. 'This association was created in 2008 following the municipal elections. We realised that we were not represented by the local politicians. We decided to organise ourselves around the notion of concord among Parisian suburban communities.' The leader of Emergence works as a social educator. As his family is from Mali, Almamy truly knows what he is talking about: 'In this society, a serious hypocrisy prevails. I am French because I was born here, but my parents are not. I have never read the story of the ex-colonies in textbooks nor have I ever heard mention of the true diversity in French society. I have never felt I fit the accepted image of France.' For Almamy, problems in the suburbs result from a combination of reasons: a failed urban model, unemployment, discrimination and social segregation based on skin colour… 'We are tired of promises from professional politicians. We don’t need to be elite to know about the issues in our own neighbourhoods. The divide between the political class and the people is continually greater and, if we don’t do something, the problems will worsen. For this reason we want to inspire young people to vote at the polls instead of burning them.' Almamy knows that it’s not the fall that matters, but the landing.

If we followed clichés on how he looks, we might think him a football player without the legal documents, a drug dealer or a hip-hop artist. However, 30 year-old Almamy Kaonuté from the civil political organisation Emergence is a frontrunner in the March regional elections. He is a person of clear ideas and direct discourse. He meets us in the prosperous locale of Saint-Maur-des-Fossés, where the group prepares for the regional elections of 14 March. 'This association was created in 2008 following the municipal elections. We realised that we were not represented by the local politicians. We decided to organise ourselves around the notion of concord among Parisian suburban communities.' The leader of Emergence works as a social educator. As his family is from Mali, Almamy truly knows what he is talking about: 'In this society, a serious hypocrisy prevails. I am French because I was born here, but my parents are not. I have never read the story of the ex-colonies in textbooks nor have I ever heard mention of the true diversity in French society. I have never felt I fit the accepted image of France.' For Almamy, problems in the suburbs result from a combination of reasons: a failed urban model, unemployment, discrimination and social segregation based on skin colour… 'We are tired of promises from professional politicians. We don’t need to be elite to know about the issues in our own neighbourhoods. The divide between the political class and the people is continually greater and, if we don’t do something, the problems will worsen. For this reason we want to inspire young people to vote at the polls instead of burning them.' Almamy knows that it’s not the fall that matters, but the landing.

Images: ©Simon Chang; Emergence poster

Translated from Una mirada a la 'banlieue' de París