Painting Congolese history: Tshibumba Kanda Matulu

Published on

Amid the clichés of contemporary media coverage, the paintings of Tshibumba Kanda Matulu offer an unparalleled opportunity to understand the hopes and fears underlying the history of the Congo

When we think of the Congo, it is hard to see past the daily stream of images of war and poverty that are thrust on us by the media. To understand something of the country’s tumultuous past, paintings can tell you as much as a thousand photographs. Few painters could teach you more than Tshibumba Kanda Matulu.

In his most famous work, the History of Zaïre (1973-1974), Tshibumba combined elements of traditional African storytelling with a contemporary style of urban popular art to create his own vision of Congo’s past. This vision, while personal, articulated a system of shared memory that gives an unparalleled insight into Congolese history.

Johannes Fabian

For many years Tshibumba worked as a painter in Lumbumbashi, selling small figurative scenes to local customers. But he felt confined by the artistic canon dominant in his day. He thought of himself as a historian and an educator of his people, but he knew that his local clientele would never offer him an opportunity to express his visions of national unity in paintings.

It was through the person of Johannes Fabian, a German anthropologist who worked and lived in Lumbumbashi, that Tshibumba found the sponsorship he needed.

Fabian met Tshibumba in 1973 and quickly recognised his knowledge of history and his talent for storytelling. The two men developed a close friendship and in the following year Tshibumba revealed his idea: to paint the entire history of his country in a series of paintings. The collaboration between them resulted in Fabian’s book Remembering the Present – Paintings and popular history in Zaïre.

Popular history

To appreciate and learn from the work of Tshibumba one must understand that his History is a popular history. This means that his work is not an exact or factual account of what happened. Rather, while it is in line with shared popular understandings, on many occasions it doesn't follow the actual historic timeline. Tshibumba did not always have the resources to check the accuracy of his work. But sometimes his mistakes are intentional and his exaggerations are used ironically to stimulate discussion. Fabian explains in his book: 'His errors were meant to shock and amuse'.

A felt history

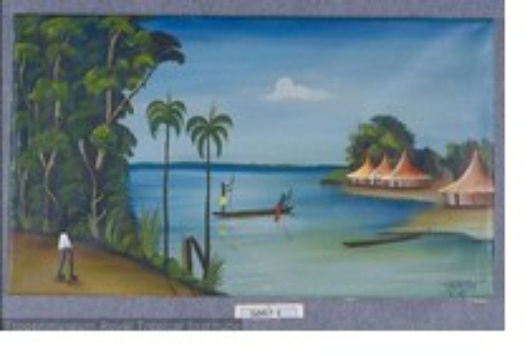

The History of Zaïre begins with the pre-colonial period of the Congo. This stage is illustrated by depictions of ‘village life’, ‘when people knew how to live’. Tshibumba’s comments testify to a respect and nostalgia for the traditional life of another era. In his paintings he returns to a mythical landscape, to a conception of Africa before colonialism.

His next paintings are of the European explorers who visited the Congo. Starting with the Portuguese who entered the Congo in 1487, Tshibumba also presents the famous explorers Livingstone and Stanley, with whom the European fascination with the Congo started. From Tshibumba’s paintings it becomes clear that for the Congolese they were the pioneers of an intensifying European interference.

His next paintings are of the European explorers who visited the Congo. Starting with the Portuguese who entered the Congo in 1487, Tshibumba also presents the famous explorers Livingstone and Stanley, with whom the European fascination with the Congo started. From Tshibumba’s paintings it becomes clear that for the Congolese they were the pioneers of an intensifying European interference.

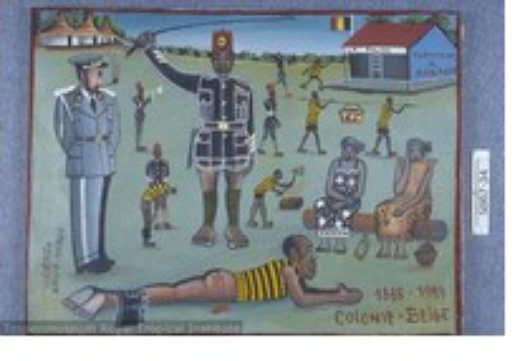

The Belgian King Leopold II, who reigned at the beginning of the colonisation of the Congo, is portrayed several times. Most important for Tshibumba are the incidents that occurred in the Congo during the period of the Congo Free State, when the country was actually Leopold’s private property. The stories of this period keep alive the memories of Belgian oppression.

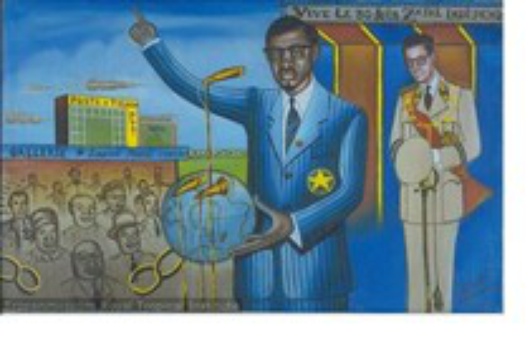

In the second half of the 1950’s the cry for independence becomes louder. One of the leaders of the struggle was Patrice Lumumba, a dedicated pan-Africanist whose rise and fall is represented in a series of eighteen paintings.

In the second half of the 1950’s the cry for independence becomes louder. One of the leaders of the struggle was Patrice Lumumba, a dedicated pan-Africanist whose rise and fall is represented in a series of eighteen paintings.

Independence was celebrated on 30 June 1960, and Lumumba delivered a famous speech in which he condemned the colonial period. Despite becoming prime minister, the government of Lumumba lasted just ten weeks, as first the province of Katanga declared its independence with Belgian support, and then a coup led by the army leader Colonel Joseph Mobutu led to Lumumba’s arrest. On the 17 January 1961, Lumumba was killed in mysterious circumstances.

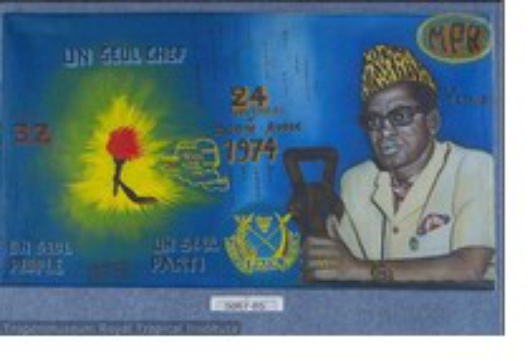

The paintings depicting the years following independence show the hardship and pain of the Congolese people during this period. Joseph Mobutu assumes power in 1965, and proceeded to rule with an iron fist, suppressing the political opposition. He instituted new intuitions of national identity, and changed the name of the country to Zaïre in 1971. During his rule foreign-owned companies were nationalised and an enormous cult of personality was created around Mobutu.

The paintings depicting the years following independence show the hardship and pain of the Congolese people during this period. Joseph Mobutu assumes power in 1965, and proceeded to rule with an iron fist, suppressing the political opposition. He instituted new intuitions of national identity, and changed the name of the country to Zaïre in 1971. During his rule foreign-owned companies were nationalised and an enormous cult of personality was created around Mobutu.

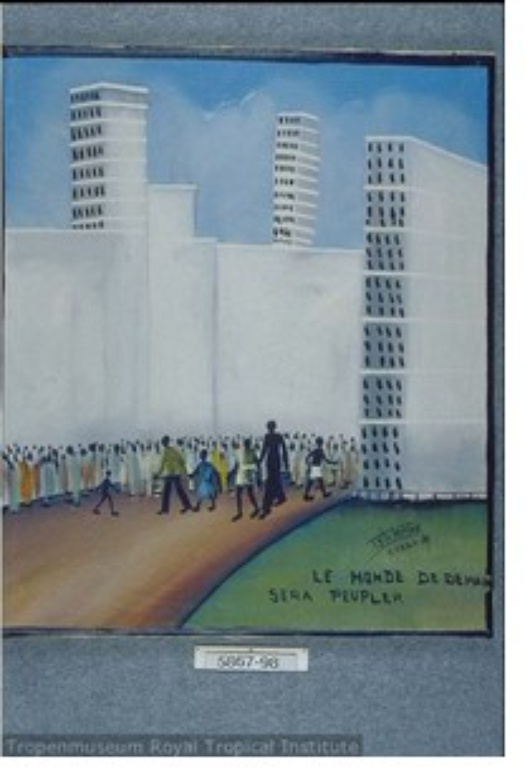

The History of Zaire ends with paintings depicting events that took place in the early 1970’s. But Tshibumba also included paintings in which he gives a possible future for his country. He shows dreams of a new order in which social relations disintegrate and party politics replace religion.

The History of Zaire ends with paintings depicting events that took place in the early 1970’s. But Tshibumba also included paintings in which he gives a possible future for his country. He shows dreams of a new order in which social relations disintegrate and party politics replace religion.

Remembering the present

The History of Zaire looks back to the early 60’s as a time of great hope, with the end of colonialism in sight and a thriving middle class who offered some economic and social stability. Lumumba appears as a messianic figure during the fight for independence. His death foreshadows the horror of what is to come. The most poignant pictures are Tshibumba’s representations of those images which are all too familiar to us today: images of poverty, refugee camps and blue helmeted peace keepers.

Tshibumba's last paintings date from 1981. Various efforts to contact him in the ensuing years have proven fruitless. There is good reason to believe he is dead, a victim of the tragic history of his homeland.