Overworked, underpaid in a French call centre

Published on

Translation by:

Martyn HawkinsToo many young Europeans are forced to work in bad conditions to finance their studies in France. Why a young Italian quit

It’s the end of September 2007 and I’m looking for a job in Paris. I get in touch with a call centre, where some of my friends also work. They interview customers who have bought a car and ask them if they are satisfied. Why not? The whole thing is in Italian so it shouldn’t be a problem. I ring up and they forward me to a girl who speaks Italian with a light French accent. She takes down my name and asks me to send in a CV with a covering letter. The next day I head out to the suburbs. I go past family houses, through narrow streets and then I get to a type of warehouse, which we call ‘Venus’. I come across young people of more or less every nationality. It’s good to see the many different faces and to hear the different accents.

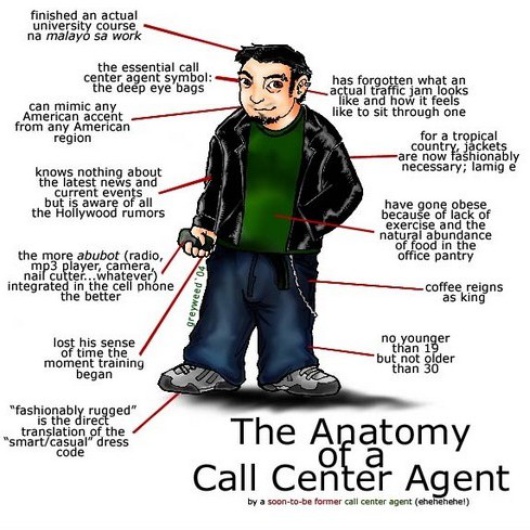

The anatomy of a call-centre-er (Image: nina_theevilone/ Flickr)

The anatomy of a call-centre-er (Image: nina_theevilone/ Flickr)

Poverty of the e(uro)-generation

As I enter, I can already see a queue. I ask around and then notice that people from all over Europe have gathered here. Not just Erasmus students but also ‘normal’ immigrants, who are here looking for work and a better life, and even students from the Sorbonne. They are the other face of the e(uro)-generation. For them, the money has to be enough to cover the rent. They generally get on the web in internet cafés and Saturday is just another working day to them. Incidentally so is Sunday, if their electricity bill is too high again. There are no pictures in the newspapers of this generation, because they don’t exist.

Ciro is 25 and has worked for Venus for a few months. He is an Erasmus student and wants to stay in France to do his masters. As an industrial engineer, he’s interested in logistics and warehousing. I ask him what he gets from the work in the call-centre. ‘It’s ideal for students because you can change your working hours every week. But by working here you can’t learn anything. It’s badly paid too.’ Ciro works up to 25 hours per week according to the demands of the business. However, it’s the relationship with his superiors that he criticises. ‘There is no dialogue. Indeed, you won’t be sacked straight away if you make a mistake, but you won’t have anything explained to you either. The only goal is to do as many interviews as possible.’

Anne comes from Germany, where she studied languages. How long does she wants to stay at Venus? ‘As little time as possible. I need more security.’ Meaning? ‘I don’t want to have to think about money again every week. Sometimes they just change your timetable or sometimes there’s simply nothing to do. Then you only work two days a week and not six. And then how can I pay the rent?’ Anne works on average between 30 and 40 hours and would arather find something in the cultural sector. ‘If you worked here as a full-time-job, you’d go mad.’

Less than 8 euros (£6. 30) per hour

Moving on from under the plastic marquee, we go into the computer laboratory. After the attendance check my new boss explains the working conditions: availability, reliability and a 40 hour probationary period during which we should demonstrate our abilities. There is also a contract for which I learn a new word, vacataire, which in some way describes the type of conditions of this part time position. It means precisely: no holiday entitlement, no sick days, hourly pay, no meal vouchers, and weekly planning. We need not know anything about cars, which we should be talking about. We are just there to write down what the customer at the other end of the line tells us.

We sign to say that we agree not to pass on any of the information we collect during the phone calls to other people, and that we agree that the company can send us home with no pay and no explanation, if on that day there is nothing to do. All that for seven euro 66 cents (£6) net per hour.

A tendon for 10 euros (£8)?

I’m sent into a hall in which the Italian team are sitting. Next to them are the Spanish, German and English teams, as well as the Turkish and Russian groups. And all of them are hanging onto the telephone. I sit myself down next to a young man, who has already worked here for a few months, listen to his questions and read along as he writes down the answers. We have a short break of ten minutes.

I hear how an Italian girl speaks to the French boss. She is 23 and has a torn tendon in her left arm because of holding on to the telephone for too long. The company managed to stop her complaining, on the grounds of third party negligence, by giving her a promotion. Then something catches my attention: There are of course no headsets here either. By the evening, I’ve been on the telephone for eight hours and fifteen minutes, interrupted by a ten minute break every two hours and a 45 minute lunch break which wasn’t paid. At 8am the next morning I’m there again. Around me I can hear people from at least twenty different countries speaking in ten different languages. With a gap of less than half a metre between me and the person next to me, it’s difficult to concentrate on the telephone and write down everything correctly.

The others keep their eyes closed. I feel like a little cog in the wheel, like a worker who has no rights and is replaceable, just like in Liverpool at the start of the industrial revolution. Then something come sto me: I am in Paris, it’s the year 2008 and there are trade unions. They are however, not for us. As I announce that I want to complain because of the working conditions, my supervisor, a south American who keeps his job for 10 euros 20 (£8) per hour, has a simple answer. ‘If it doesn’t suit you, put your phone down and leave.’ And he is right. I put my phone down and go, and it’ll be someone else here at 8am, ringing up these people, only then to hear My husband can’t at the moment, he is in hospital, and then despite this insist on an appointment in two weeks time, in the hope that her husband is back on his feet.

We are in Paris, in the year 2008, and the young people from all over Europe are meeting up in a warehouse. Their only protection is a plastic roof.

For privacy reasons, the names of the people have been changed

Homepage photo: (divine_harvesterTM/ Flickr)

Translated from Call center, un altro modo di dire Europa