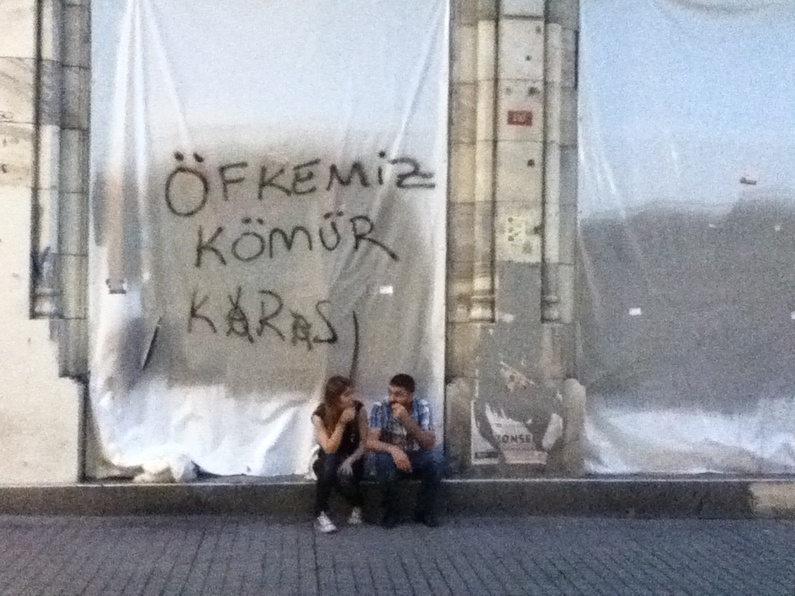

“Our Rage is as Black as Coal”

Published on

Translation by:

Rachel Hutcheson

Rachel Hutcheson

Two weeks before the mining accident in Soma in Turkey, a motion was filed for a safety check and was declined by the ruling party, the AKP. The rage of the demonstrators is now huge. What kind of political consequences does Soma bring with it? The interim conclusion with political scientists and a documentary film maker.

On a Saturday evening in Istanbul, tourists often converse with each other as follows: “Maybe it’s a bit too dangerous, let’s go home instead.” It is a humid Saturday evening in May, Istiklal Street. The street leads from Istanbul’s Taksim Place to the Tünel, the oldest cable car system in Europe. Using this people can enjoy being pulled up from the banks of the River Bosporus, especially on hot days.

Now, however, groups of police have gathered in side streets. The troops wait, smoking and visible or acting bored. Today, unlike on Wednesday when thousands descended on Istikal Street, only a small group has gathered. Then: The first shots, tear gas, screams, hooting. The decision is taken out of the tourists’ hands: they should go home, the Commander shouts.

Now, however, groups of police have gathered in side streets. The troops wait, smoking and visible or acting bored. Today, unlike on Wednesday when thousands descended on Istikal Street, only a small group has gathered. Then: The first shots, tear gas, screams, hooting. The decision is taken out of the tourists’ hands: they should go home, the Commander shouts.

Michalangelo Severgnini (39) watches the scene closely. He looks up from under his red hair and says: “It is my job.” Michelangelo is a musician and documentary filmmaker, comes from Italy and has lived in this city of 14 million people since 2008. His last film, "The Rhythm of Gezi", is about the demonstrations in Istanbul in May and June 2013.handelt von den Demonstrationen im Mai und Juni 2013 in Istanbul.

What Michelangelo knows is that he must be careful when, like today, he goes to protests. It is not known what will happen if the police catch him. He doesn’t want to leave the country. So he tries to stay at the edge of the demonstration, even if there is not much happening today.

It’s bewildering. Many more people were expected after the mining accident in Soma. The previous history is frightening: In 2012 the coal mine in Soma was privatised, and dramatic cost cutting followed. Yet, two weeks before the explosion, the opposition party, the CHP, wanted to know why cuts were being made to the safety of the workers of all things. However, their request was dismissed by Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s ruling party, the AKP.

Simply destiny

Simply destiny

Above all, Erdoğan’s public reaction is shocking: He described the accident as “destiny” which could have happened “anywhere in the world”. At the site of the accident, Yusuk Yerkel, parliamentarian and trusted aide to Erdoğan, kicked a demonstrator. Only after fierce protests did Yerkel resign a few weeks later.

Cansu Ekmekcioglu (27) is appalled at this. She is the president of the Turkish branch of the NGO “JEF”. Furthermore she carries out research at Galatasaray University in Istanbul on social networks and political movements and has many deadlines to meet. She answers questions most throughly by mail, however.

“No-one is backing down, a public apology for Soma has not yet been uttered. I don’t believe that one will come. The costs of political action are simply not paid in this country. The AKP still has its true supporters and Erdoğan is still their beloved leader.” A change of leadership in the predidential elections in August looks unlikely.

Groups of police are everywhere. A sea of uniforms and plexiglass shields. Michelangelo says:

“The most important thing is your face. If you look like a tourist, they will not do anything to you. If you stand there and take photos without a press pass, you’ll suffer the same fate as that guy.” He points to a passerby who is training his smartphone on the police. He is grabbed by the arm and made to produce his ID card.

Before Michelangelo answers the question of whether the Soma protests could present a “new Gezi”, he exhales deeply.

“I wouldn’t say that. Compared to Gezi, which was originally about the cutting down of trees in the parks of Istanbul, Soma is very distant. Of course a few trees are nothing compared to the lives of more than 300 people but it’s more about the symbolism. You take to the streets here, not to protest the incident itself, but instead because you are protesting against something bigger and because your rage is increasing day by day.”

“I wouldn’t say that. Compared to Gezi, which was originally about the cutting down of trees in the parks of Istanbul, Soma is very distant. Of course a few trees are nothing compared to the lives of more than 300 people but it’s more about the symbolism. You take to the streets here, not to protest the incident itself, but instead because you are protesting against something bigger and because your rage is increasing day by day.”

Highly educated, cosmopolitan young people are leaving

Many people can’t bear to be in Turkey any more. Many are also prepared to marry Europeans in order to get easier access to a visa. Cansu confirms this:

“Yes, that’s right, I’ve also heard that said around me. Mainly highly educated, cosmopolitan young people want to leave the country because they feel they are not being represented politically. Everything is becoming unbearable for them, especially the increasingly authoritarian tone of the government. Many are very pessimistic about what the future holds. It is genuinely worrying having such a divided society here.

Michelangelo describes the protests as “a game which is not only being played by Turkey”. He describes the protests as “an international phenomenon. Turkey is a very important country at the moment: Because of the war in Syria, because of the Middle East and because of immigration from the East to Europe. At the beginning the protests were definitely spontaneous but since then a worldwide mobilisation of supporters has been taking place. That sounds strange to me. For a long time no-one was interested in the country and for the past year the talk has only been about Turkey. Unfortunatley this isn’t making the conflict within the country easier.”

Later he goes back to his flat in Tarlabaşi, an area of town south of Istiklal. The shop owners in his street greet him. Colourful washing flaps in front of bay windows. If you look closely, you can see that the house is a little squint. Over a glass of Çai he says: “Sure, my name is saved somewhere in the Government and Police systems. But I am a small fish. They will leave me in peace until they may need me sometime. I have nothing to hide. The government has much more to conceal.”

Translated from „Unsere Wut ist so schwarz wie die Kohle"