Ouagadougou correspondent: no Arab spring in Burkina Faso either

Published on

Translation by:

ManxMan

ManxMan

Whilst Burkina Faso offered Muammar Gaddafi asylum on 25 August, they recognised the national transitional council in early September. August also saw the jailing of three policemen for their part in the death of student Justin Zongo in custody in February. Yet why did the country's mutinies not lead to the same dramatic changes as we are now seeing in Libya?

Everything began on 22 February when the death of Justin Zongo in police custody came to light. According to the Koudougou police the student had died of meningitis. However, his fellow students believed otherwise, convinced, in the words of one of the revolt’s leaders, that ‘he died under police torture’. A series of student protests followed in Koudougou, a famously rebellious town. These gradually spread across the country leading to protests against president Blaise Compaore. Blaise, as he is popularly known, responded with the claim that the young protesters were irresponsible and were being manipulated by the government opposition which hoped to take power for itself by force. He did however stop short of Gaddafi’s famously aggressive rhetoric and did not mention drugs. Blaise conveniently forgot his own murky rise to power in 1987, when he overthrew his ally Thomas Sankara's government in Burkina Faso, ‘the land of upright people’, as the country’s name translates.

Domino effect - or maybe not?

In March and April though, the student protests were eclipsed by mutinies within the army. The situation seemed to be heating up. In Ouagadougou, a group of soldiers unhappy rose up and freed five colleagues arrested for fighting. Observing the ease with which this liberation was achieved, other soldiers in the provinces of Burkina Faso mutinied and demanded the release of a colleague accused of rape. Yet the mutineers didn’t stop at the potentially heroic action of freeing the imprisoned; instead, they used their night-time excursions and their arms to complement their modest salaries, looting nearby shops. The lootings and prisoner liberations created a domino effect: judges went on strike against the release of prisoners, while shopkeepers and businessmen protested against the lootings, calling for compensation. Meanwhile, April saw peaceful protests across the country against the rising cost of living in the country rated by the UN as the world’s third poorest. It would have been reasonable to assume at this point that Justin Zongo’s death might be the trigger for an uprising similar to that in Tunisia sparked by the death of Mohamed Bouazizi.

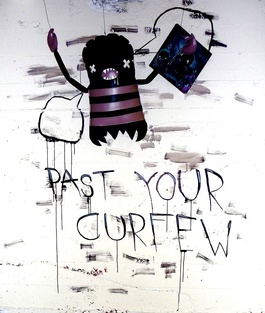

The situation in April revealed a crisis of leadership within Burkina Faso because, president Compaore aside, no leader was respected. Ignoring the announcement of a curfew and continuing to loot, the mutineers also targeted different generals and chiefs of staff as well as the mayor of Ouagadougou. Feeling powerless in the face of the absence of arrests, aggrieved traders attacked the national assembly and the headquarters of the ruling party, while Koudougou students burned down the home of recently ousted prime minister Tertius Zongo. Blaise certainly lost some confidence and dissolved his government (yes, here you ‘dissolve’ – politicians aren’t fired and don’t resign). Rumour has it that he had ‘taken refuge’. Yet while in Africa leaving the president’s chair usually means leaving power, this doesn’t seem to have happened. After a few days of calm in Ouagadougou, Blaise is now clearly in control. He even took advantage of the situation to take personal charge of the defence ministry. Perhaps this is due to Blaise’s constant battle to prevent any coherent and united opposition forming: as a result, in contrast to other Arab countries, Burkina Faso lacked a believable alternative leader.

‘How are the Burkinabés living in this far from simple situation?’ I hear you cry. It may come as a surprise that just months after numerous deaths, widespread looting and violent protests, people are living ‘normally’, more or less. The truth is that most of the troubles gave been brief or nocturnal. The rest of the time, cities are abuzz with activity and the bustle of small businesses. The maquis (as Ouagadougou bars are known) are still full of people on every corner of every road. The only difference is that people stopped talking as much about the Ivory Coast and Libya, and started talking more about the curfew. Burkinabés enjoy ‘the show’ as they say. When they were forbidden from partying and discussing politics in the maquis at night, they simply did it during the day instead. With the curfew now lifted, city streets and squares in the country are once again lively: Ouagadougou’s residents have returned to their nightly haunts without fearing the crisis’ continuation. People seem to get used to such upheavals very quickly here, just as they accept as normal the many power-cuts during the hot weather. Before taking office, former journalist and now prime minister Luc Adolphe Tiao described the only thing that all this has led to: ‘We’ve lived with this atmosphere of stability for a long time, which has made us forget certain things; such as the fact that we too can be like other countries. This crisis has shown us the reality that we are just like everyone else.’ Now let them talk about that in the maquis...

‘How are the Burkinabés living in this far from simple situation?’ I hear you cry. It may come as a surprise that just months after numerous deaths, widespread looting and violent protests, people are living ‘normally’, more or less. The truth is that most of the troubles gave been brief or nocturnal. The rest of the time, cities are abuzz with activity and the bustle of small businesses. The maquis (as Ouagadougou bars are known) are still full of people on every corner of every road. The only difference is that people stopped talking as much about the Ivory Coast and Libya, and started talking more about the curfew. Burkinabés enjoy ‘the show’ as they say. When they were forbidden from partying and discussing politics in the maquis at night, they simply did it during the day instead. With the curfew now lifted, city streets and squares in the country are once again lively: Ouagadougou’s residents have returned to their nightly haunts without fearing the crisis’ continuation. People seem to get used to such upheavals very quickly here, just as they accept as normal the many power-cuts during the hot weather. Before taking office, former journalist and now prime minister Luc Adolphe Tiao described the only thing that all this has led to: ‘We’ve lived with this atmosphere of stability for a long time, which has made us forget certain things; such as the fact that we too can be like other countries. This crisis has shown us the reality that we are just like everyone else.’ Now let them talk about that in the maquis...

Images: main (cc) benkamorvan; Blaise Compaore (cc) DaminHR; curfew (cc) liquidnight/ all courtesy of Flickr

Translated from Burkina Faso : entre rébellion et mutinerie, la vie sous couvre-feu