Orphans in Georgia: a new approach

Published on

When the Societ Union collapsed, Georgia was left with an awful legacy of harsh Soviet institutions which were supposed to 'look after' orphans, although abuse and suffering was rife. Now Georgia is striving to modernise, what is the best approach to take with the large orphan population?

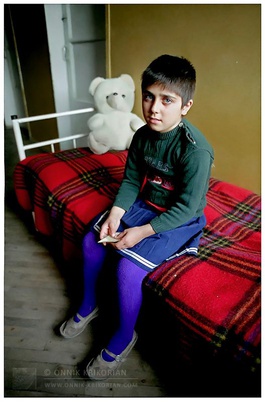

She sits in a corner, her eyes focused on the walls. She doesn’t want to talk to anyone. Her boyish haircut, severe psoriasis and occasional fits of hysteria and neurosis leave her isolated from the rest of the world. Tamari is only 13 years old. She does not know where her mother is and her father has been accused of molesting her. She and her two sisters can’t live at home anymore.

Tamari is not the only child in Georgia who is unable to live with her parents. Many children are forced to leave their homes due to poverty, domestic violence or because their parents were alcoholics, faced time in jail or just abandoned them. According to Unicef, 95 per cent of institutionalized children in Georgia are known as “social orphans”.

These children, raised in orphanages, face little opportunities and a life of poverty. Moreover, their life in these institutions leaves them without the necessary skills to find employment, and many find themselves involved in street crime, drug dealing, and prostitution. Over the years, several reports and articles have brought these dire situations to light. In order to address these issues, the government partnered with Unicef to develop a new program that aimed to close down all state orphanages and find these children new homes. Georgia ran about 72 orphanages in 2003, serving about 8, 000 orphans. According to official statistics, only three orphanages remain out of the 49 that operated in 2005. The government has made it clear that it wants to eradicate these Soviet-style institutions.

These children, raised in orphanages, face little opportunities and a life of poverty. Moreover, their life in these institutions leaves them without the necessary skills to find employment, and many find themselves involved in street crime, drug dealing, and prostitution. Over the years, several reports and articles have brought these dire situations to light. In order to address these issues, the government partnered with Unicef to develop a new program that aimed to close down all state orphanages and find these children new homes. Georgia ran about 72 orphanages in 2003, serving about 8, 000 orphans. According to official statistics, only three orphanages remain out of the 49 that operated in 2005. The government has made it clear that it wants to eradicate these Soviet-style institutions.

Therefore, in coordination with the Ministry of Labor, Health and Social Affairs of Georgia, the Charity Humanitarian Centre ‘Abkhazeti’ (CHCA) started a new project in 2011: small group homes. These homes provide an alternative to traditional orphanages and foster care. Unrelated children live in a home-like setting with either a set of foster parents or a rotating staff of trained caregivers.

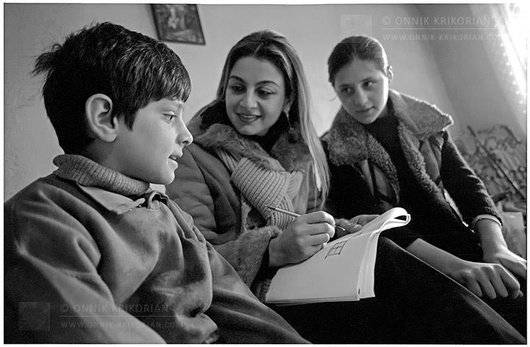

The boys and girls residing in these homes are between the ages of 6 and 18 and come from a variety of ethnic backgrounds. The homes aim to create a family style environment for the children, to support their education and development, and to provide them with the professional skills necessary for an independent life.

and 18 and come from a variety of ethnic backgrounds. The homes aim to create a family style environment for the children, to support their education and development, and to provide them with the professional skills necessary for an independent life.

In Georgia, there are three models: family-style homes for a maximum of seven children, specialized homes for a maximum of 10 children, and SOS type homes that house around seven children. CHCA runs three homes in the Kakheti region, but in total there are about 50 small group homes in Georgia and more than 10 providers: Caritas Georgia, Divine Child, Child and environment, Bres Georgia, Biliki, SOS, and others.

After having lived in CHCA’s Small Group Home for two years, Tamari is a different child. As she strokes her beautiful long brown hair, her eyes light up when you talk to her and she shows off her gorgeous smile. CHCA spent a lot of time working to improve her psychological state. Her previous aggressiveness, negative attitude and reservations have disappeared. She is able to speak about her successes at school and has several friends with whom she spends time. She is also learning how to sew, and she now has her own sewing machine. For the first time in her life, Tamari sees the future brightly.

After having lived in CHCA’s Small Group Home for two years, Tamari is a different child. As she strokes her beautiful long brown hair, her eyes light up when you talk to her and she shows off her gorgeous smile. CHCA spent a lot of time working to improve her psychological state. Her previous aggressiveness, negative attitude and reservations have disappeared. She is able to speak about her successes at school and has several friends with whom she spends time. She is also learning how to sew, and she now has her own sewing machine. For the first time in her life, Tamari sees the future brightly.

However, these small group homes are a temporary solution. Around eighty per cent of these children have at least one parent who retains parental rights but is currently unable to care for their children. Therefore, the government, in coordination with Unicef and other providers such as CHCA, launched a campaign to reunite these children with their biological parents or relatives.

As a consequence, Tamari’s life changed dramatically. After having lived in a small group home for two years, an uncle came forward. This last New Year was the first time that Tamari and her sisters did not spend in the orphanage. Instead they celebrated with loving relatives. The girls appeared to be the happiest children in the world that day.

For Privacy reasons the names in the articles have been changed.

Photos courtesey of Onnik James Krikorian. The photos do not portray CHCAs Small Group Homes, but are a collection of vulnerable children in Georgia.