Of Roma art and Charlie Chaplin

Published on

On 7 June the Venice Biennale saw the grand opening of ‘Paradise Lost’, its first Roma Pavilion. Gipsy kitsch, or the artistic emancipation of an oppressed people?

Curator Timea Junghaus huffs and puffs as she sits herself down outside a Venetian cafe – more than an hour too late – for an interview. ‘Artists!’ she offers as an excuse. She has been up most of the night helping one cope with a nervous breakdown. But artists were not her only worry when organising the first ever Roma Pavilion at the Venice Biennale - a prestigious bi-annual contemporary art exhibition. ‘At first the Biennale organisation was hesitant to have a separate, special exhibition for Roma artists. Normally pavilions are based on nationality, such as the French and the Italian Pavilions. They thought I was just one of those angry feminist minority women.’ But with a little help from friends such as Italy’s Europe Minister Emma Bonino and EU President José Manuel Durão Barroso, Junghaus won the approval of the Biennale.

Roma exist

Housed in the 16th century Palazzo Pisani, the Roma Pavilion brings together sixteen Roma artists from eight European countries, most of whom do not even share the same dialect of the Romani language, let alone the same artistic education. ‘We’re the first truly European Pavilion,’ says Junghaus proudly.

Inside the Pavilion lie paintings, videos and installations, such as a black Roma skirt stuck to the wall with knives, resembling a pinned down butterfly. ‘Despite the diversity, I do not have to look hard for similarities in the work of the artists,’ says Junghaus. ‘They all suffered serious traumas from their minority status. What their work has in common is either a form of therapy or revenge.’

It shows. Walking into the Pavilion, the first thing to greet the eye is a videoscreen, on which a young Hungarian woman can be seen who is asked if she has any problems with Roma. 'Only one,' she replies. 'That they exist.'

Not a typical gipsy

That they do. A little further away, one Roma artist is dancing to the sound of his colleagues’ clapping hands. His name is Gabi Jiménez – or François Lopez, depending on where, how and if his mum filled out official papers. As for where he comes from, he describes his past whereabouts as ‘where the wind took me, or policemen and trials put me.’

That they do. A little further away, one Roma artist is dancing to the sound of his colleagues’ clapping hands. His name is Gabi Jiménez – or François Lopez, depending on where, how and if his mum filled out official papers. As for where he comes from, he describes his past whereabouts as ‘where the wind took me, or policemen and trials put me.’

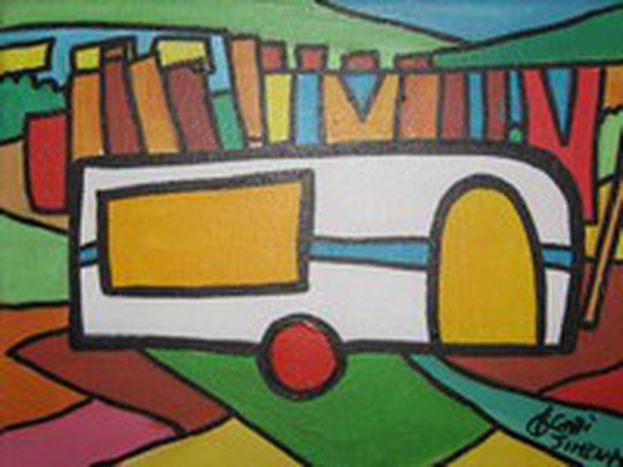

But his artwork leaves no room for doubt. 'I am definitely not a typical gipsy artist,’ says Jiménez. He gestures to his brightly coloured paintings covering the walls, showing - well, typical gipsy things such as caravans and people playing guitar. ‘No,’ he says passionately. ‘You see caravans. I see simple and recognisable images that show the positive aspects of Roma life. I show happiness, where others see only the bad side, the stereotypes. Let’s say I found out the hard way that art is a good way of waging a campaign,’ he adds with a smile, in reference to his rocky past.

‘High culture’

'I personally see the Roma Pavilion as a political statement on racism,' agrees curator Junghaus. 'But not all the artists want to participate in this statement. It might cost them commissions in their home countries. The aim of the exhibition is first of all to give Roma artists the opportunity to show to their own community and the rest of the world that Roma culture is about more than gipsy music. We are creating Roma high culture.’

'I personally see the Roma Pavilion as a political statement on racism,' agrees curator Junghaus. 'But not all the artists want to participate in this statement. It might cost them commissions in their home countries. The aim of the exhibition is first of all to give Roma artists the opportunity to show to their own community and the rest of the world that Roma culture is about more than gipsy music. We are creating Roma high culture.’

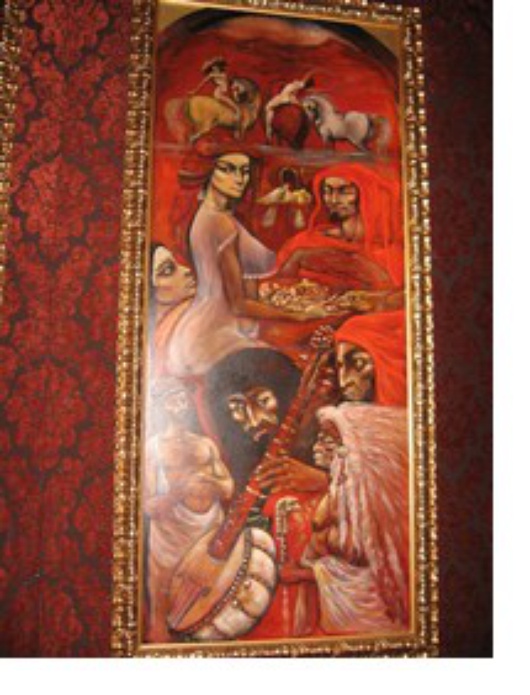

But is the Roma community itself waiting for this ‘high culture’? In one of the Palazzo’s rooms, visitors are suddenly surrounded by charging wild horses, exotic gipsy princesses and, surprisingly, Roma star Charlie Chaplin. These are the paintings of the Hungarian Roma István Szentandrássy, which Junghaus included despite fierce protests from the advocates of Roma high culture. ‘This is what pleases the Roma community itself,’ she explains. ‘This is what Roma with buying power have hanging on their walls. Roma Pride, you might call it.’ Many art critics, she concedes, would rather call it gipsy kitsch. But whatever its name, it is the one room in the Pavilion where the visitor is really transported to another world.

Stolen goods

So the Roma Pavilion tries to cater both to those who wish to see 'high culture', and those who love Roma art exactly because of its stereotypical exotic and romantic elements. Will it manage to satisfy, or disappoint both groups? The artists themselves do not seem to care too much, as they drink, dance - with one artist even vigorously popping her glass eye in and out - into the night. They even take it as a good sign that some of the Pavilion’s banners, complete with special designs from one of the artworks, on the outside of the Palazzo Pisani are stolen on its opening night – at least someone must like their artwork.

So the Roma Pavilion tries to cater both to those who wish to see 'high culture', and those who love Roma art exactly because of its stereotypical exotic and romantic elements. Will it manage to satisfy, or disappoint both groups? The artists themselves do not seem to care too much, as they drink, dance - with one artist even vigorously popping her glass eye in and out - into the night. They even take it as a good sign that some of the Pavilion’s banners, complete with special designs from one of the artworks, on the outside of the Palazzo Pisani are stolen on its opening night – at least someone must like their artwork.

Most visitors will however leave the exhibition not with stolen goods, but with more questions than answers – what is Roma art, who represents it best and should it bear a political message? But those are questions that have not been asked by the general public before. And therein may lie the success of the first ever Roma Pavilion. It shows that Roma, and Roma art, exist. Now it is up to the public to deal with it.

The Roma Pavilion is located in the Palazzo Pisani S. Marina (piano nobile), Venice, Cannaregio 6103, Calle delle Erbe. It is open to the public from 10 June until 21 November 2007