No-río: 'There must be space to criticise religious leaders'

Published on

Japan’s leading cartoonist No-río on France, freedom of press, Playboy and political cartoons

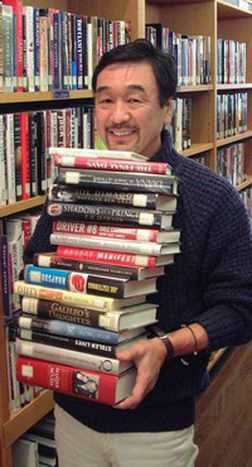

This is an unorthodox brunch. We’re 50 km from the Sea of Japan and 10 km from a volcano. It’s a dark wintry evening, and I am waiting on a storm-battered street of a provincial town. It’s here, in Hirosaki that I meet Japan’s leading political cartoonist, Norio Yamanoi. We walk to the sanctuary of a Viennese style café, our umbrellas rising up against the gale.

From Playboy to Paris

“My name No-río means ‘I don’t laugh in Spanish’”. His face breaks into a mischievous smile. A slight man with laughing eyes, he looks much younger than his 60 years. He is wearing a shemagh, a present from the Palestinian cartoonist Boukhari Baha. With every step, No-río confounds the labels that should define him. He is a curious paradox: a Japanese free spirit, vocal and easily engaged in debate, which is strange in a country where silent consensus is the norm. The Japanese rarely break from the mould, but when they do, they do it so well.

The weather merits an Irish coffee, but we opt for the more continental Viennese coffee. No-río begins. “From the age of 13, I began to read Playboy. I became interested in cartoons, mostly sexual, but more importantly the form of expression.” Smiling, he continues. “Articles we can stop reading, but cartoons we can’t; in a moment we can understand everything, they are so strong.”

Tokyo talent, Paris polemic

No-río, who studied Spanish in Tokyo during the late sixties, did not set out to become a cartoonist. “My art grade in school was very bad,” he laughs. “I thought that I had no talent in drawing.” The big year of student protest in Japan was 1969, taking the cue from Paris in ’68. During that time, No-río recalls, “I wanted to protest against society and I was looking for a medium to express myself; I chose movies, because I thought I had no talent for cartoons.”

Mozart’s fifth starts playing loudly in the café. No-río explains that he initially moved to Paris to follow his interest in film. It was a move that ultimately kick-started his cartooning career. “At that time, in France there was the Nouvelle Vague and the Cinémathèque française. There were many young people who despite having no career in movies, enjoyed big hits in France and worldwide. It was a place with a lot of opportunities for young people.”

No-río’s entry into the world of political cartooning is as much thanks to the serendipitous breaking of a toilet door as to his insightful wit. “I shared a big apartment with three young people. One day the toilet key broke, and I drew two cartoons: ‘occupied’ and ‘free’.” He takes a page of my notes to quickly sketch the images. The ‘occupied’ cartoon shows a toilet in the form of a tank, a reference to the Soviet occupation of Prague; the ‘free’ cartoon is a toilet with the statue of liberty as a cistern.

No-río developed this motif in a series of twenty cartoons. “I had a chance to show them to a Japanese cartoonist, and he told me that I should turn professional.”

'The EU can have a positive effect'

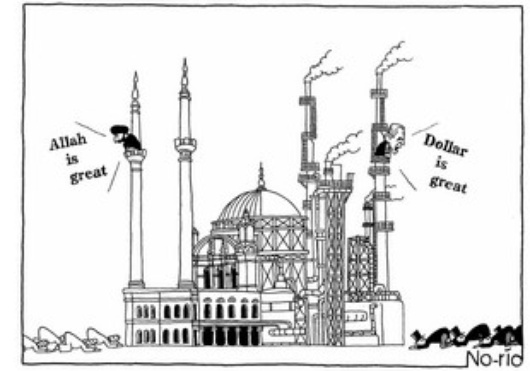

The waiter arrives with two fruit scones, whose raisins turn out to be red bean paste. We turn from scones to international relations. “In drawing cartoons, I support two things: the UN and the EU.” I am surprised. In Japan and Asia in general, the EU is not a visible entity, and when it is, it is viewed more with confusion than admiration. No-río continues, “the EU must be some kind of solution against worldwide war. Now we suffer from the conflict between Islam and Christianity, and for me, the best chance of an improvement is for the EU to accept Turkey as a member."

The waiter arrives with two fruit scones, whose raisins turn out to be red bean paste. We turn from scones to international relations. “In drawing cartoons, I support two things: the UN and the EU.” I am surprised. In Japan and Asia in general, the EU is not a visible entity, and when it is, it is viewed more with confusion than admiration. No-río continues, “the EU must be some kind of solution against worldwide war. Now we suffer from the conflict between Islam and Christianity, and for me, the best chance of an improvement is for the EU to accept Turkey as a member."

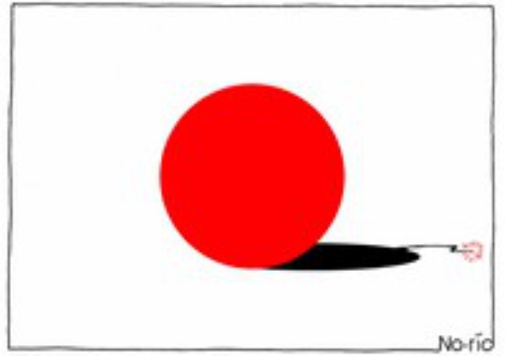

I ask No-río, who lived in France for ten years, teaching Japanese and working as a cartoonist, what he misses most about living in Europe. He pauses. “The freedom of expression. For me, it feels that there are no limits there.” It’s a powerful answer. “In Japan. it is so difficult to draw on certain topics. In my opinion, Emperor Shwa (Hirohito, father of current Emperor Akithito) had some responsibility for World War Two as leader of the Japanese army, but in Japan we can’t talk about it.”

The wind and rain drive more people into the café as No-río explains that due to the huge readership of Japan’s leading dailies, which approach 10,000,000 copies per day, papers follow a centrist line to keep sales and therefore advertising revenue high. “The press in Japan is economically too dependent to be free. I draw some cartoons which the papers will not publish. For some people, what I say is too hard, too strong, but we need some free space to talk about things. We must talk freely.”

Humanitarian role

The space that he lacks at home, No-río finds abroad. A guest at the World Economic Forum at Davos from 2003 to 2006, and a member of the recently launched UN initiative Cartooning for Peace, No-río travels for two months of the year promoting tolerance and peace through his cartoons.

The space that he lacks at home, No-río finds abroad. A guest at the World Economic Forum at Davos from 2003 to 2006, and a member of the recently launched UN initiative Cartooning for Peace, No-río travels for two months of the year promoting tolerance and peace through his cartoons.

As we finish our second cup of coffee and are going through the sixth Mozart piece, we move on to the contentious issue that thrust political cartooning onto the front pages of the world’s newspapers, the prophet Mohammed cartoons. No-río recalls his speech at the UN in October last year, where he gathered with the world’s leading editorial cartoonists to discuss their role in the world today. “As a Buddhist, I feel very free to criticise Buddhism. Buddha is very, very big and, as a cartoonist, I am very, very small, so how can I really hurt him.” He agrees that, “we must respect” other religions and customs, but they must also accept some criticism. “If there is no criticism, it’s not good.” He tilts his head and adds, “to Muslims, Allah is perfect, but religious leaders are not perfect, there must be some space to criticise them.”

I ask my final question on the role of the political cartoonist, and the howling wind seems closer. “The work of a cartoonist is based on humanism. Their daily task is to fight for peace and liberty, and against war and discrimination.” I turn off my tape recorder. He wraps his shemagh closer around his neck and shoulders, and we part with a warm handshake, before bowing and reentering the blustery Asian night.

Next week - soup in London with Magnum photojournalist Simon Wheatley