No communication, no support

Published on

Communication failures lie at the heart of problems in promoting the EU constitutional treaty. But what can be done?

One of the chief reasons for drafting the EU constitutional treaty was allegedly to address the problem of popular disengagement. The idea was that a constitution would bring the EU closer to its people by making it more ‘user-friendly’. But if France, the country that has done more than any other to create and shape the EU, can’t sell its benefits to its own citizens, who can?

The people don’t get the message

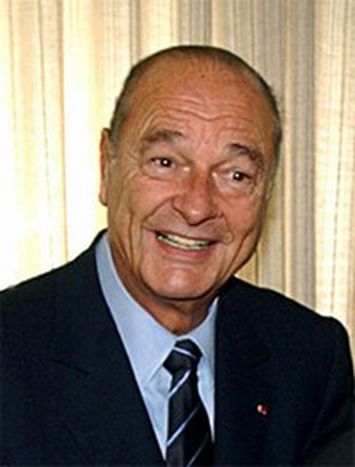

The difficulty facing President Chirac and the Yes camp in the coming French referendum is symbolic of the communications failure of both the EU institutions and national parliaments, already shown by falling turnout in European elections (less than 45 per cent last year).

The struggles of the Yes campaign are a wake-up call to the ruling elites across Europe. For too long they have taken the EU’s growing influence for granted. To Chirac’s dismay, the referendum has revealed a pent-up sense of frustration with the European Union. Indeed, Europe-wide referendums on the constitution have become the first big test of public opinion on what the EU has become and where it is heading. The French predicament has exposed the gap between lofty rhetoric and the reality that Brussels leaves Europe’s citizens cold or confused. A January Eurobarometer poll found that over 50 per cent of Europeans knew barely anything about the constitution. Worse still, a third had never even heard of it. The consequences are dangerous: clearly there is a lack of popular legitimacy at the EU’s heart.

The single market is dull

Perhaps the most striking thing about the French Yes campaign is their utter failure to convince people of the EU’s successes. Rather than talking positively about what the constitution will change, President Chirac’s main argument for the constitution has been that it is a French document and a rejection of the Anglo-Saxon liberalising agenda – the “communism of our age” as he calls it. This resort to Anglo-Saxon bashing is an admission that his mission to convince the people is failing.

So why are Europe’s own citizens so blasé or downright hostile to the virtues of the EU? First, as Mr Chirac discovered when he addressed an audience of young people in a television debate last month, the argument that the European Union has stopped the continent’s wars does not count for much with the new generation. Similarly, claims that the EU has delivered unprecedented prosperity cuts little ice with voters who live in countries saddled with high unemployment and stalling growth, like Germany and France. As Jacques Delors, an ex-President of the European Commission, once said, “people can’t fall in love with the single market”. His remark epitomises the difficulty of convincing people that complex and technocratic EU policies really do improve people’s lives. Nevertheless, it is the job of the politicians and bureaucrats to do so.

Moreover, the EU’s most recent success, the spread of democracy to countries that were until fairly recently communist states, is actually undermining the Union’s popularity in some countries, particularly France. The French No campaign has hammered home the point that the new EU member states are a threat to the French vision of a ‘social Europe’ as a result of their economic policies. Another explanation for popular antipathy to the EU is the tendency of politicians across Europe to use it for their domestic political ends. Often this has meant using Brussels bureaucrats as scapegoats to divert attention away from their own self-inflicted woes. In Britain, for example, the Labour government has been quick to lay the blame for the increasing amount of UK bureaucratic ‘red tape’ on Europe. The truth - a complex mixture of domestic and EU regulations - is lost as the Eurosceptic press love to loathe what is seen as petty interference from Brussels.

Efforts to address the communication problem

In an attempt to combat this image problem, the post of Commissioner for Institutional Relations and Communication Strategy was created last year. Margot Wallström, who was given this unenviable task of improving EU communications, advocates a radical shake-up of the Union’s strategy based on a regionalisation of EU communication policies. Wallström acknowledges that there are too many divergent messages coming from Brussels and not enough people to communicate those messages. “In many departments they do not even have a press officer”, she says. Clearly, this leaves a big space for the media to pursue their own agendas without going down the channels that they would with national political departments, who try to ‘spin’ the external message to the media. Yet, with an overall budget for EU communications of 200 million euros in 2005, should the European taxpayer not expect a more effective strategy?

Given this internal failure, it is ironic that Europe seems to have few problems selling itself to outsiders. The EU expansion last May and the growing list of countries that are desperate to join the club show that the EU conveys a positive external message as an organisation that has underpinned 50 years of prosperity, freedom, peace and stability. But even if EU voters approve the constitution, Brussels should take note that in future much more must be done to convince citizens of the EU’s benefits. If it is rejected, the constitution will become not a symbol of the EU moving closer to its people, but a damning verdict on how far apart they have grown. And Brussels and the national governments would have only themselves to blame.