Nicolai Lilin talks tattoos, Bulgarians and Transdniestria

Published on

Translation by:

Fiona Herdman Smith

Fiona Herdman Smith

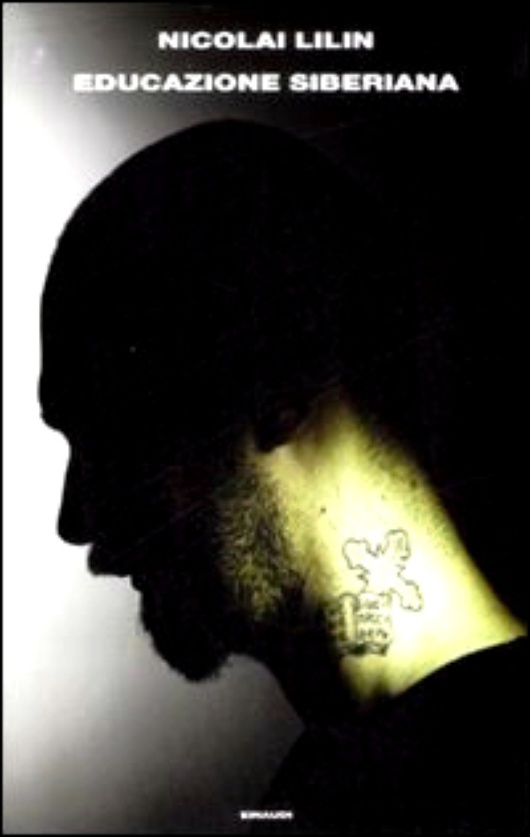

From Russia to Italy via Transdniestria. Siberian Education, the literary debut of Nicolai Lilin, tells the life story of a young man who, in spite of changing country and culture, has never forgotten the historic traditions of his original community. Interview with the 29 year-old writer and tattoo artist

Siberian Education (Einaudi, 2009) is Nicolai Lilin's debut, the tale of an adolescent growing up with the traditions of the historic Siberian criminal community, a community which managed to survive only by opposing, violently if necessary, the oppression of the communist regime which branded them 'criminals', a community which Stalin deported and isolated in Transdniestria. A Russian enclave wedged between Moldova and Ukraine, the small country of Transdniestria remains virtually unknown.

Effectively independent, having declared independence in 1990, it is still officially part of Moldova. After a very brutal period of conscription in the Russian army in Chechnya, Nicolai decided to change his life. He abandoned Russia and headed to Italy in 2003, where he was reunited with his mother. A few years ago he opened a small tattoo parlour, where he continues the ancient tradition of Siberian tattoo art, a tradition composed of rigid rules and complex codes. Interview.

Effectively independent, having declared independence in 1990, it is still officially part of Moldova. After a very brutal period of conscription in the Russian army in Chechnya, Nicolai decided to change his life. He abandoned Russia and headed to Italy in 2003, where he was reunited with his mother. A few years ago he opened a small tattoo parlour, where he continues the ancient tradition of Siberian tattoo art, a tradition composed of rigid rules and complex codes. Interview.

In your book identity is defended through adherence to community traditions. Did these traditions manage to survive Soviet socialism?

The Siberian community I grew up in actually originated from another, much older, community which had already developed a self-regulating mechanism that was opposed to any form of power. They were opposed not only to socialism but to the tsarist regime and its oppression. In my book I talk about how opposition to communism changed the community, its traditions and its social rules and how it led to its extinction. I grew up in Transdniestria, where people were forced to live by the regime. By the end of the 1980s, I already knew the community was dying. When I began to write I realised that tradition helped it to survive, but couldn't save it.

How many people make up the Siberian community in Transdniestria today?

There is no longer a community. Just me, my brother, and maybe someone else. The problem is that nothing is left in Siberia either. The heart of that community was deported to Transdniestria and it didn't survive there. The community I describe in the book was made up of forty families. You could say that tradition was a support, but in some situations it is impossible for a deracinated community to survive.

Transdniestria is an unknown country, a piece of Russia in the heart of eastern Europe. What do you think of the image of Russia in Europe?

80% of the information you get on the country is incorrect. On the one hand there's the low level of research on the part of some western journalists. On the other is Russia, an enormous country, difficult to manage. You can't sum up the reality in two words. The only thing that is certain about Russia is that it will always be deeply chaotic. That's normal. That is its historic state. In Russia a democratic government does not exist and never will. Only a dictatorship can manage to run a country like that and all the communities that live in it.

Do you consider yourself first and foremost Russian, Siberian or Italian?

I genuinely consider myself Italian in every way. I have Italian citizenship, it would be mistaken and wrong to call myself Russian. Even if recently I have been heavily criticised by my former fellow Russian citizens.

What do you think about the eastern European countries that recently joined the EU, like Romania and Bulgaria?

I have lots of Bulgarian friends and I know the situation in Bulgaria quite well. It's great to see how the EU is giving Bulgaria the chance to develop in the future. I've spoken to Bulgarian young people and they have a different mentality to Russian young people. They don't just think about making as much money as possible but also about contributing to society and developing democracy because they travel, they see the world and they see western Europe. They see what rights for young people mean, what Erasmus means, and they see how people can integrate smoothly into other countries and study and work there. In several years' time, when the new generations replace the old, then we will see complete democracy and social development.

I have lots of Bulgarian friends and I know the situation in Bulgaria quite well. It's great to see how the EU is giving Bulgaria the chance to develop in the future. I've spoken to Bulgarian young people and they have a different mentality to Russian young people. They don't just think about making as much money as possible but also about contributing to society and developing democracy because they travel, they see the world and they see western Europe. They see what rights for young people mean, what Erasmus means, and they see how people can integrate smoothly into other countries and study and work there. In several years' time, when the new generations replace the old, then we will see complete democracy and social development.

What role do tattoos play in your life? What do they have in common with literature?

The tattoo tradition I grew up with, which I am handing down and which I wear on my body, is not an exhibition but a form of communication. Like a book that people wear. A tattoo is a private thing - I hate exhibitionism, I don't show people my tattoos willingly. Writing shares many things in common with tattoos, although tattoos are much more fundamental, natural and primitive. Writing is deeper, more modern and eternal. Both things require humility and honesty on the part of their creator. Literature in particular, but also tattoos, help us feel a connection with people who are no longer with us, communicating their humane, honest messages without arrogance.

Translated from L’educazione siberiana di Nicolai Lilin