Nico Bleutge: 'Why I don't like nature poetry'

Published on

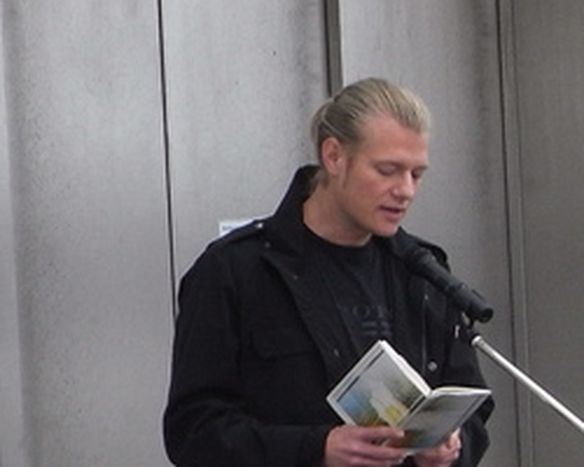

Tall, with blonde hair pulled back into a ponytail and piercing blue eyes, Nico Bleutge looks like a particularly well-groomed rugby player. One feels he ought to be more at home scoring tries than poised at the microphone of a poetry reading

I meet the poet after a reading at the beautiful yet uncanny Kempowski foundation in Nartum, a village in the north of Germany. The foundation is located in the former family home of the late German writer Walter Kempowski and we are surrounded by his collections – of books, ornaments, miniatures… Although these lend the house a somewhat surreal atmosphere – the place feels to have always been more museum than home – they reflect Kempowski’s writing, as well as the theme of the evening. Kempowski is particularly well-known for his project ‘Das Echolot’, a collage of the second world war formed through collected diaries, letters and autobiographical material. Nico Bleutge has come to read his cycle of poems ‘Drei Stimmen’ (Three Voices), which interweaves material from numerous sources, many of them from ‘Das Echolot’. With a generosity and depth of detail which is rare at poetry readings, he reads not only his poems but also a number of the works that he has drawn from. As the setting sun throws the silhouettes of the trees outside into stark relief, Nico nudges our attention to borrowed phrases, landscapes and moods.

Trying not to find one's voice

The extent of the polyphony of the poems is startling, partly because of the unbelievable amount of reading and research which has gone into each relatively short poem. More strikingly however, poetry is a game where to ‘have found one’s voice’ is often considered to be the highest possible complement – an assumption which Nico’s methods call into question. Nico considers this paradox for a moment, before explaining, ‘It can be lovely to have something like your own tone because it becomes a sort of voice which you can listen to while you’re writing. Still, it’s unbelievably difficult to get away from that tone. For me writing is something in which I try in every poem, and certainly in every book, to start again from scratch. Of course that’s impossible, but I do try to beat a new path, because otherwise I could end up always doing the same things over and over again. The writing would just get worse and I would probably get bored. You have to be challenged to a certain extent and to try out new directions once in a while.’ He breaks off and shakes his head. ‘I’ve lost the thread of it now…’ And then, as if he’s had a light bulb moment, he exclaims, ‘Working with different voices in order to work against what’s supposedly your own voice – I think that’s quite an effective method.’

Nico’s poetry could perhaps be best compared to some of Seamus Heaney’s earlier work: incorporating a web of allusions, but simultaneously conjuring up a strong sense of place and landscape. Indeed, in 2012 he was awarded the Erich Fried award for, in the words of the jury, breathing new life into nature poetry. Yet Nico himself is ambivalent about this description. He takes a deep breath and begins, ‘It’s diffic-’ before interrupting himself. ‘Well, on a very basic level I have great problems with the term nature poetry because it’s got very, very heavy connotations here in Germany. Nature poetry is connected with the fact that after the second world war, people accused poets that we had forgotten the whole evil of the war by escaping into nature, which was also of course mythologically charged and is a sort of timeless refuge, in which “I” don’t have anything more to do with the bad blood of history. I think there are a few poets who did do this kind of thing, and it simply didn’t do the term “nature poetry” any good, it damaged really damaged it. Because of that I’d probably claim the term landscape instead.’

Nico seems to work with themes – nature, history, memory – which can all be considered very political. (Nature is increasingly political nowadays with climate change becoming ever harder to ignore, while in Germany debates about memory have long been intertwined with questions of guilt.) Does he feel a sense of responsibility when dealing with such themes? He pauses. ‘I find the idea that poetry could be the vehicle for something like messages strange, but whether poetry has a…’ He breaks off, and takes a sip of water before trying to explain. ‘I think that poetry is an instrument for recognition. It can help us to understand the world and in particular to understand language. A honed relationship with language can allow us to be conscious of how linguistic expressions contain hidden ideologies, hidden histories, sometimes for example racist thoughts and ideas. A poem can make us heedful of and vigilant to the way that such hidden ideologies can be hidden in language. You know? So that is a kind of enlightening impulse, that poetry can have – making fixed expressions fluid, breaking them open and discovering new meanings.’