New World Champion Magnus Carlsen Could Change the Face of Chess

Published on

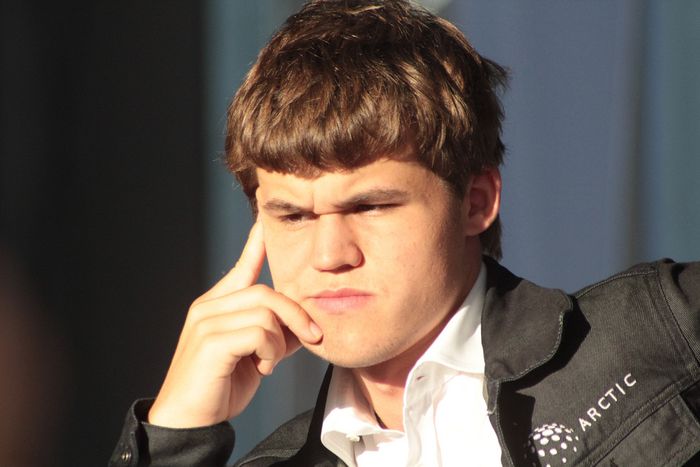

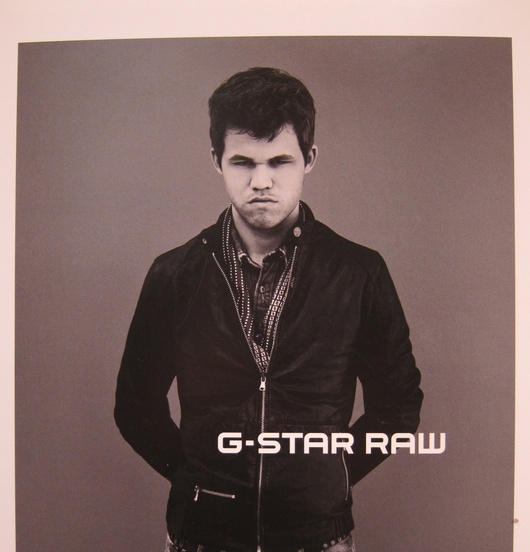

How would you imagine a typical chess world champion? Quite likely a middle-aged man from one of the former Soviet republics, wearing spectacles and an old-fashioned suit. Forget it. The face of chess today is that of new world champion Magnus Carlsen. Surprisingly, this is a face that can be found on the cover of GQ as well as in chess journals.

On Friday 22 November, eight days before his twenty-third birthday, Norwegian chess player Magnus Carlsen became chess world champion. He defeated Viswanathan Anand, twenty years his senior and playing on his home turf in the city of Chennai in the south of India. The Norwegian won three and drew seven of the ten games.

As well as maintaining his status as world number one, Carlsen works part time as a model. His looks have been compared to superstars such as Justin Bieber and Welsh football wizard Gareth Bale, not exactly what you expect from a chess grandmaster

All in good time

Carlsen’s youth has landed him many accolades. He became the youngest player ever to be ranked world number one on 1 January 2010 at the age of 19 years and 32 days. At thirteen he became the second youngest grandmaster ever after Russian Gary Kasparov, and on Friday he became the second youngest world champion. It therefore comes as a surprise to learn that Carlsen has not loved chess all his life. His father’s first attempt to spark his interest in the game failed miserably. Carlsen was five at the time and already showing signs of a phenomenal memory and dynamic problem solving ability. But the ancient game was initially of no interest. Football and skiing were more his thing.

Carlsen’s youth has landed him many accolades. He became the youngest player ever to be ranked world number one on 1 January 2010 at the age of 19 years and 32 days. At thirteen he became the second youngest grandmaster ever after Russian Gary Kasparov, and on Friday he became the second youngest world champion. It therefore comes as a surprise to learn that Carlsen has not loved chess all his life. His father’s first attempt to spark his interest in the game failed miserably. Carlsen was five at the time and already showing signs of a phenomenal memory and dynamic problem solving ability. But the ancient game was initially of no interest. Football and skiing were more his thing.

It all changed three years later. Suddenly, little Magnus was enchanted by chess. His initial motivation was very basic – to beat his elder sister. Soon he was beating much older children and then adults. When he was thirteen, he became a grandmaster and forced chess legend Garry Kasparov into a speed chess stalemate.

Everybody knew a star had been born. Lubomír Kaválek, a Czech-American grandmaster, called him the Mozart of chess because his game was not only successful but also beautiful and imaginative. British grandmaster Nigel Short praised his harmonious, versatile style that he combines with a fierce will to win.

Many different players in one

Carlsen is considered one of the most creative chess players of all times. His style of play cannot be clearly defined. Defeated world champion Viswanathan Anand said that the young Norwegian can be many different players. Carlsen does not seem to pay too much attention to openings, so nobody knows what to expect from him in the early stages of the game.

Unlike many other players, Carlsen is not obsessed with strategic and tactical preparation or computer analysis. Intuition, imagination and improvisation make him unique and often unpredictable. Middlegame is where Carlsen is really strong, applying ‘strangling pressure’, according to his former tutor, Garry Kasparov.

Computers that analyse games in real time are frequently puzzled by his moves. They can calculate zillions of possible moves but they are incapable of seeing how unexpected, unusual moves make opponents nervous, confusing them as to whether the move was a blunder or an ingenious trap.

His ability to see things differently and make unusual moves is accompanied by his unique attitude. The way he approaches chess is quite paradoxical. As a child he did not understand why people were making so much fuss about his spectacular wins in simultaneous games. Later he claimed to be more troubled by losing at Monopoly than at chess.

On the other hand, he is known to be a fierce competitor who sees the game as a kind of war. In a CBS TV documentary he admitted he enjoys watching his opponents suffer as they gaze into the eyes of inevitable defeat. Although his face is rounded and boyish, the intensity of his eyes strike fear into the heart of his opponent across the table. His habit of strolling to neighbouring chessboards between moves to check see how other games are developing may be a feature of Carlsen’s psychological warfare.

On the other hand, he is known to be a fierce competitor who sees the game as a kind of war. In a CBS TV documentary he admitted he enjoys watching his opponents suffer as they gaze into the eyes of inevitable defeat. Although his face is rounded and boyish, the intensity of his eyes strike fear into the heart of his opponent across the table. His habit of strolling to neighbouring chessboards between moves to check see how other games are developing may be a feature of Carlsen’s psychological warfare.

Grandmaster, model... and movie star?

He even did it to Kasparov when he was only thirteen, claiming that he knew what move Kasparov would make next anyway so there was no point sitting at the desk. As a child, Carlsen used to play with a football while waiting for his opponents’ moves. This could be perceived as either arrogance or a sign of genius, depending on your perspective.

Of course, having a young superstar is a gift for any sport and an opportunity for marketers. Carlsen has already modelled for a Dutch designer clothing company and has been offered a role as a chess master from a faraway galaxy in Star Trek 2. He had to turn the role down because he was unable to secure a work permit in time.

Some chess lovers hope that Carlsen’s fame will make chess popular among young people again. A centuries old game may appear obsolete in the age of sophisticated computer games, but more than 600 million people play it worldwide. Europe is a chess stronghold. It is taught at schools in several countries. Between 2010 and 2012 in the UK, for example, chess was reintroduced into 175 primary schools.

Chess is already compulsory in primary schools in Armenia. In September 2013, a subject called skill-building chess, developed by one of the greatest female players of all time, Judit Polgár, was introduced in schools in Hungary.

Youngsters like to emulate the rich and famous, even when they move black and white pieces on a wooden board. Magnus Carlsen could prove to be a breath of fresh air for the world of chess. Having appeared on the front page of GQ magazine and with his great sense of humour, it seems that Carlsen can offer the chess world a lot more than his prodigious talent alone. Perhaps he can fulfil that elusive challenge of making chess cool.