Nelson Mandela's work is not done

Published on

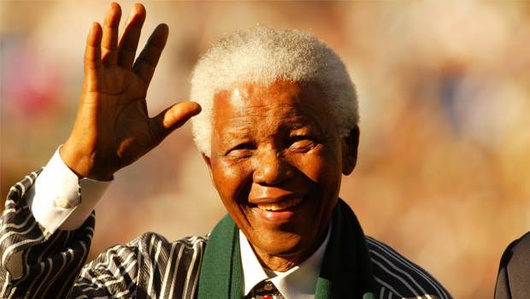

Nelson Mandela is a talisman for the progress that South Africa and indeed the world as a whole has made in regards to rights for black people. However despite the achievements of figures such as Mandela, King and Malcolm X, racism still remains an insidious force in our world.

The disparity in economic wealth between blacks and whites is vast. The simple fact remains on the balance of statistics: you are far better off being white than black in South Africa. The case is the same throughout the world; Mandela’s momentous task is certainly not finished.

In western Europe we often congratulate ourselves in regards to discrimination and racism through the lens of relativism, normally in relation to the USA. However discerning a society’s progress on discrimination through comparison is facile, especially when we decide to compare ourselves to America; a country where three quarters of white people believe racist sentiments such as ‘Blacks prefer to accept welfare’ and half believe ‘Black people are less intelligent than white people.’ People love to point to Obama as progress within the States, but what they fail to notice is that he is the ninth black senator to be appointed since the creation of the Senate in 1789. These anomalies are being used as a smokescreen to mask the lack of progress for blacks across the world.

Where are we today?

This does beg the question, how bad is racism and discrimination in the United Kingdom?

Racism in this country has come a long way since Enoch Powell’s infamous “Rivers of Blood Speech”. Mainstream media queues up to lambast Nick Griffin, the poster boy for the far right in Britain. The attitude to overt racism has been by and large positive in a de jure and de facto sense, but the real worry is the undercurrent of discriminatory sentiment boiling up in the chocolate teapot of failed multiculturalism. In the UK we propagate and encourage a surreptitious discrimination, the consequences of which are not as obvious but still very damaging.

The moulders of our society overridingly ignore ethnic minorities. Black people find themselves underrepresented in all the top professions, from politics to journalism, from teaching to the city. We often hear about lack of women in boardrooms and politics; I think we really do not hear enough about the underrepresentation of blacks in prominent positions within our societies.

The moulders of our society overridingly ignore ethnic minorities. Black people find themselves underrepresented in all the top professions, from politics to journalism, from teaching to the city. We often hear about lack of women in boardrooms and politics; I think we really do not hear enough about the underrepresentation of blacks in prominent positions within our societies.

65% of African-Caribbean children raised by one parent

These institutions see no wrong with replicating themselves in their image again and again. The problem is compounded by a lack of role models for young black men, both in public positions and at home. As many as 65% of African-Caribbean children are raised by one parent – nearly always the mother. Turn on the TV as a young black boy and you see black musicians and sportsmen galore; go to your school, your doctor, watch the news, look at politicians and overwhelmingly these people are likely to be white. Throughout my education in West London and Buckinghamshire, I was only ever taught by one black teacher.

Some argue that race is not the issue; it’s the socioeconomic situation of an individual. Black people are more likely to be poorer, less educated, do less well within education, more likely to commit crime etc. When other variables are considered, race actually plays no part in the likelihood of committing a crime.

Statistics from Russell group universities make for  interesting reading. Surely this is an area where the playing field is leveled out? Surely, despite being underrepresented at Russell Group Universities, blacks perform as well as their white counterparts after considering all other contributory factors, such as prior attainment, subject of study, age, gender, disability, etc. The opposite is true. Blacks achieve poorer grades, go into less well paid jobs and have a less well rounded university experience.

interesting reading. Surely this is an area where the playing field is leveled out? Surely, despite being underrepresented at Russell Group Universities, blacks perform as well as their white counterparts after considering all other contributory factors, such as prior attainment, subject of study, age, gender, disability, etc. The opposite is true. Blacks achieve poorer grades, go into less well paid jobs and have a less well rounded university experience.

Blacks sense the glass ceiling above them

The calibration of this problem is extremely complicated. It stems from childhood and manifests itself in the expectations of the individual. What they think society expects them to be and how they feel society treats them; in essence black people do not have the same confidence within education or their careers as their white counterparts. They sense the glass ceiling above them and make pragmatic adjustments accordingly. Research and questionnaires conducted at Russell Group universities show that blacks feel less comfortable in their educational environment even whilst at university. They are more likely to accept advice from their peers regarding work as opposed to their lecturers. Their white counterparts however do not have the same problem in accessing information from their lecturers. White students appear to have a stronger sense of entitlement to seek help from lecturers, and a greater sense of belief that such help would be both forthcoming and available.

It is unrealistic to expect these problems to be eradicated quickly, problems ingrained by years of discriminatory history. Some whites, and indeed some blacks shudder at the prospect of positive discrimination, but what they don’t realise is that whites are still the benefactors of a history and a society that has discriminated in their favour for years. Societies that are more inclusive, that are able to effectively release the potential of all their citizens are the ones that thrive. We have come a long way and we are still making progress but don’t let Madiba’s death fool you, for he would realise that there is still ground to cover until we are truly free. The struggle for equality and justice continues and we should continue to campaign for the reconfiguration and recalibration of our societies until they strike a balance that releases the potential of all our citizens.